No one art form has done more to shape the world’s sense of traditional Japanese aesthetics than the woodblock print. But not so very long ago, in historical terms, no such works had ever left Japan. That changed when, according to the Library of Congress, “American naval officer Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794–1858) led an expedition to Japan between 1852 and 1854 that was instrumental in opening Japan to the Western world after more than 200 years of national seclusion.” As travelers, materials, and products began flowing between Japan and the West, so did art.

This flow happened, of course, by sea, and so Japanese artists working in woodblock and other forms soon found that the port city of Yokohama had become “an incubator for a new category of images that straddled convention and novelty.”

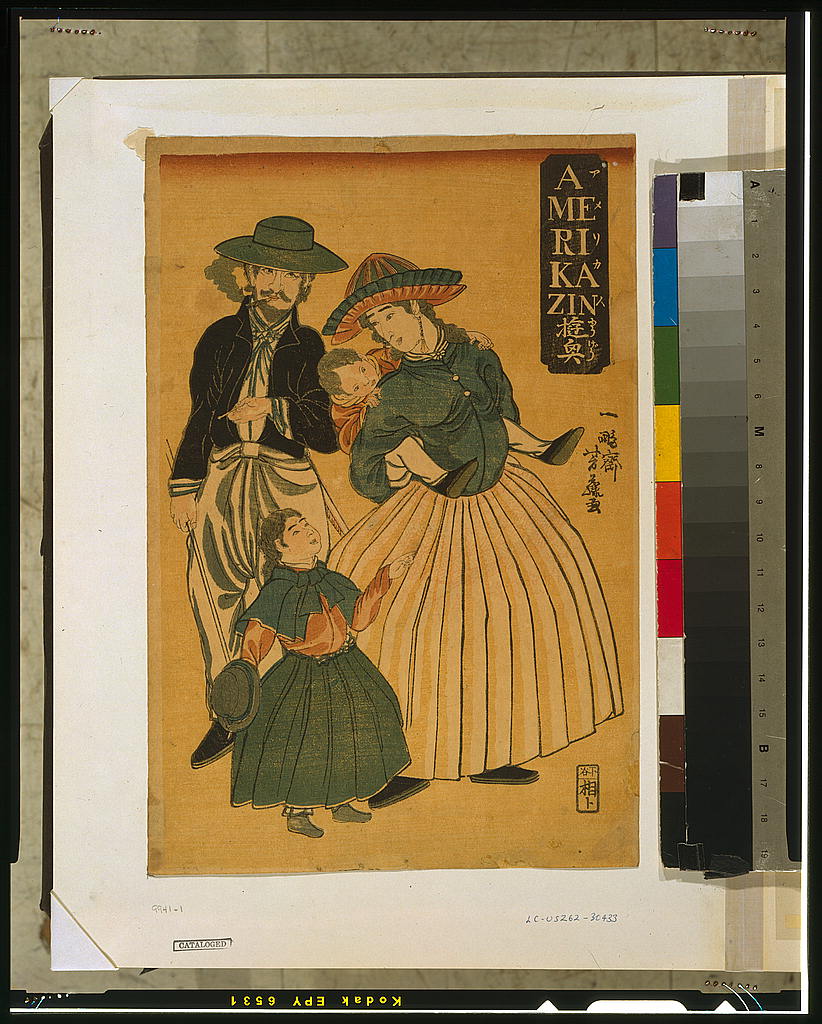

In their depictions of modern Yokohama, “bewhiskered men and crinoline-clad women were shown striding through the city, clambering on and off ships, riding horses, enjoying local entertainments, and interacting with an endless array of objects from goblets to locomotives.” This new genre in an established tradition took on the name “Yokohama‑e,” or “pictures of Yokohama.”

Hundreds of years earlier, during the Tokugawa Period that began in the year 1600, that tradition had already produced the now well-known genre of “Ukiyo‑e,” or “pictures of the floating world,” woodblock depictions of the pleasure districts of Edo, now called Tokyo. “Various forms of entertainment, particularly kabuki theater and the pleasure quarters, lured monied patrons who were eager in turn to acquire the vivid images of celebrated actors and beautiful courtesans.” Later, “travel became a popular form of leisure and the pleasures of the natural environment, interesting landmarks, and the adventures encountered en route also became favorite Ukiyo‑e themes.” Ukiyo‑e also looked to “Japanese myth, legend, literature, history, and daily life” for subjects, and so its prolific artists captured the culture nearly whole.

You can come as close as possible to experiencing that culture by viewing, and downloading, more than 2,500 Japanese woodblock prints and drawings at the Library of Congress’ online collection “Fine Prints: Japanese, pre-1915.” It includes work from such prolific Ukiyo‑e artists as Hokusai Katsushika (whose Teahouse at Koishikawa the Morning After a Snowfall appears at the top of the post), Andō Hiroshige (Minakuchi below that), Isoda Koryūsai (Kisaragi, third from the top), and Utagawa Yoshifuji (whose Amerikajin Yūgyō, one of his depictions of Americans, appears just above). As much as Japan has changed since the heyday of the Yokohama‑e, much less the Ukiyo‑e, any visitor to the country in the 21st century will first notice not how much the surfaces of Japan’s real urban and natural landscapes, domestic interiors, and public scenes differ from those in classical woodblock prints, but how deeply they’ve remained the same.

Enter the collection here.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

The (F)Art of War: Bawdy Japanese Art Scroll Depicts Wrenching Changes in 19th Century Japan

Hayao Miyazaki’s Beloved Characters Reimagined in the Style of 19th-Century Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Philipp Franz von Siebold was a German physician-scientist who worked for the Dutch trading post in Japan, Dejima, from 1823–1830. He collected enormous amounts of plants and other items, including woodblock prints that he transported to the Netherlands, including woodblock prints. There have been suggestions that he even met Hokusai and had the latter paintlandscapes in a European style. However, the major influence of Japanese woodblock prints on European art started much later, around 1869.