Name all the things in space in 20 minutes. Impossible, you say? Well, if there’s anyone who might come close to summarizing the contents of the universe in less than half an hour, with the aid of a handy infographic map also available as a poster, it’s physicist Dominic Walliman, who has explored other vast scientific regions in condensed, yet comprehensive maps on physics, mathematics, chemistry, biology, and computer science.

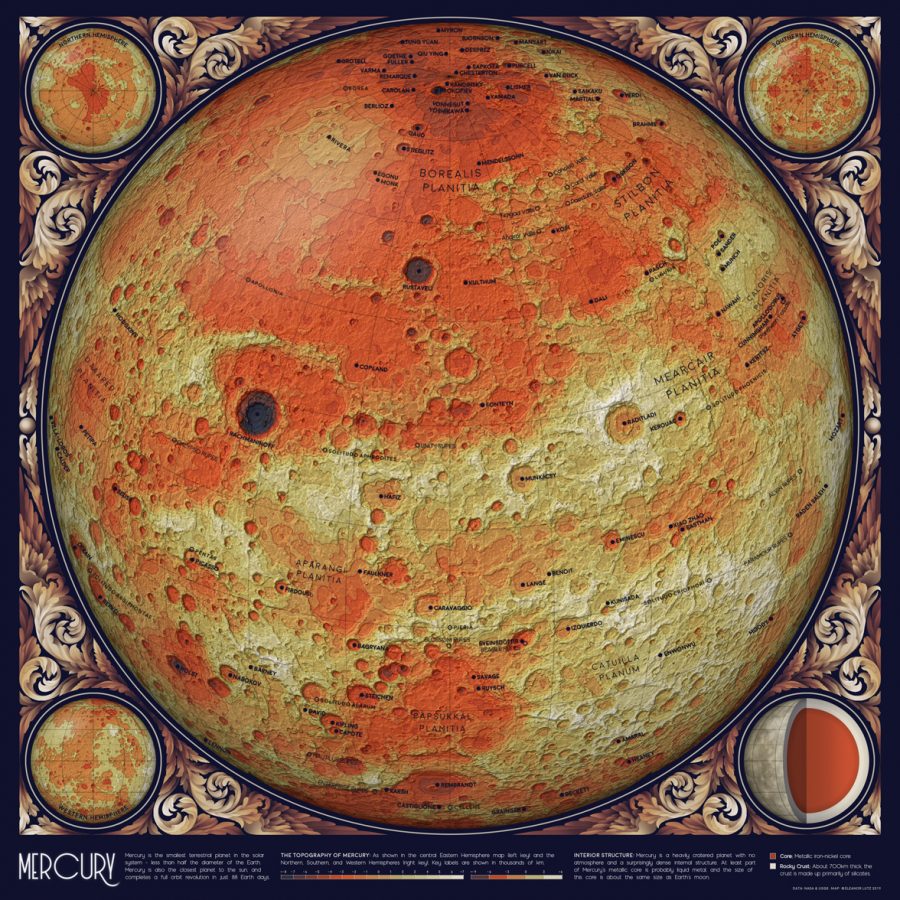

These are all academic disciplines with more or less defined boundaries. But space? It’s potentially endless, a point Walliman grants up front. Space is “infinitely big and there are an infinite number of things in it,” he says. However, these things can still be named and categorized, since “there are not an infinite number of different kinds of things.” We begin at home, so to speak, with the Earth, our Sun, the solar system (and a dog), and the planets: terrestrial, gas, and ice giant.

Asteroids, meteors, comets, dwarf planets, moons, the Kuyper Belt, Dort Cloud, and heliosphere, cosmic dust, black holes…. We’re only two minutes in and that’s a lot of things already—but it’s also a lot of kinds of things, and those kinds repeat over and over. The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way may be a type representing a whole class of things “at the center of every galaxy.”

The universe might contain an infinite number of stars—or a number so large it might as well be infinite. But that doesn’t mean we can’t extrapolate from the comparatively tiny number we’re able to observe as representative of general star behavior: from the “main sequence stars”—Red, Orange, and Yellow Dwarves (like our sun)—to blue giants to variable stars, which pulsate and change in size and brightness.

Massive Red Giants explode into nebulae at the end of their 100 million to 2 billion year lives. They also, along with Red and Orange Dwarf stars, leave behind a core known as a White Dwarf, which will become a Black Dwarf, which does not exist yet because the universe it not old enough to have produced any. “White dwarves,” Walliman says, “will be the fate of 97% of the stars in the universe.” The number of kinds of stars expands, we get into the different shapes galaxies can take, and learn about cosmic radiation and “mysteries.”

This project does not have the scope to include explanations of how we know about these many kinds of space objects, but Walliman does an excellent job of turning what may be the biggest picture imaginable into a thumbnail—or poster-sized (purchase here, download here)—outline of the universe. We cannot ask more from a twenty-minute video promising to name “Every Kind of Thing in Space.”

See other science-defining video maps, all written, researched, animated, edited, and scored by Walliman, at the links below.

Related Content:

The Map of Physics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Physics Fit Together

The Map of Mathematics: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Math Fit Together

The Map of Chemistry: New Animation Summarizes the Entire Field of Chemistry in 12 Minutes

The Map of Biology: Animation Shows How All the Different Fields in Biology Fit Together

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness