For most children the word “playing” brings to mind things like wiffleball or hide-and-seek. But for a very few talented and dedicated kids it means Mozart, or Mendelssohn. Today we bring you four videos of famous violinists playing when they were incredibly young.

Itzhak Perlman, age 13: “When I came to the United States, ” Itzhak Perlman told Pia Lindstrom of The New York Times in 1996, “I appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show as a 13-year-old and I played a Mendelssohn Concerto and it sounded like a talented 13-year-old with a lot of promise. But it did not sound like a finished product.” In the clip above, Perlman plays from the third movement of Felix Mendelssohn’s Concerto in E minor during his debut Sullivan Show appearance in 1958. The young boy was an instant hit with the audience, and Sullivan invited him back. Encouraged by his sudden celebrity, Perlman’s parents decided to move from Israel to New York and enroll him in Julliard. But despite his precocity, Perlman modestly asserts that he was no child prodigy. “A child prodigy is somebody who can step up to the stage of Carnegie Hall and play with an orchestra one of the standard violin concertos with aplomb,” Perlman told Lindstrom. “I couldn’t do that! I can name you five people who could do that at the age of 10 or 11, and did. Not five, maybe three. But I couldn’t do that.”

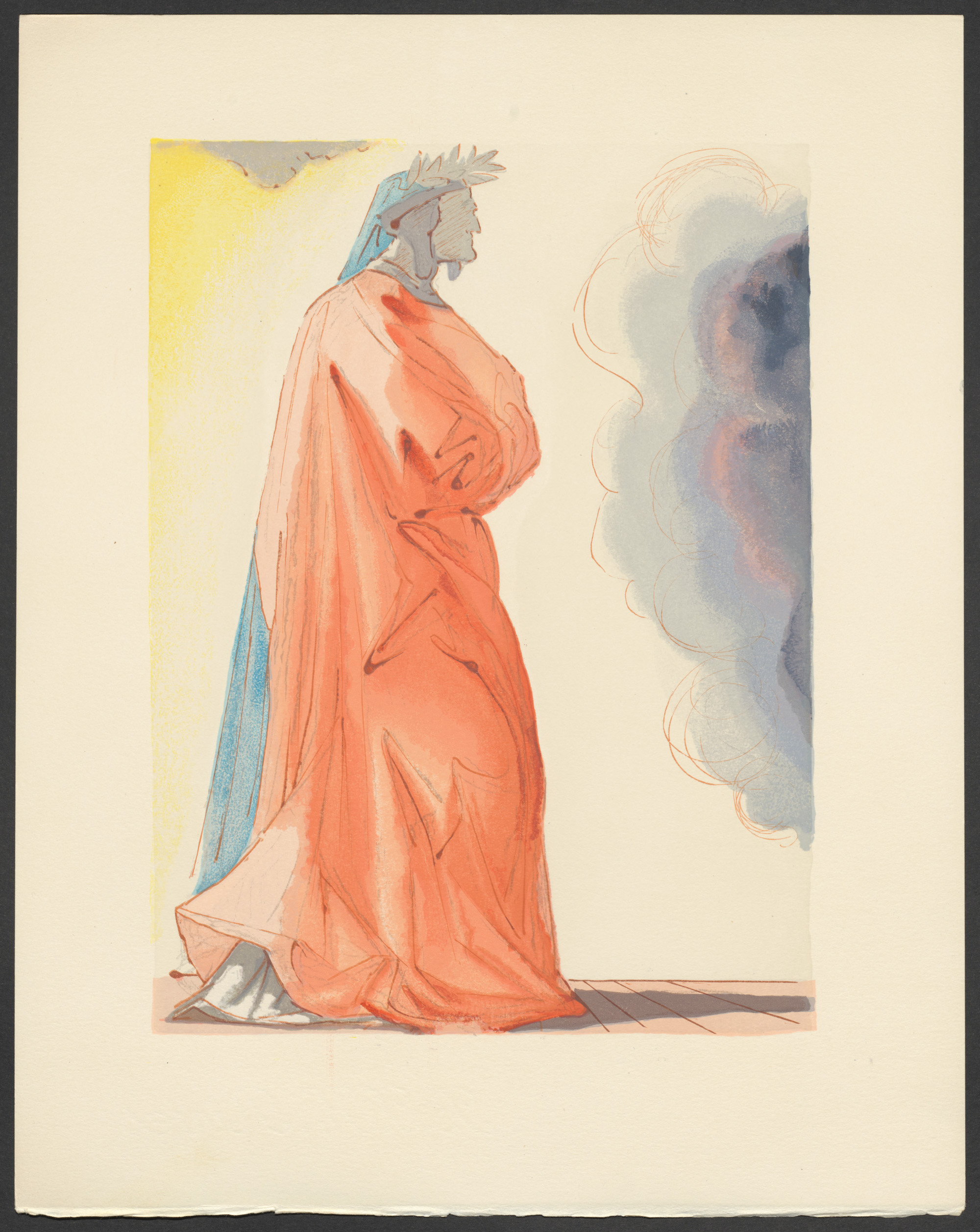

Anne-Sophie Mutter, age 13:

One violinist who certainly was able to perform at a high level at a very early age was the German virtuoso Anne-Sophie Mutter, shown here performing the Méditation from the Jules Massenet opera Thaïs with Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic in 1976, when she was 13. Mutter began playing the violin at the age of five, and by nine she was performing Mozart’s Second Violin Concerto in public. Karajan took her under his wing when she was 13, calling her “the greatest musical prodigy since the young Menuhin.”

Jascha Heifetz, age 11:

Jascha Heifetz was indisputably one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. His father, a music teacher, first put a violin into his hands when Heifetz was only two years old. He entered music school in his hometown of Vilnius, Lithuania, at the age of five, and by seven he was performing in public. At nine he entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he studied with Leopold Auer. In this very rare audio recording from November 4, 1912, an 11-year-old Heifetz performs Auer’s transcription of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Gavotte in G from the opera Idomeneo. It was made by Julius Block on a wax-cylinder Edison phonograph in Grünewald, Germany. Heifetz is accompanied by Waldemar Liachowsky on piano. At the end of the performance the young boy’s voice can be heard speaking in German. Roughly translated, he says, “I, Jascha Heifetz of Petersburg, played with Herr Block, Grünewald, Gavotte Mozart-Auer on the fourth of November, nineteen hundred and ten.” A week earlier, Heifetz made his debut appearance with the Berlin Philharmonic. In a letter of introduction to the German manager Herman Fernow, Auer said of Heifetz: “He is only eleven years old, but I assure you that this little boy is already a great violinist. I marvel at his genius, and I expect him to become world-famous and make a great career. In all my fifty years of violin teaching, I have never known such precocity.”

Joshua Bell, age 12:

The American violinist Joshua Bell began playing when he was four years old, and made his debut as a soloist with the Philadelphia Orchestra when he was 14. The video above is different from the others, in that it doesn’t present a polished performance. Instead, we watch as the legendary violin teacher Ivan Galamian conducts a lesson in 1980, when Bell was 12. Bell spent two summers studying at Galamian’s Meadowmount School of Music in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. In the video, the elderly teacher works with Bell as he plays from Pierre Rode’s Etude No. 1.