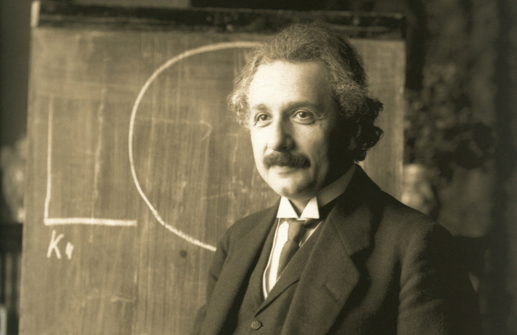

Albert Einstein endeavored to express his view of God as forthrightly as possible to a public eager to know where he stood in the popular conflict between science and religion. In 1936, a sixth-grade girl named Phyllis wrote him a letter on behalf of her Sunday School class. “We have brought up the question,” she wrote, “Do scientists pray? It began by asking whether we could believe in both science and religion.” Einstein’s reply is somewhat equivocal. He is clear enough in stating that a scientific fidelity to the “laws of nature” means that “a scientist cannot be inclined to believe that the course of events can be influenced by prayer, that is, by a supernaturally manifested wish.” This would seem to settle the question. However, he goes on to invoke the philosopher Spinoza’s god and distinguish between intellectual humility and wonder, on the one hand, and a more popular, supernatural faith on the other.

However, we must concede that our actual knowledge of these forces is imperfect, so that in the end the belief in the existence of a final, ultimate spirit rests on a kind of faith. Such belief remains widespread even with the current achievements in science.

But also, everyone who is seriously involved in the pursuit of science becomes convinced that some spirit is manifest in the laws of the universe, one that is vastly superior to that of man. In this way the pursuit of science leads to a religious feeling of a special sort, which is surely quite different from the religiosity of someone more naive.

This is probably not the response that Phyllis and her class had hoped for, and they (or their teacher) may have taken offense at the description of their faith as “naïve.” But Einstein’s careful reply also expresses a kind of scientific awe that acknowledges the limits of reason and leads to a kind of sublime feeling that can legitimately be called “religious” (much as Carl Sagan would do decades later). This, I believe, is not a casual or callous dismissal of Phyllis’s faith, something that so-called “New Atheists” are often accused of (justly or not). Instead it’s a considered response in which the great physicist shares his own version of “faith”–his faith in Nature, or the “laws of the universe,” which he concedes are “vastly superior to man.” I think it’s a moving exchange between two people who couldn’t be further apart in their understanding of the world, but who just may have found some small common ground in considering each other’s positions for a moment.

Einstein’s correspondence comes to us via the always illuminating Letters of Note

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.