Studio Ghibli fans are still pondering the meaning of Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron, which came out last year. Though by some measure the studio’s most lavish feature yet — not least by the measure of it being the most expensive film yet produced in Japan — it’s also the one least amenable to simple interpretation. Even more so than in his previous work, Miyazaki seems to have intended to make a movie less to be explained than to be experienced. Just as the titular young protagonist descends into a bizarre but captivating underworld and returns, changed, to reality, so does the viewer.

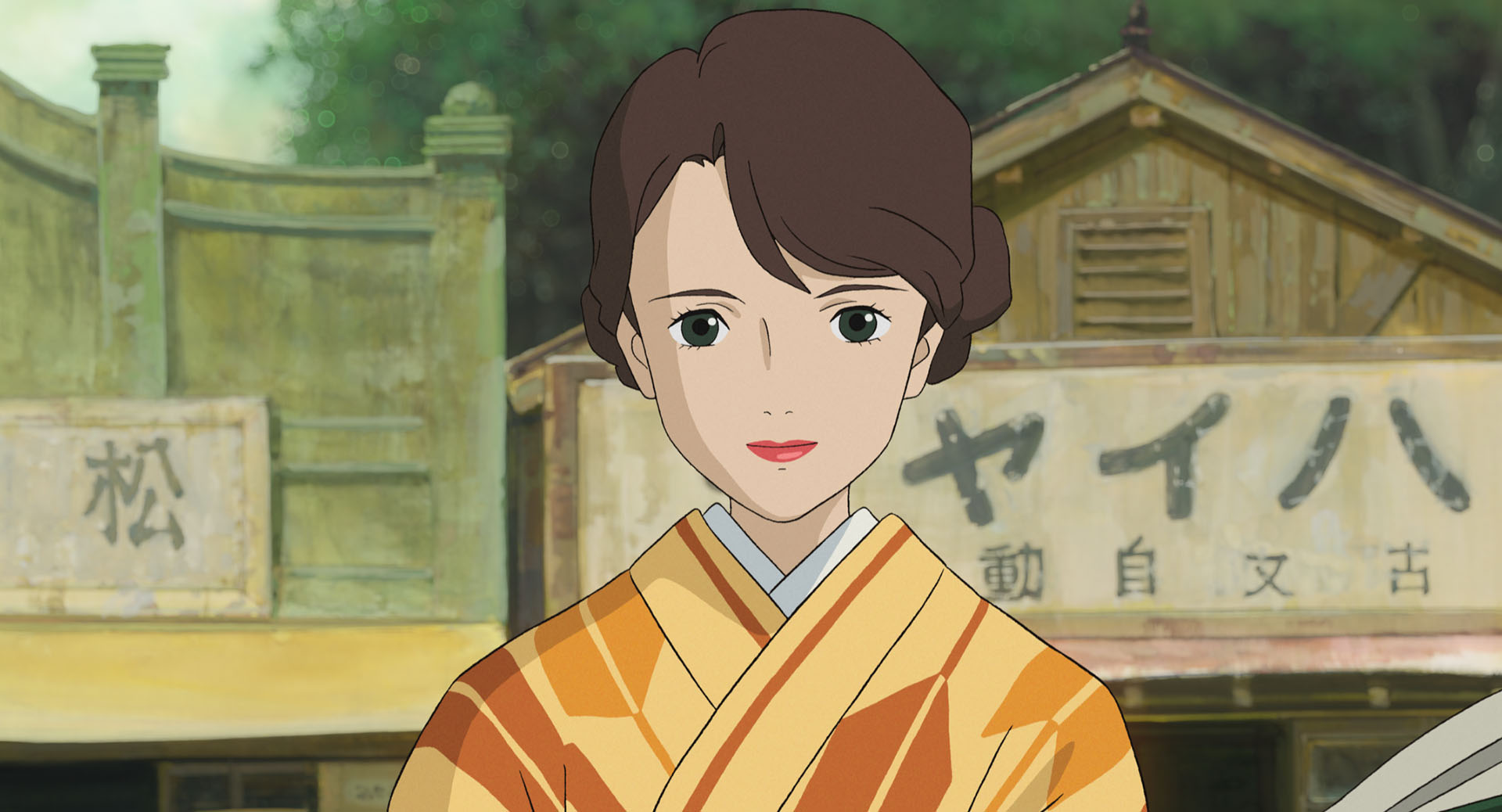

If you’ve seen The Boy and the Heron, hearing its very title (which in Japan is 君たちはどう生きるか, or How Do You Live?) will bring back to mind a host of vivid images: the roving back of bulbous-featured grannies obsessed with non-perishable foodstuffs; the posturing of the middle-age Birdman, stuffed into his avian flight suit; the pyrotechnic feats of the young Lady Himi; and above all, perhaps, the floating cascades of Warawara, those adorably round spirits who — in painstaking Ghibli fashion — appear to have been animated individually, each with its own personality. Now, you can download stills from these and other scenes at Studio Ghibli’s official web site.

These come as an expansion to Ghibli’s existing collection, previously featured here on Open Culture, of free-to-download images from their library of titles. They’re offered, the site explains, “solely for personal use by individual fans to further enjoy Studio Ghibli films.” And indeed, they may have no effect stronger than making you want to watch The Boy and the Heron again, the more deeply to feel what Miyazaki intended with his “final” picture. Not that the latest of his retirements has stuck: last fall, Ghibli president Toshio Suzuki reported that the octogenarian Miyazaki was back in the office, planning his next film. If he has more realms yet to explore, animation-lovers around the world will surely follow him. Find the images from The Boy and the Heron here.

via My Modern Met

Related content:

Studio Ghibli Producer Toshio Suzuki Teaches You How to Draw Totoro in Two Minutes

Software Used by Hayao Miyazaki’s Animation Studio Becomes Open Source & Free to Download

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.