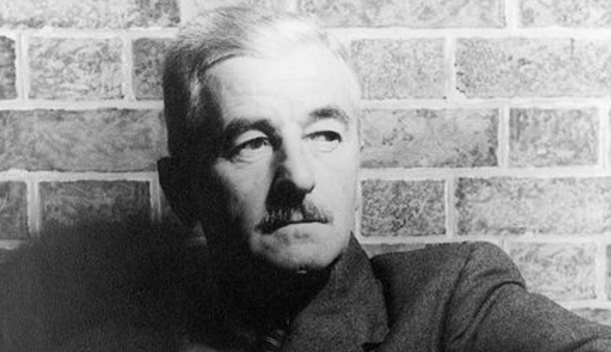

Today is the 50th anniversary of the death of William Faulkner. To mark the occasion, we bring you a 1954 recording of Faulkner reading his Nobel Prize speech from four years earlier. “I feel that this award was not made to me as a man,” Faulkner says on the tape, “but to my work–a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before.”

In classic novels like As I Lay Dying, Absalom, Absalom! and The Sound and the Fury, Faulkner created his own cosmos, combining his knowledge of the people and history of Mississippi with his gift for spinning tales. He called his cosmos Yoknapatawpha County. “I discovered,” Faulkner said in his 1956 Paris Review interview, “that my own little postage stamp of native soil was worth writing about and that I would never live long enough to exhaust it, and that by sublimating the actual into the apocryphal I would have complete liberty to use whatever talent I might have to its absolute top.”

Faulkner died at Wright’s Sanatorium in Byhalia, Mississippi in the early morning hours on July 6, 1962, which also happened to be the birthday of the great-grandfather he was named for, William Clark Falkner, the flamboyant railroad builder and novelist who was remembered as the “Old Colonel.” Faulkner had been suffering from back pain due to an earlier fall from a horse. His preferred way to deal with pain was to drink alcohol. After a binge he would typically go to the sanatorium to recover. This particular visit had seemed routine. Joseph Blotner describes the scene in Faulkner: A Biography:

The big clock ticked past midnight and July 6 came in–the Old Colonel’s birthday–with no promise of a letup in the heat. Insects thumped against the screens while electric fans hummed here and there. Faulkner had been resting quietly. A few minutes after half past one, he stirred and then sat up on the side of his bed. Before the nurse could reach him he groaned and fell over. Within minutes Dr. Wright was there, but he could not detect any pulse or heartbeat. He began external heart message. He continued it for forty-five minutes, without results. He tried mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, again with no results. There was nothing more he could do. William Faulkner was gone.

When Albert Camus died two years earlier, Faulkner was asked by La Nouvelle Revue Française to write a few words about his fallen friend. What Faulkner wrote of Camus could be his own epitaph:

When the door shut for him, he had already written on this side of it that which every artist who also carries through life with him that one same foreknowledge and hatred of death, is hoping to do: I was here.

NOTE: To follow along as Faulkner reads his Nobel address, you can find the text at the Ole Miss Faulkner on the Web site. (The page will open in a new window.) The Ole Miss page also includes a partial recording of Faulkner giving his speech in Stockholm on December 10, 1950, along with film footage of the ceremony. (Faulkner won the Nobel Prize in Literature for 1949 but it wasn’t presented until 1950, the year Bertrand Russell won the award. So Russell and Faulkner can both be seen in the film footage.) To hear more of Faulkner’s 1954 Caedmon recordings, visit Harper Audio. You can also hear over 28 hours of lectures by Faulkner at the audio archive of the University of Virginia, where he was writer-in-residence in 1957 and 1958. The archive concludes with a half-hour press conference given by the English Department faculty 50 years ago today, as they reacted to the news of Faulkner’s death.