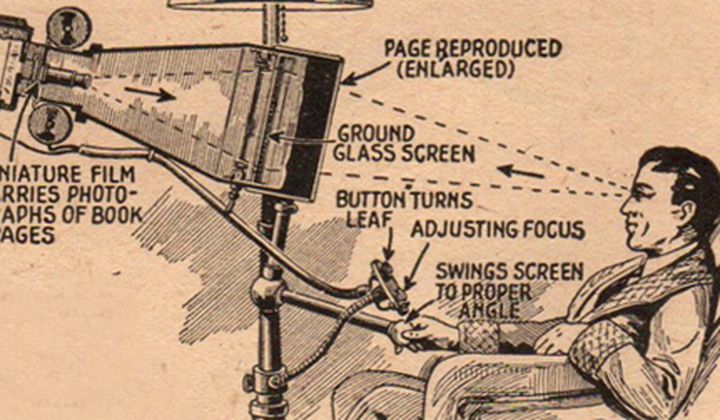

What is the future of the book? Will it retain more or less the same basic paper-between-covers form as it has since the days of the Gutenberg Bible? Will it go entirely digital, becoming readable only with compatible electronic devices? Or will we, in the comfort of our armchairs, read them on glass-screened microfilm projectors? That last is the bet made, and illustrated as above, by the April 1935 issue of Everyday Science and Mechanics magazine. “It has proved possible to photograph books, and throw them on a screen for examination,” says the article envisioning “a device for applying this for home use and instruction,” exhumed by Matt Novak at Smithsonian.com.

As The Atlantic’s Megan Garber writes, “The whole thing, to our TV-and-tablet-jaded eyes, looks wonderfully quaint. (The projector! The knobs! The semi-redundant reading lamp! The smoking jacket!)” But then, “what speaks to our current, hazy dreams of convergence more eloquently than the ability to sit back, relax, and turn books into television?”

And indeed, the original illustration includes a caption telling us how such a device will allow you to “read a ‘book’ (which is a roll of miniature film), music, etc., at your ease.” That may sound familiar to those of us who think nothing of flipping back and forth between books, web sites, movies, television shows, and social media — all to our customized music-and-podcast soundtrack of choice — on our computers, tablets, and phones today.

Everyday Science and Mechanics wasn’t looking into the distant future. As Novak notes, microfilm had been patented in 1895 and first practically used in 1925; the New York Times began copying its every edition onto microfilm in 1935, the same year this article appeared. As impractical as it may look now, this home “e‑reader” could theoretically have been put into use not long thereafter. As it happened, the first e‑readers — the handheld digital ones of the kind we know today — wouldn’t come on the market for another 70 years, and their widespread adoption has only occurred in the past decade. But for many, good old Gutenberg-style paper-between-covers remains the way to read. It may be that the book has no one future form, but a variety that will exist at once — a variety that, absent a much stronger retrofuturism revival, will probably not include microfilm, ground-glass screens, and smoking jackets.

via Smithsonian.com

Related Content:

Readers Predict in 1936 Which Novelists Would Still Be Widely Read in the Year 2000

1930s Fashion Designers Predict How People Would Dress in the Year 2000

Did Stanley Kubrick Invent the iPad in 2001: A Space Odyssey?

Napoleon’s Kindle: See the Miniaturized Traveling Library He Took on Military Campaigns

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.