The New York Public Library sure knows how to celebrate a quasquicentennial. In honor of its own 125th anniversary, it’s rolling out a number of treats for patrons, visitors, and those who must admire it from afar.

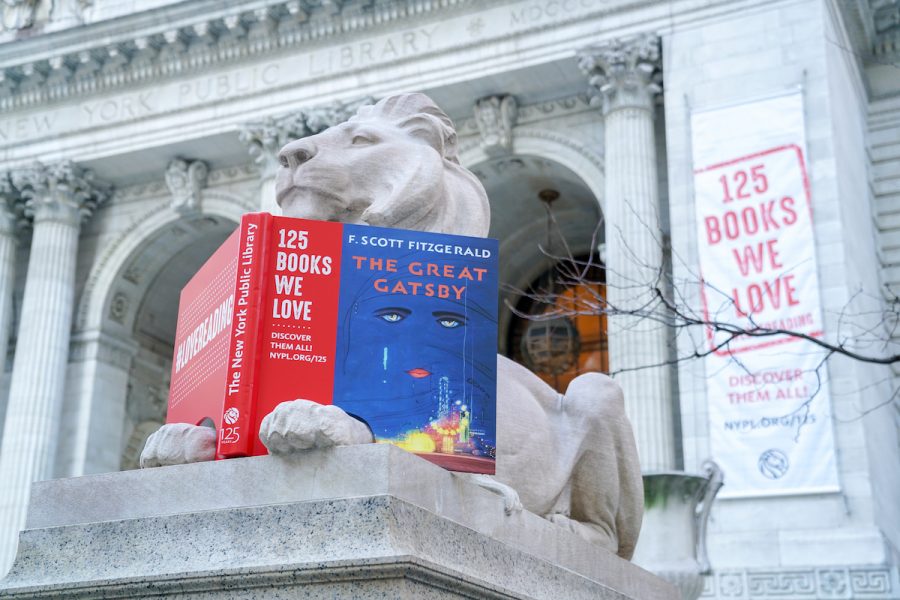

In addition to the expected author talks and live events, Patience and Fortitude, the iconic stone lions who flank the main branch’s front steps, are displaying some reading material of their own—Toni Morrison’s 1987 novel Beloved and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age classic The Great Gatsby, from 1925.

Donors who kick in $12.50 or more to help the library continue providing such public services as early literacy classes, free legal aid, and job training courses will be rewarded with a cheerful red sticker bearing the easy to love slogan “♥ reading.”

The cover image of Ezra Jack Keats’ 1962 Caldecott Award-winning picture book The Snowy Day, which at 485,583 checkouts holds the title for most popular book in the circulating collection, graces special edition Library and MetroCards.

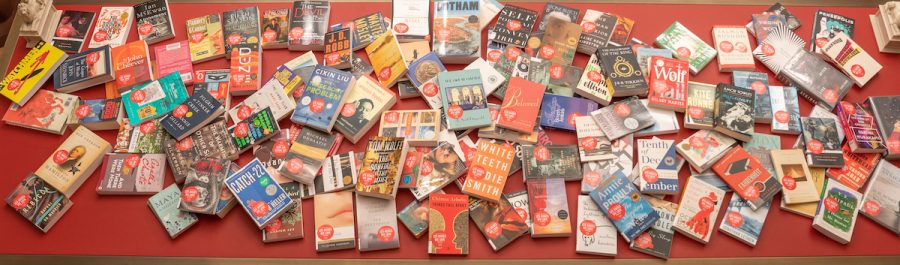

And a team of librarians drew up a list of 125 books from the last 125 years that inspire a lifelong love of reading.

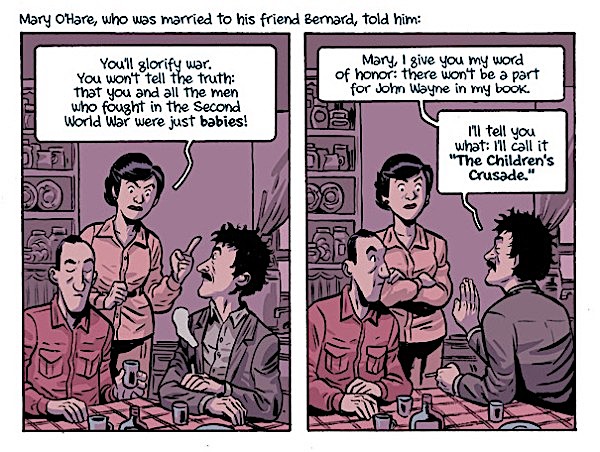

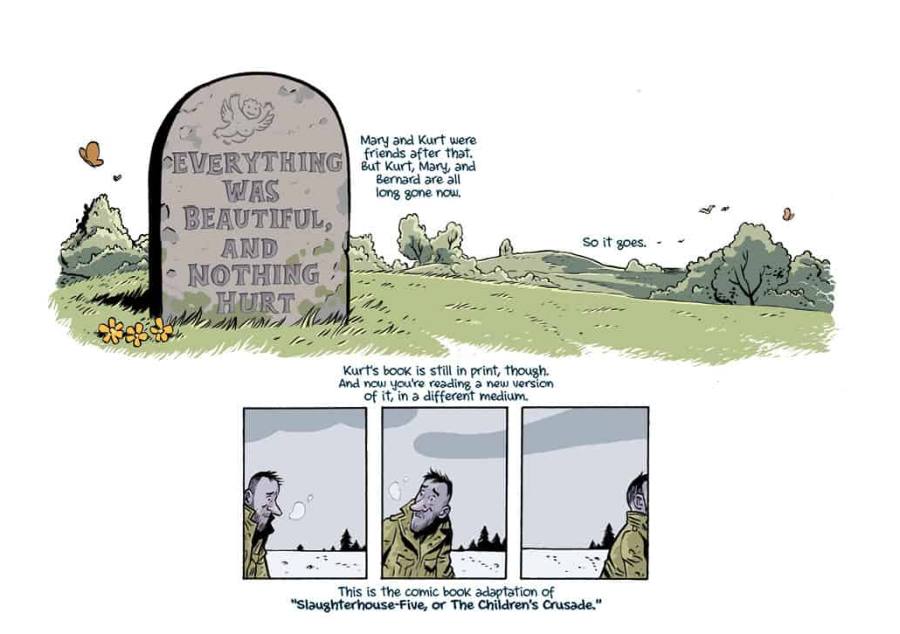

The list is deliberately inclusive with regard to authors’ gender, race, and sexual orientation as well as literary genre. In addition to novels and non-fiction, you’ll find memoir, poetry, fantasy, graphic novels, science fiction, mystery, short stories, humor, and one children’s book, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, which the judges decided “transcends age categories.” (A similar list geared toward younger readers will be released later this year.)

The list was drawn from a pool containing anything published after May 23rd, 1895, the day attorney John Bigelow’s plan to combine the resources of the Astor and Lenox libraries and the Tilden Trustin into The New York Public Library was officially incorporated.

The selection criteria can be viewed here.

Obviously, the list—and any perceived omissions—will generate passionate debate amongst book lovers, a prospect the library relishes, though it’s enlisted one of its most ardent supporters, author Neil Gaiman, whose American Gods made the final cut, to remind any disgruntled readers of the spirit in which the picks were made:

The New York Public Library has put together a list of 125 books that they love—the librarians and the people in the library. That’s the criteria. You may not love them, but they do. And that’s exciting. The thing that gets people reading is love. The thing that makes people pick up books they might not otherwise try, is love. It’s personal recommendations, the kind that are truly meant. So here are 125 books that they love. And somewhere on this list you will find books you’ve never read, but have always meant to, or have never even heard of. There are 125 chances here to change your own life, or to change someone else’s, curated by the people from one of the finest libraries in the world. Read with joy. Read with love. Read!

To really get the most out of the list, tune in to the NYPL’s The Librarian Is In podcast, which will be devoting an episode to one of the featured titles each month.

The current episode kicks things off with co-hosts Frank Collerius and Rhonda Evans’ favorites from the list:

Maus by Art Spiegelman

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Readers, have a look at the complete list of the New York Public Library’s 125 Books for Adult Readers, and leave us a comment to let us know what titles you wish had been included. Or better yet, tell us which as-yet unread title you’re planning to read in honor of the New York Public Library’s 125th year:

George Orwell, 1984

Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March

W.H. Auden, The Age of Anxiety

Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton

Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front

James Patterson, Along Came a Spider

Michael Chabon, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

Neil Gaiman, American Gods

Mary Oliver, American Primitive

Agatha Christie, And Then There Were None

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts

Sylvia Plath, Ariel

Ian McEwan, Atonement

Anne Carson, Autobiography of Red

Toni Morrison, Beloved

Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep

Tom Wolfe, The Bonfire of the Vanities

Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited

Colm Tóibín, Brooklyn

Joseph Heller, Catch-22

J.D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

Claudia Rankine, Citizen

Stacy Schiff, Cleopatra

David Mitchell, Cloud Atlas

Langston Hughes, The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes

Terry Pratchett, The Color of Magic

Alice Walker, The Color Purple

Walter Mosley, Devil in a Blue Dress

Erik Larson, The Devil in the White City

Frank Herbert, Dune

Michael Ondaatje, The English Patient

Alyssa Cole, An Extraordinary Union

Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

J.R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

N.K. Jemisin, The Fifth Season

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home

George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

Arundhati Roy, The God of Small Things

Flannery O’Connor, A Good Man is Hard to Find

Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House

Carson McCullers, The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter

Dave Eggers, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Arthur Conan Doyle, The Hound of the Baskervilles

V.S. Naipaul, A House for Mr. Biswas

Edith Wharton, The House of Mirth

Marilynne Robinson, Housekeeping

Allen Ginsberg, Howl

Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

Truman Capote, In Cold Blood

Beverly Jenkins, Indigo

Jhumpa Lahiri, Interpreter of Maladies

Jon Krakauer, Into Thin Air

Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

Gore Vidal, Julian

Khaled Hosseini, The Kite Runner

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness

Mary Karr, The Liars’ Club

Kate Atkinson, Life After Life

Tracy K. Smith, Life on Mars

Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

Art Spiegelman, Maus

David Sedaris, Me Talk Pretty One Day

John Berendt, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil

Salman Rushdie, Midnight’s Children

Martin Amis: Money

Michael Lewis: Moneyball

Jonathan Lethem, Motherless Brooklyn

Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Elena Ferrante, My Brilliant Friend

J.D. Robb, Naked in Death

Richard Wright, Native Son

Elizabeth Strout, Olive Kitteridge

Jack Kerouac, On the Road

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Jeanette Winterson, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit

Adam Johnson, The Orphan Master’s Son

Per Petterson, Out Stealing Horses

Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower

Marjane Satrapi, Persepolis

Annie Dillard, Pilgrim at Tinker Creek

Philip Roth, Portnoy’s Complaint

Graham Greene, The Quiet American

Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day

Louise Erdrich, The Round House

Amor Towles, Rules of Civility

Alice Munro, Runaway

John Ashbery, Self-Portrarit in a Convex Mirror

Stephen King, The Shining

Annie Proulx, The Shipping News

Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Nalini Singh, Slave to Sensation

Joan Didion, Slouching Towards Bethlehem

Leslie Feinberg, Stone Butch Blues

John Cheever, The Stories of John Cheever

Albert Camus, The Stranger

Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises

Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley

George Saunders, Tenth of December

Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart

Cixin Liu, The Three-Body Problem

Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

Denis Johnson, Train Dreams

Henry James, The Turn of the Screw

Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

Joseph Mitchell, Up in the Old Hotel

Jeffrey Eugenides, The Virgin Suicides

Jennifer Egan, A Visit from the Goon Squad

Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, Watchmen

Raymond Carver, What We Talk About When We Talk About Love

Don DeLillo, White Noise

Zadie Smith, White Teeth

Haruki Murakami, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Hilary Mantel, Wolf Hall

Maxine Hong Kingston, The Woman Warrior

Via Lit Hub

Related Content:

The New York Public Library Announces the Top 10 Checked-Out Books of All Time

New York Public Library Card Now Gives You Free Access to 33 NYC Museums

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join Ayun’s company Theater of the Apes in New York City this March for her book-based variety series, Necromancers of the Public Domain, and the world premiere of Greg Kotis’ new musical, I AM NOBODY. Follow her @AyunHalliday.