Serena Bramble, the mastermind behind this supercut writes, “Sterling Archer, the modern take-down of James Bond on Adam Reed’s cult animated show Archer, is many things,” including a book nerd, “but that last detail has always been a quirk in the show, with literary references spouted out almost as often as jokes about oral sex.” If you’ve watched the show, you may have caught the references to Chekhov, Tolkien and Orwell, just to name a few. But, in case you didn’t, Bramble’s supercut gathers them together and shows proof that Archer’s creator indeed had a “tenure as a frustrated English major.” Check it out.

Discover the Life & Work of Stanley Kubrick in a Sweeping Three-Hour Video Essay

For at least fifty years, the work of Stanley Kubrick has constituted an ideal object of study for serious cinephiles. Now that the technological democratization of the past decade has allowed some of the most serious cinephiles to become video essayists, that study has flowered into a host of mini-documentaries closely examining the techniques of all of film history’s most scrutinizable auteurs. The subfield of Kubrick-themed video essayism recently reached a new high watermark with filmmaker Cameron Beyl’s five-part, three-hour Directors Series study of the man’s life and work.

“Every living filmmaker today works under the shadow of Stanley Kubrick,” says Beyl in his narration toward the end of the series. “His roller-coaster ride of a career lasted 45 years and spanned two continents, leaving fourteen features and countless innovations in its wake.

In making his films, Kubrick ultimately wanted to change the form of cinema itself. His exploration of alternative story structures and new forms of expression resulted in several groundbreaking contributions to the development of the craft itself.”

If you want to find out much more about the nature of those groundbreaking contributions, block out the time and watch Beyl’s analyses of each period of Kubrick’s career: the time of his early independent features (Fear & Desire, Killer’s Kiss, The Killing), the Kirk Douglas years (Paths of Glory and Spartacus), the Peter Sellers comedies (Lolita and Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb), the masterworks (2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, and The Shining), and the final features (Full Metal Jacket and Eyes Wide Shut.)

The project leaves no aspect of Kubrick’s mastery unmentioned: his painstaking research habits, his much-discussed take-after-take-after-take shooting method on set, his careful method of discovering each film’s form in the editing room, his eagerness to incorporate new technology into his productions, and his finished pictures’ simultaneous embodiment and subversion of genre. It makes us ask the obvious but seemingly unanswerable question: who’s the next Stanley Kubrick? But Beyl actually has an answer, and one that has become the subject of his next series, already in progress: David Fincher. The director of The Game, Fight Club, and The Social Network has big shoes to fill — or so he’ll realize even more clearly if he watches the Kubrick series himself.

Related Content:

Signature Shots from the Films of Stanley Kubrick: One-Point Perspective

The Shining and Other Complex Stanley Kubrick Films Recut as Simple Hollywood Movies

Lost Kubrick: A Short Documentary on Stanley Kubrick’s Unfinished Films

Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Stanley Kubrick Never Made

Explore the Massive Stanley Kubrick Exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange

Terry Gilliam: The Difference Between Kubrick (Great Filmmaker) and Spielberg (Less So)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments: A Fun Primer on How to Strengthen, Not Weaken, Your Arguments

The science of argumentation can seem complicated, but in day-to-day terms, it quite often comes down to competing emotions. Political disagreements thrive on disgust and fear; we shut down our reasoning when we feel stressed or angry; and it is difficult to get opponents to hear us, whether they agree or not, if we do not exhibit any sympathy for their position, hard as that may be.

However, subjects in tests told not to feel anything about an issue before viewing media about it tend to be more supportive. They’ve had some opportunity to access higher order thinking skills and to override knee-jerk reactions. Most arguments take place in the fray—family dinners, online forum wars—but even in these cases, applying the best of our reasoning, before, during, or after, can put us in better stead. As Ali Almossawi, author of An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments (read online version here) puts it in his preface:

… formalizing one’s reasoning [can] lead to useful benefits such as clarity of thought and expression, objectivity and greater confidence. The ability to analyze arguments also help[s] provide a yardstick for knowing when to withdraw from discussions that would most likely be futile.

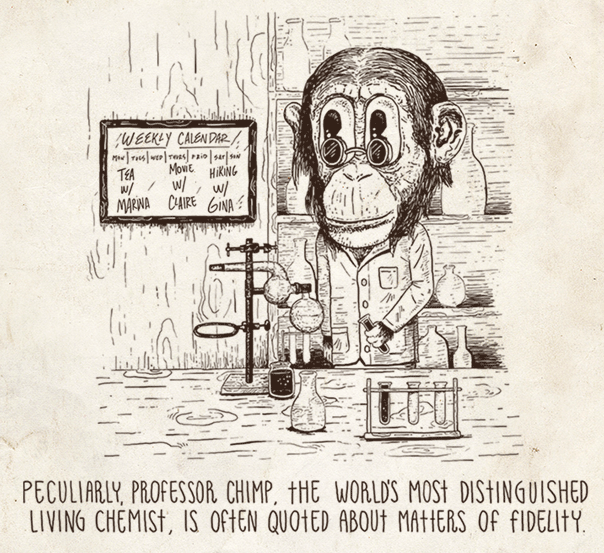

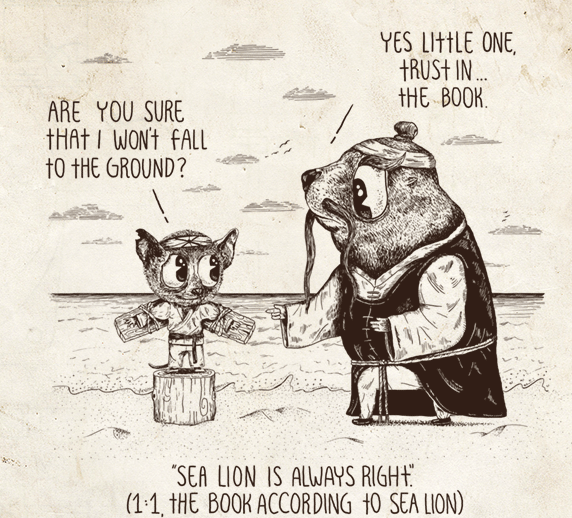

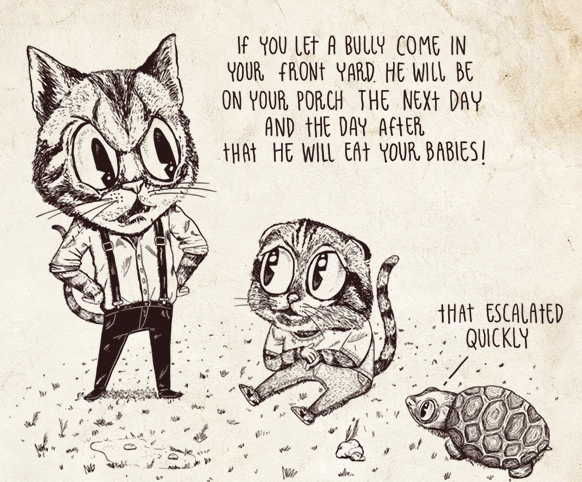

Almossawi’s strategy to mitigate bad, or wasted, thinking comes in the form of an inoculation. He quotes Stephen King, who “describes his experience of reading a particularly terrible novel as, ‘the literary equivalent of a smallpox vaccination.’” Rather than a Ciceronian treatise on what makes a good argument, Almossawi presents us with nineteen examples of the bad: informal logical fallacies we may be familiar with—Appeal to Authority (below), Circular Reasoning (further down), Slippery Slope (bottom)—as well as many we may not be.

The twist here is in Alejandro Giraldo’s playful illustrations, and the memorable examples that follow Almossawi’s descriptions. Inspired partly by “allegories such as Orwell’s Animal Farm and partly by the humorous nonsense of works such as Lewis Carroll’s stories and poems,” the drawings are also highly reminiscent, if not very much inspired by, the baroque cartoons of Tony Millionaire. The art is rich and full of surprises; the sample arguments silly but effective at making the point.

The next time you find yourself melting down over a disagreement, it will likely help to take a time out and refresh yourself with this useful primer. If nothing else, it will give you some insight into the shortcomings of your own arguments, and maybe some measure of when to drop the subject altogether. As Richard Feynman—quoted in an epilogue to the book—once remarked, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.” Find the book online here, or purchase a copy here.

Related Content:

130+ Free Online Philosophy Courses

Philosopher Daniel Dennett Presents Seven Tools For Critical Thinking

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

What Ignited Richard Feynman’s Love of Science Revealed in an Animated Video

The Experimenters, a three-episode series that animates the words of scientific innovators, concludes with the reflections of Richard Feynman, the charismatic, Nobel-Prize winning physicist who did so much to make science engaging to a broader public. Feynman knew how to popularize science — to make the process of scientific discovery and exploration so contagious — because he learned from a good teacher: his father. You can learn more about that by watching the animated video above. And don’t miss the previous two episodes in The Experimenters series. They touched on the life and thought of Buckminster Fuller and Jane Goodall.

Related Content:

Richard Feynman Presents Quantum Electrodynamics for the NonScientist

George R. R. Martin Puts Online a New Chapter from His Highly Anticipated Book, The Winds of Winter

Image created by Yulia Nikolaeva

Just a very quick heads up: Late last week, George R. R. Martin published on his web site a new chapter from his upcoming book, The Winds of Winter. The chapter tells us about Alyne (depicted above) and it contains a few spoilers. Read it here.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Google Plus and LinkedIn and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox.

Do You See Marilyn Monroe or Albert Einstein in This Photo? An Amazing Eye Test Based on MIT Research

This visual curiosity beats the black/gold dress craze of last month. The video above asks you to look at a photo and decide whether you see Albert Einstein or Marilyn Monroe — two 20th century icons who look pretty much nothing alike. If you say Albert, your eyes are in good shape. If you say Marilyn, it’s apparently time to pay a visit to the optometrist.

The science discussed here is based on the research of Aude Oliva, who works on Computational Perception and Cognition at MIT. You can see the original “Marylin Einstein” hybrid image above, which Aude created for the March 31st 2007 issue of New Scientist magazine. More background info on hybrid images can be found on this MIT page. Plus find a gallery of hybrid images here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe’s Library: How Many Have You Read?

Albert Einstein Reads ‘The Common Language of Science’ (1941)

Listen to Bill Murray Lead a Guided Meditation on How It Feels to Be Bill Murray

Photo by Gage Skidmore, via Wikimedia Commons

How does it feel to be Bill Murray?

Wonderful, presumably. You’re wealthy, well respected, and highly sought. Your random real world cameos bring joy to scores of unsuspecting mortals.

Murray’s St. Vincent director Ted Melfi cites his ability to inhabit the present moment:

He doesn’t care about what just happened. He doesn’t think about what’s going to happen. He doesn’t even book round-trip tickets. Bill buys one-ways and then decides when he wants to go home.

A stunningly good use of wealth and power. If he were anyone but the inimitable Bill Murray, I bet we’d be seething with envious class rage.

He devises the rules by which he plays, from the way he rubs shoulders with the common man to the toll free number that serves as his agent to indulging in creative acts of rebellion that could get a younger, less nuanced star labelled bratty, if not mentally ill, and desperately in need of rehab.

As if Murray needs anyone else to determine when he needs a break. When his 1984 film adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s The Razor’s Edge failed at the box office, he granted himself a four year sabbatical. He studied history and philosophy at the Sorbonne, became fascinated with the Greco-Armenian mystic George Gurdjeff…and learned how to avoid spooking the public by putting a light spin on a clearly transformative experience:

I’ve retired a couple of times. It’s great, because you can just say, “Oh, I’m sorry. I’m retired.” And people will actually believe that you’ve retired. There are nutters out there that will go, “Oh, okay!” and then leave you alone.

But how does it really feel to be Bill Murray?

…someone told me some secrets early on about living, and that you just have to remind yourself … you can do the very best you can when you’re very very relaxed. No matter what it is, whatever your job is, the more relaxed you are the better you are. That’s sort of why I got into acting. I realized the more fun I had the better I did it and I thought, that’s a job I can be proud of. If I had to go to work and no matter what my condition, no matter what my mood is, no matter how I feel … if I can relax myself and enjoy what I’m doing and have fun with it, I can do my job really well. It has changed my life, learning that.

When the question was put to him at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival, Murray led a guided meditation, below, to help the audience get a feel for what it feels like to be as relaxed and in the moment as Bill Murray. Putting all joking to the side, he shares his formula as sincerely as Mr. Rogers addressing his young television audience. Don’t forget that this is a man who read the poetry of Emily Dickinson to a roomful of rapt construction workers with a straight and confident face. Complete text is below.

Let’s all ask ourselves that question right now: What does it feel like to be you? What does it feel like to be you? Yeah. It feels good to be you, doesn’t it? It feels good, because there’s one thing that you are — you’re the only one that’s you, right?

So you’re the only one that’s you, and we get confused sometimes — or I do, I think everyone does — you try to compete. You think, damn it, someone else is trying to be me. Someone else is trying to be me. But I don’t have to armor myself against those people; I don’t have to armor myself against that idea if I can really just relax and feel content in this way and this regard.

If I can just feel… Just think now: How much do you weigh? This is a thing I like to do with myself when I get lost and I get feeling funny. How much do you weigh? Think about how much each person here weighs and try to feel that weight in your seat right now, in your bottom right now. Parts in your feet and parts in your bum. Just try to feel your own weight, in your own seat, in your own feet. Okay? So if you can feel that weight in your body, if you can come back into the most personal identification, a very personal identification, which is: I am. This is me now. Here I am, right now. This is me now. Then you don’t feel like you have to leave, and be over there, or look over there. You don’t feel like you have to rush off and be somewhere. There’s just a wonderful sense of well-being that begins to circulate up and down, from your top to your bottom. Up and down from your top to your spine. And you feel something that makes you almost want to smile, that makes you want to feel good, that makes you want to feel like you could embrace yourself.

So, what’s it like to be me? You can ask yourself, “What’s it like to be me?” You know, the only way we’ll ever know what it’s like to be you is if you work your best at being you as often as you can, and keep reminding yourself: That’s where home is.

Related Content:

Bill Murray Reads Great Poetry by Billy Collins, Cole Porter, and Sarah Manguso

Bill Murray Gives a Delightful Dramatic Reading of Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (1996)

Bill Murray Sings the Poetry of Bob Dylan: Shelter From the Storm

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Watch Stars Read Classic Children’s Books: Betty White, James Earl Jones, Rita Moreno & Many More

As if we needed the competition—am I right, parents?—of some very excellent children’s books read by some beloved stars of stage and screen, and even a former vice president. With Storyline Online, the SAG Foundation, charitable arm of the Screen Actor’s Guild, has brought together top talent for enthusiastic readings of books like William Steig’s Brave Irene, read by Al Gore, Satoshi Kitamura’s Me and My Cat, read by Elijah Wood, and Patricia Polacco’s Thank You, Mr. Falker, read by the fantastic Jane Kaczmarek. There are so many readings (28 total), I could go on… so I will. How about Betty White’s irresistible reading of Harry the Dirty Dog, just above? Or Rita Moreno reading of I Need My Monster, below, a lighthearted story about our need for darkness? Or James Earl Jones, who touchingly discusses his own childhood struggles with reading aloud, and tells the story of To Be a Drum, further down?

I won’t be able to resist showing these to my three-year-old, and if she prefers the readings of highly acclaimed actors over mine, well, I can’t say I blame her. Each video features not only the faces and voices of the actors, but also some fine animation of each storybook’s art. The purpose of the project, writes the SAG Foundation, is to “strengthen comprehension and verbal and written skills for English-language learners worldwide.” To that end, “Storyline Online is available online 24 hours a day for children, parents, and educators” with “supplemental curriculum developed by a literacy specialist.” The phrase “English-language learners” should not make you think this program is only geared toward non-native speakers. Young children in English speaking countries are still only learning the language, and there’s no better way for them than to read and be read to.

As a matter of fact, we’re all still learning—as James Earl Jones says, we need to practice, no matter how old we are: practice tuning our ears to the sounds of well-turned phrases and appreciating the delight of a story—about a dirty dog, a monster, cat, cow, or lion—unfolding. So go on, don’t worry if you don’t have children, or if they happen to be elsewhere at the moment. Don’t deny yourself the pleasure of hearing Robert Guillaume read Chih-Yuan Chen’s Guji Guji, or Annette Bening read Avi Slodovnick’s The Tooth, or… alright, just go see the full list of books and readers here… or see Storytime Online’s Youtube page for access to the full archive of videos.

Related Content:

The International Children’s Digital Library Offers Free eBooks for Kids in Over 40 Languages

Stephen Fry Reads You Have To F**king Eat, the New Mock Children’s Book by Adam Mansbach

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness