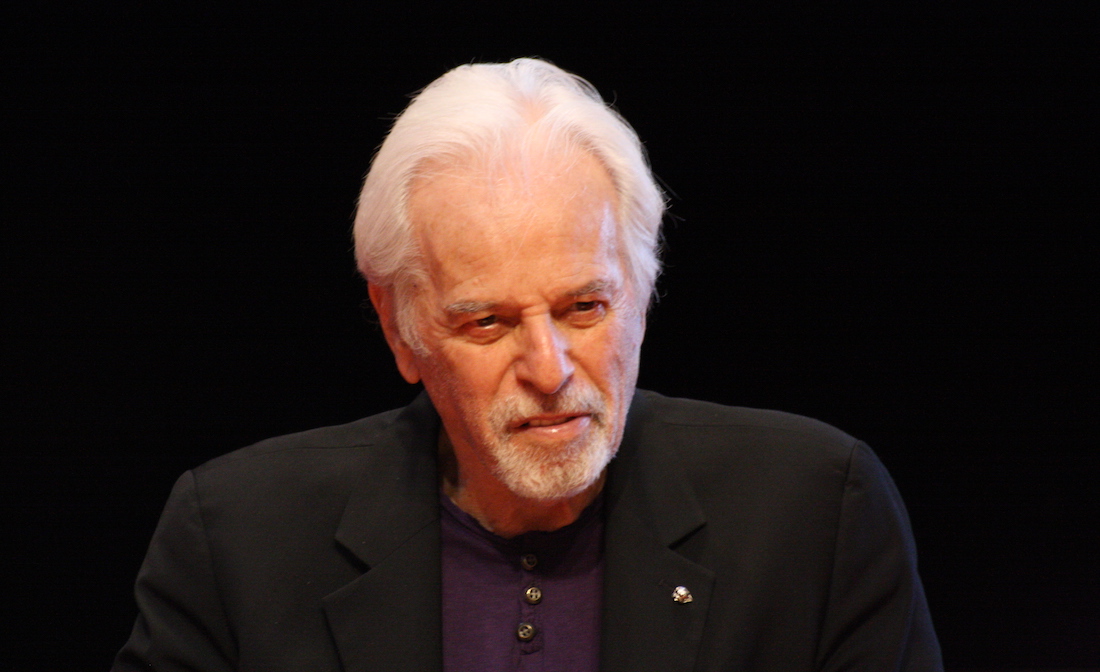

Ta-Nehisi Coates has been riding a wave so high these past few years that most honest writers would confess to at least some small degree of envy. And yet anyone—writer or reader—who appreciates Coates’ rigorous scholarship, stylistic mastery, and enthralling personal voice must also admit that the accolades are well-earned. Winner of the National Book Award for his second autobiographical work, Between the World and Me and recipient of a MacArthur “Genius Grant,” Coates is frequently called on to discuss the seemingly intractable racism in the U.S., both its long, gritty history and continuation into the present. (On top of these credentials, Coates, an unabashed comic book nerd, is now penning the revived Black Panther title for Marvel, currently the year’s best-selling comic.)

As a senior editor at The Atlantic, Coates became a national voice for black America with articles on the paradoxes of Barack Obama’s presidency and the bootstraps conservatism of Bill Cosby (published before the comedian’s prosecution). His article “The Case for Reparations,” a lengthy, historical examination of Redlining, brought him further into national prominence. So high was Coates’ profile after his second book that Toni Morrison declared him the heir to James Baldwin’s legacy, a mantle that has weighed heavily and sparked some backlash, though Coates courted the comparison himself by styling Between the World and Me after Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time. In doing so, writes Michael Eric Dyson, “Coates did a daring thing… waged a bet that the American public could absorb even more of the epistolary device, and wrote a book-length essay to his son.”

Not only did America “absorb” the device; the nation’s readers marveled at Coates’ deft mixture of existential toughness and emotional vulnerability; his intense, unsentimental take on U.S. racist animus and his moving, loving portraits of his close friends and family. As a letter from a father to his son, the book also works as a teaching tool, and Coates liberally salts his personal narrative with the sources of his own education in African American history and politics from his father and his years at Howard University. In the wake of the fame the book has brought him, he has continued what he seems to view as a public mission to educate, and interviews and discussions with the writer frequently involve digressions on his sources of information, as well as the books that move and motivate him.

So it was when Coates sat down with New York Times Magazine and ProPublica reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones at New York’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture last year. You can watch the full interview at the top of the post. During the course of the hour-long talk, Coates mentioned the books below, in the hopes, he says, that “folks who read” Between the World and Me “will read this book, and then go read a ton of other books.” He both began and ended his recommendations with Baldwin.

1. “The Fire Next Time” in Collected Essays by James Baldwin.

2. The Night of the Gun: A Reporter Investigates the Darkest Story of His Life, His Own by David Carr

3. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism by Edward E. Baptist

4. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Era of the Civil War by James McPherson

5. Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940–1960 by Arnold R. Hirsch

6. Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America by Beryl Satter

7. Confederate States of America — Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union from Avalon Project, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School

8. Showdown: Thurgood Marshall and the Supreme Court nomination That Changed America by Wil Haygood

9. American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia by Edmund S. Morgan

10. Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life by Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields

11. When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America by Paula Giddings

12. Ida: A Sword Among Lions: Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching by Paula J. Giddings

13. Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household by Thavolia Glymph

Finally, Coates references the famous debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley at Cambridge University in 1965, which you can read about and watch in full here.

via The New York Public Library

Related Content:

Toni Morrison Dispenses Writing Wisdom in 1993 Paris Review Interview

James Baldwin Bests William F. Buckley in 1965 Debate at Cambridge University

Stephen King Creates a List of 96 Books for Aspiring Writers to Read

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934

Michael Stipe Recommends 10 Books for Anyone Marooned on a Desert Island

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness