In my childhood, I heard stories about Henrietta Lacks’ miraculous cells. I heard these stories because she happened to have been my grandmother’s cousin. But this was just oral lore, I thought at first, legendary and implausible. Cells don’t just keep growing indefinitely. Nothing is immortal. That’s a safe assumption in most every other case, but millions of people now know what only a relatively self-contained community of researchers, doctors, biology students, and, eventually, the Lacks family once did: Henrietta’s cervical cancer cells continued to grow and multiply after her death in 1951. They may, indeed, do so forever.

The once anonymous cell line, called HeLa, has provided researchers worldwide with invaluable medical data. Henrietta herself went unrecognized and unremembered until fairly recently. That all changed after Rebecca Skloot’s book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, based on an earlier series of articles, appeared in 2010 to great acclaim. Since the publication of Skloot’s bestseller, the story of Henrietta and the Lacks family has further achieved renown in a 2017 film version starring Oprah Winfrey.

Suffice it say, seeing Henrietta arrive on the pop cultural stage has been a strange experience. (One made even weirder by other media moments, like indie band Yeasayer and former Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra releasing songs about her and her cells.) The injustices of Henrietta’s story are now well-known. She was poor and received substandard medical treatment. Her cells were harvested without her knowledge, and after her death, no one notified the family about the worldwide use of her cells for biomedical research. That is, until doctors did research on her children in the 70s, publishing family medical records without consent and gathering more data because the HeLa cells had contaminated other cell lines.

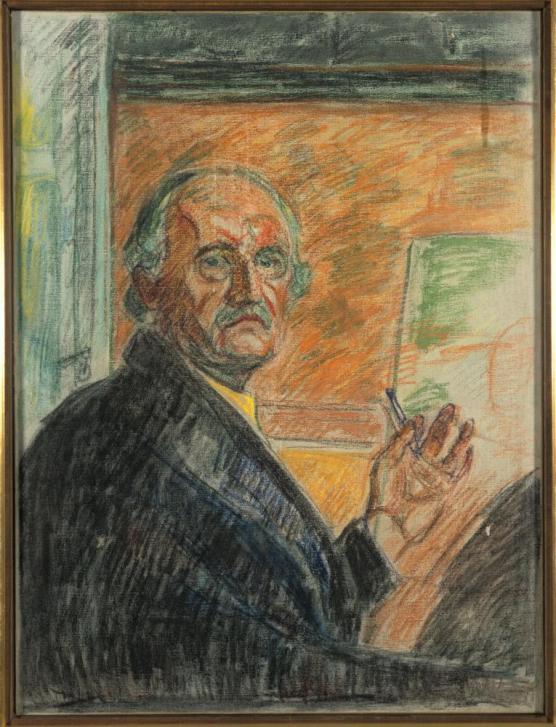

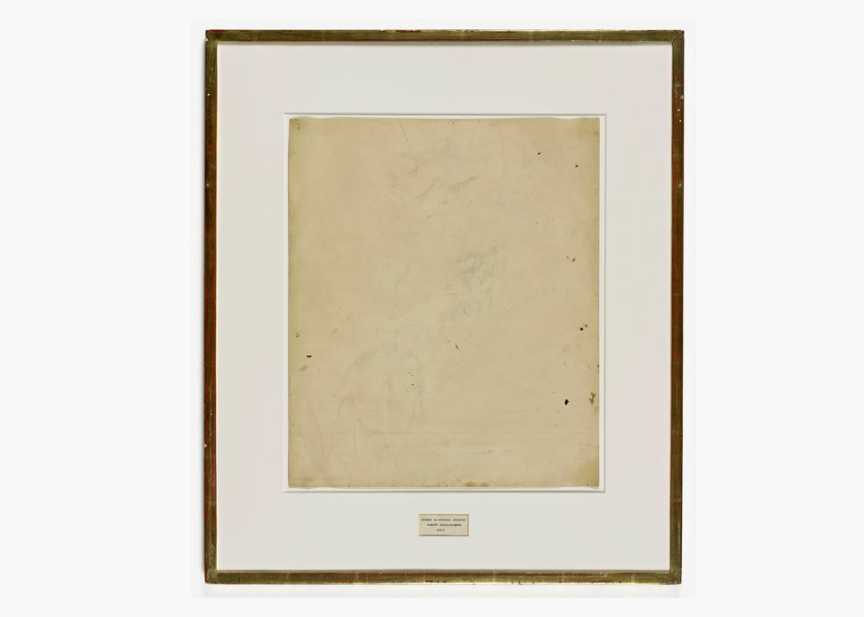

She has “become one of the most powerful symbols for informed consent in the history of science,” Nela Ulaby writes at NPR. She is also a symbol, says Bill Pretzer, senior curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), “that history can be remade, re-remembered.” To that end, Henrietta has been immortalized as a whole human being, not just the source of extraordinarily immortal cells. Her portrait, by African-American artist Kadir Nelson, now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, a representation of both the historical figure and her world-historical biological legacy.

Drawing on the photograph that adorns the cover of Skloot’s book, the portrait shows her “just like they said she was in life,” says her granddaughter Jeri Lacks-Whye, “happy, outgoing, giving,” and stylishly dressed. The two missing buttons on her dress represent the cells taken from her body, and the pattern behind her, which “almost looks like wallpaper,” says National Portrait Gallery curator Dorothy Moss, is “actually representative of her cells.” Other tributes, notes Ulaby, include a “high school for students interested in medicine” and “a minor planet whirling in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.” The cells have also generated billions of dollars in profit.

In life, she could never have imagined this strange kind of fame and fortune. The HeLa cells were instrumental in the development of the polio vaccine and research in cloning, gene mapping, and in vitro fertilization. They have traveled into space and around the world hundreds of times. The story of the person they came from, says Skloot in a 2010 interview, reminds us that “there are human beings behind every biological sample used in the laboratory… but they’re usually left out of the equation.” Making those lives an essential part of the conversation in medical research can help keep that research ethically honest, equitable, and, one hopes, based in serving human needs over corporate greed.

The portrait will remain at the National Portrait Gallery until November 4th, after which it will return to the NMAAHC.

Related Content:

Free Online Biology Courses

African-American History: Modern Freedom Struggle (A Free Course from Stanford)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness