In the introduction to her book Broad Strokes, writer and art history scholar Bridget Quinn describes her discovery of Lee Krasner, accomplished abstract expressionist painter who just happened to have been married to Jackson Pollock. That biographical detail warranted Krasner a footnote, but little more, in the art books Quinn studied in college. Learning of Krasner sent Quinn on a quest to find other women left behind by art history. “My fixation with these artists went beyond feminism,” she writes, “if it had anything to do with it at all. I identified with these painters and sculptors the way my friends identified with Joy Division or The Clash or Hüsker Dü.”

Much has changed since 1987, when Quinn’s fandom began, but Krasner is still one of the few female artists to have ever had a retrospective show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. And one artist every student of art history should know, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, remains almost completely obscure. What’s so important about von Freytag-Loringhoven? She was a pioneering Dada artist and poet—well-known in the 1910s and 20s. “Her work was championed by Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound,” writes John Higgs at the Independent (she appears in Pound’s Canto XCV). She “is now recognized as the first American Dada artist, but it might be equally true to say she was the first New York punk, 60 years too early.”

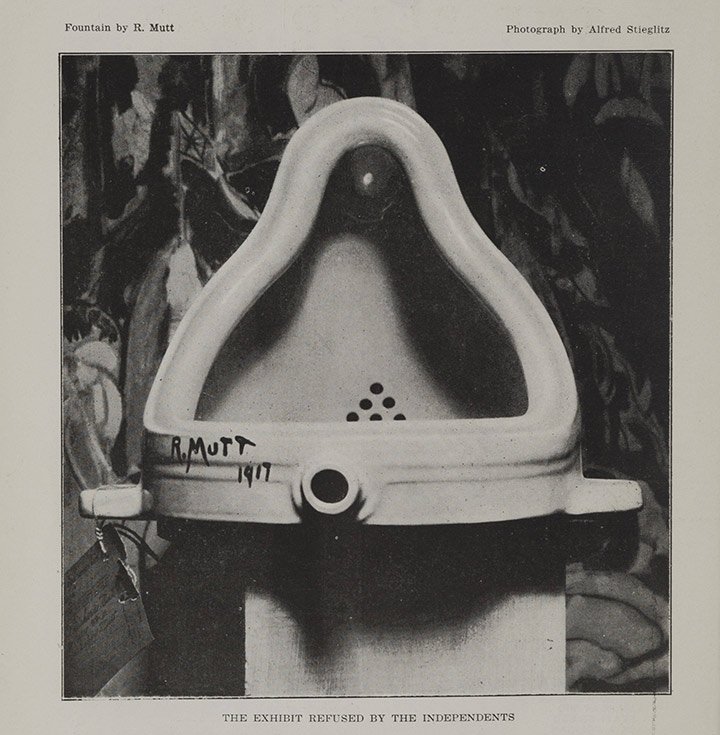

Von Freytag-Loringhoven also deserves the credit, it seems, for one of the most groundbreaking art objects to ever appear in a gallery: Fountain, the urinal signed “R. Mutt” that Marcel Duchamp claimed as his own and which has made him a legend in the history of art. The story, I imagine, might seem depressingly familiar to every woman who has ever had a male boss publish her work with his name on it. Even more frustratingly, the “glaring truth has been known for some time in the art world,” according to the blog of art magazine See All This. Yet, “each time it has to be acknowledged, it is met with indifference and silence.”

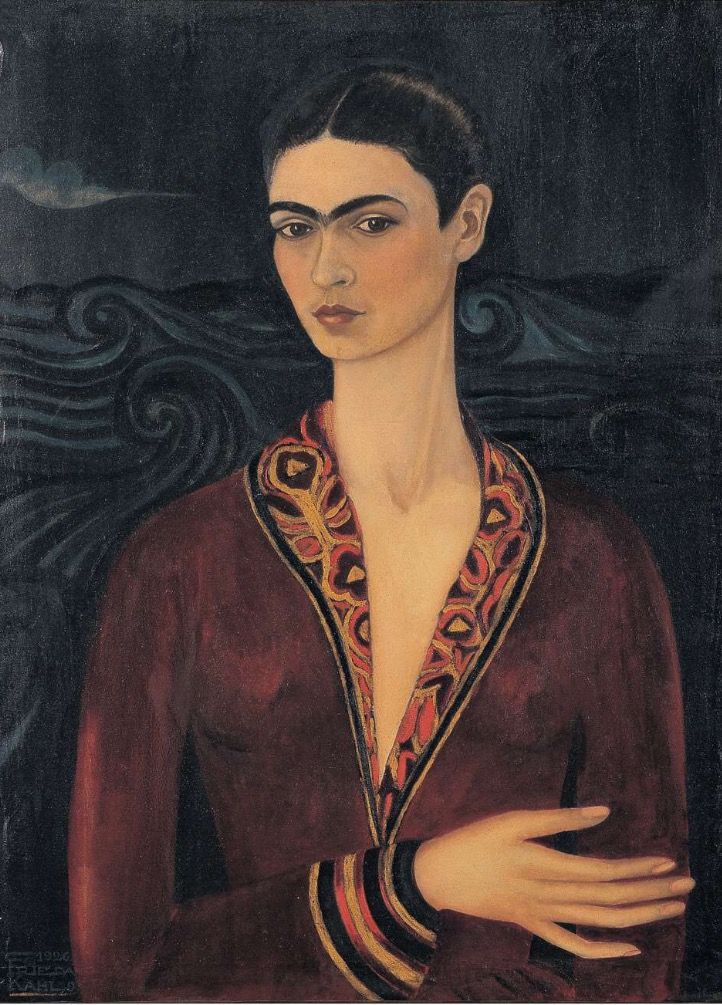

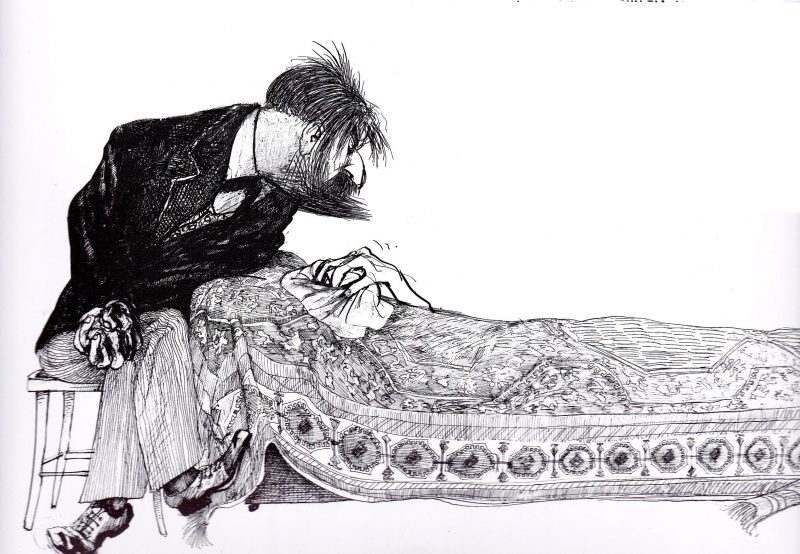

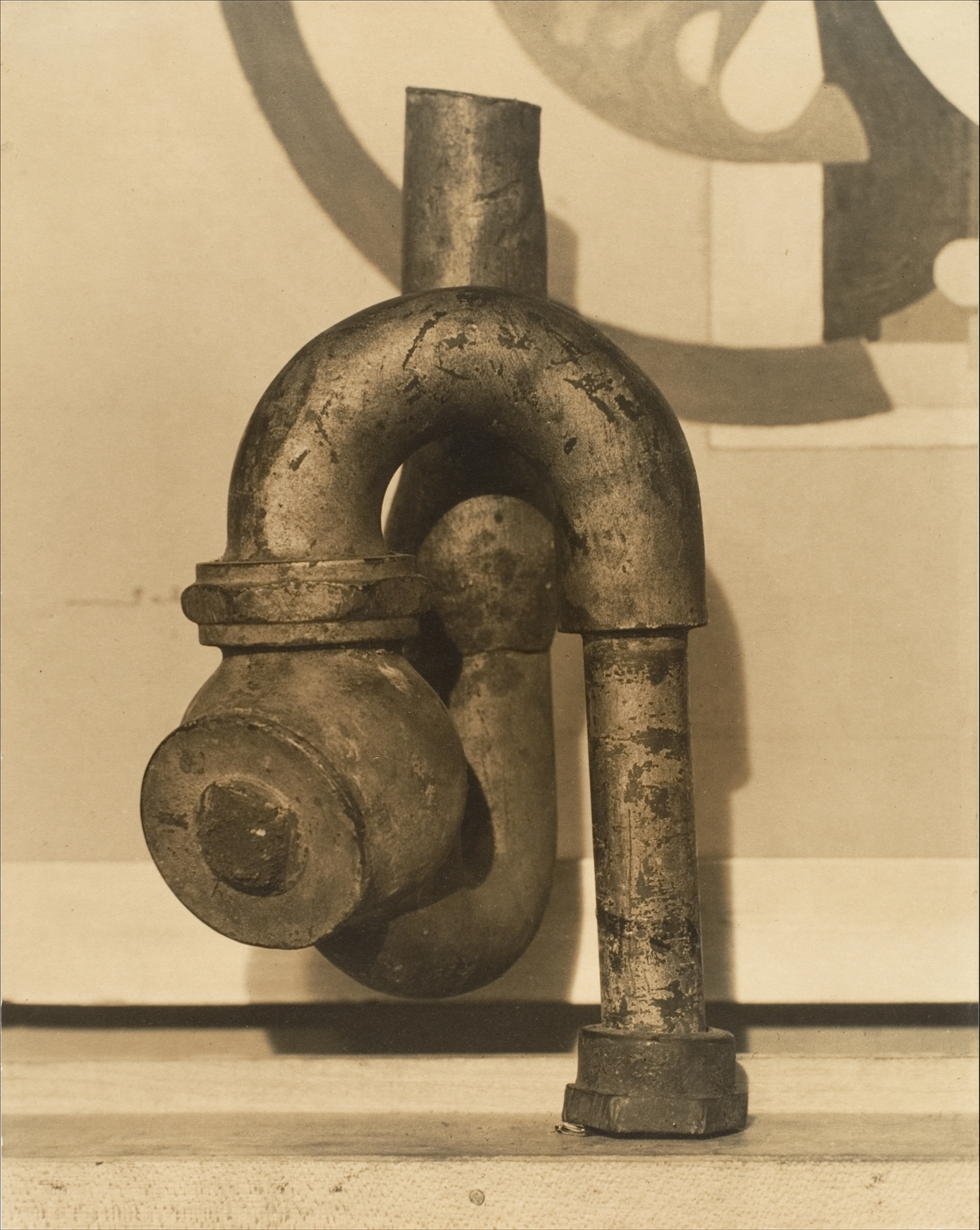

The truth first emerged in a letter from Duchamp to his sister—discovered in 1982 and dated April 11th, 1917, a few days before the exhibit in which Fountain first appeared—in which he “wrote that a female friend using a male alias had sent it in for the New York exhibition.” The name, “Richard Mutt,” was a pseudonym chosen by Freytag-Loringhoven, who was living in Philadelphia at the time and whom Duchamp knew well, once pronouncing that “she is not a Futurist. She is the future.” (See her Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, above, in a 1920 photograph by Charles Sheeler.)

Why did she never claim Fountain as her own? “She never had the chance,” notes See All This. The urinal was rejected by the exhibition organizers (Duchamp resigned from their board in protest), and it was probably, subsequently thrown away; nothing remained but a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz. Von Freytag-Loringhoven died ten years later in 1927.

It was only in 1935 that surrealist André Breton brought attention back to Fountain, attributing it to Duchamp, who accepted authorship and began to commission replicas. The 1917 piece “was destined to become one of the most iconic works of modern art. In 2004, some five hundred artists and art experts heralded Fountain as the most influential piece of modern art, even leaving Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon behind.”

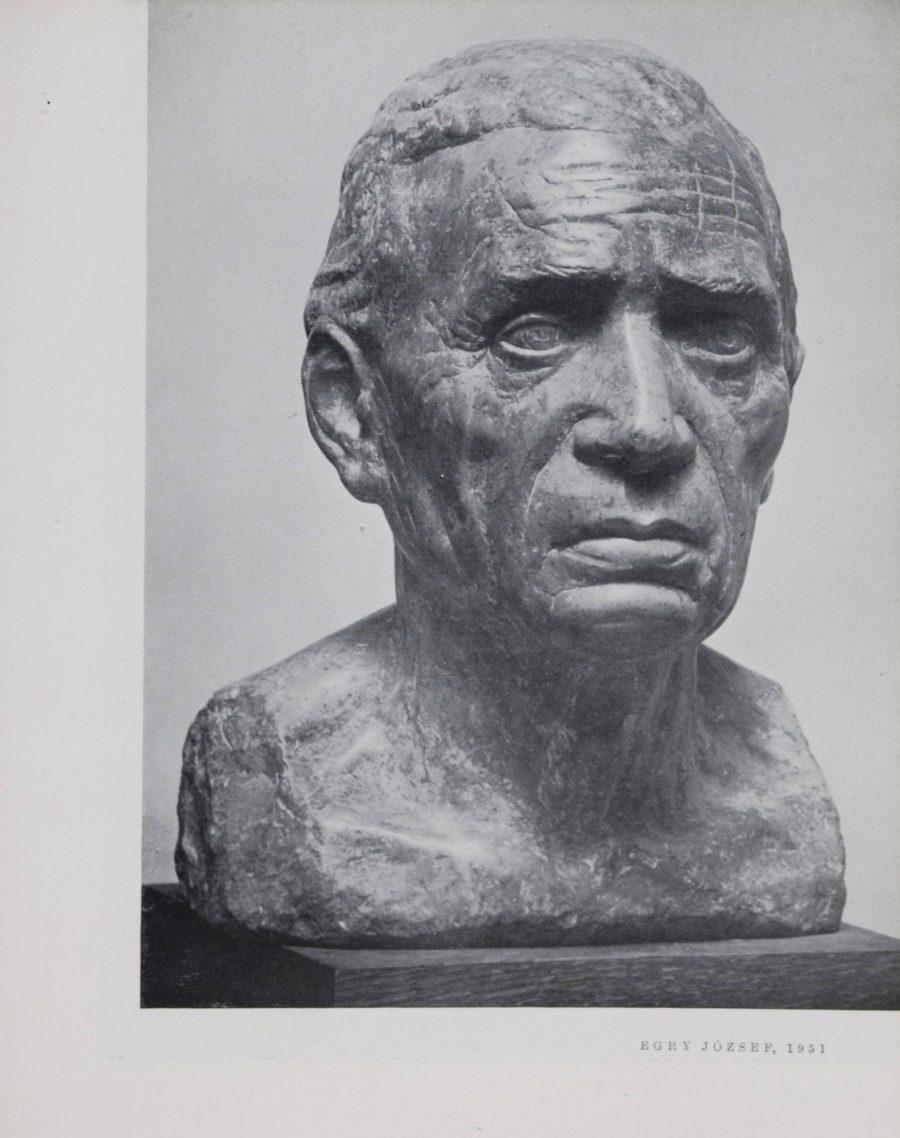

Duchamp’s letter is not the only reason historians have for thinking of Fountain as von Freytag-Loringhoven’s work. “Baroness Elsa had been finding objects in the street and declaring them to be works of art since before Duchamp hit upon the idea of ‘readymades,’” writes Higgs. One such work, a “cast-iron plumber’s trap attached to a wooden box, which she called God” (above), was also misattributed, “assumed to be the work of an artist called Morton Livingston Schaumberg, although it is now accepted that his role in the sculpture was limited to fixing the plumber’s trap to its wooden base.”

“Fountain is base, crude, confrontational and funny,” writes Higgs, “Those are not typical aspects of Duchamp’s work, but they summarize the Baroness and her art perfectly.” Duchamp later claimed to have bought the urinal himself, but later research has shown this to be unlikely. Higgs’ book Stranger Than We Can Imagine explores the issues in more depth, as does an article in Dutch published in the See All This summer issue. What would it mean for the art establishment to acknowledge von Freytag-Loringhoven’s authorship? “To attribute Fountain to a woman and not a man,” the magazine writes, “has obvious, far-reaching consequences: the history of modern art has to be rewritten. Modern art did not start with a patriarch, but with a matriarch.”

Learn more about Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven at The Art Story.

via See All This

Related Content:

Hear Marcel Duchamp Read “The Creative Act,” A Short Lecture on What Makes Great Art, Great

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness