According to Freud, neurotics never know what they want, and so never know when they’ve got it. So it is with the seeker after fluent cultural literacy, who must always play catch-up to an impossible ideal. William Grimes points this out in his New York Times review of Peter Boxall’s obnoxious 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die, which “plays on every reader’s lingering sense of inadequacy. Page after page reveals a writer or a novel unread, and therefore a demerit on the great report card of one’s cultural life.” Then there are the less-ambitious periodical reminders of one’s literary insufficiency, such as The Telegraph’s “100 novels everyone should read,” The Guardian’s “The 100 greatest novels of all time: The list,” the Modern Library’s “Top 100,” and the occasional, pretentious Facebook quiz etc. based on the above.

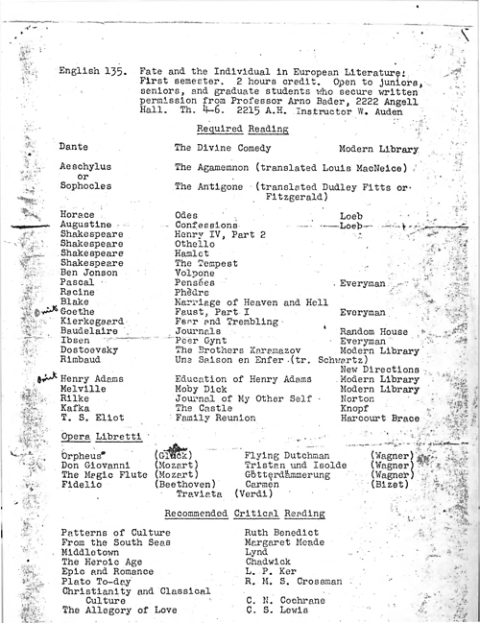

Grimes’ reference to a report card is relevant, since what we’re discussing today is the instruction in grand themes and “great books” represented by W.H. Auden’s syllabus above for his English 135, “Fate and the Individual in European Literature.” Granted, this is not an intro lit class (although I imagine that his intro class may have been punishing as well), but a course for juniors, seniors, and graduate students. Taught during the 1941–42 school year when Auden was a professor at the University of Michigan, his syllabus required over 6,000 pages of reading in just a single semester (and for only two credits!). Find all of the books at the bottom of this post.

While a few days ago we posted a syllabus David Foster Wallace created around several seeming easy reads—mass market paperbacks and such—Auden asks his students to read in a semester the literary equivalent of what many undergraduate majors cover in all four years. Four Shakespeare plays and one Ben Jonson? That was my first college Shakespeare class. All of Moby Dick? I spent over half a semester with the whale in a Melville class. And then there’s all of Dante’s Divine Comedy, a text so dense with obscure fourteenth century Italian allusions that in some editions, footnotes can take up half a page. And that’s barely a quarter of the list, not to mention the opera libretti and recommended criticism.

Was Auden a sadistic teacher or so completely out of touch with his students that he asked of them the impossible? I do not know. But Professor Lisa Goldfarb of NYU, who is writing a series of essays on Auden, thinks the syllabus reflects as much on the poet’s own preoccupations as on his students’ needs. Goldfarb writes:

“What I find fascinating about the syllabus is how much it reflects Auden’s own overlapping interests in literature across genres — drama, lyric poetry, fiction — philosophy, and music.… He also includes so many of the figures he wrote about in his own prose and those to whom he refers in his poetry…

“By including such texts across disciplines — classical and modern literature, philosophy, music, anthropology, criticism — Auden seems to have aimed to educate his students deeply and broadly.”

Such a broad education seems out of reach for many people in a lifetime, much less a single semester. Now whether or not Auden actually expected students to read everything is another matter entirely. Part of being a serious student of literature also involves learning what to read, what to skim, and what to totally BS. Maybe another way to see this class is that since Auden knew these texts so well, his course gave students the chance to hear him lecture on his own journey through European literature, to hear a poet from a privileged class and bygone age when “reading English Literature at University” meant, well, reading all of it, and nearly everything else as well (usually in original languages).

If that’s the kind of erudition certain anxious readers aspire to, then they’re sunk. Increasingly few have the leisure, and the claims on our attention are too manifold. At one time in history being fully literate meant that one read both languages—Latin and Greek. Now it no longer even means mastering only “European literature,” but all the world’s cultural productions, an impossible task even for a reader like W.H. Auden. Who could retain it all? Instead of chasing vanishing cultural ideals, I console myself with a paraphrase from the dim memory of my last reading of Moby Dick: why read widely when you can read deeply?

Find all of the books on Auden’s syllabus listed below:

Required Reading

Dante — The Divine Comedy

Aeschylus — The Agamemnon (tr. Louis MacNeice)

Sophocles — Antigone (tr. Dudley Fitts or Fitzgerald)

Horace — Odes

Augustine — Confessions

Shakespeare — Henry IV, Pt 2

Shakespeare — Othello

Shakespeare — Hamlet

Shakespeare — The Tempest

Ben Jonson — Volpone

Pascal — Pensees

Racine — Phedre

Blake — Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Goethe — Faust, Part I

Kierkegaard — Fear and Trembling

Baudelaire — Journals

Ibsen — Peer Gynt

Dostoevsky — The Brothers Karamazov

Rimbaud — A Season in Hell

Henry Adams — Education of Henry Adams

Melville — Moby Dick

Rilke — The Journal of My Other Self

Kafka — The Castle

TS Eliot — Family Reunion

OPERA LIBRETTI:

Orpheus (Gluck)

Don Giovanni (Mozart)

The Magic Flute (Mozart)

Fidelio (Beethoven)

Flying Dutchman (Wagner)

Tristan und Isolde (Wagner)

Götterdämmerung (Wagner)

Carmen (Bizet)

Traviata (Verdi)

RECOMMENDED CRITICAL READING:

Patterns of Culture — Ruth Benedict

From the South Seas — Margaret Mead

Middletown — Robert Lynd

The Heroic Age — Hector Chadwick

Epic and Romance — W.P. Ker

Plato Today — R.H.S. Crossman

Christianity and Classical Culture — C.N. Cochrane

The Allegory of Love — C.S. Lewis

Related Content:

W.H. Auden Recites His 1937 Poem, ‘As I Walked Out One Evening’

David Foster Wallace’s 1994 Syllabus: How to Teach Serious Literature with Lightweight Books

Nabokov Reads Lolita, Names the Great Books of the 20th Century

The Harvard Classics: A Free, Digital Collection

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, musician, and literary neurotic based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness