The coronavirus has closed libraries in countries all around the world. Or rather, it’s closed physical libraries: each week of struggle against the epidemic that goes by, more resources for books open to the public on the internet. Most recently, we have the Internet Archive’s opening of the National Emergency Library, “a collection of books that supports emergency remote teaching, research activities, independent scholarship, and intellectual stimulation while universities, schools, training centers, and libraries are closed.” While the “national” in the name refers to the United States, where the Internet Archive operates, anyone in the world can read its nearly 1.5 million books, immediately and without waitlists, from now “through June 30, 2020, or the end of the US national emergency, whichever is later.”

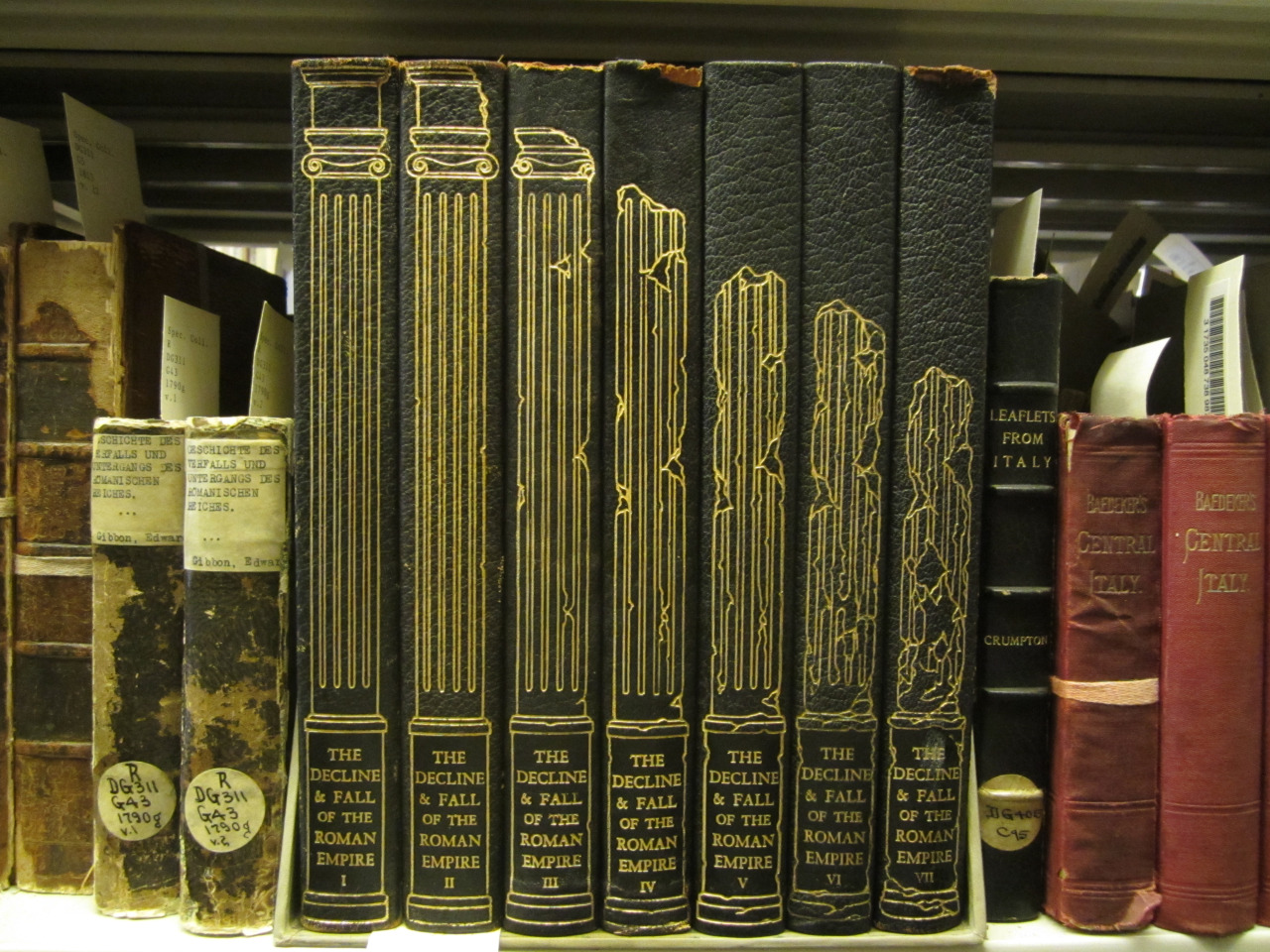

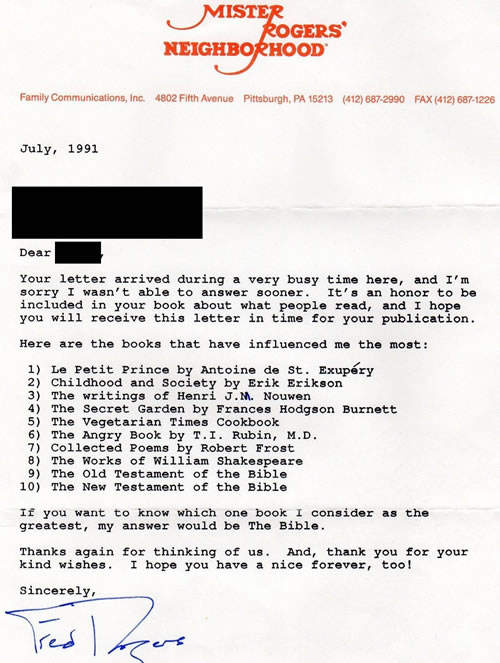

“Not to be sneezed at is the sheer pleasure of browsing through the titles,” writes The New Yorker’s Jill Lepore of the National Emergency Library, going on to mention such volumes as How to Succeed in Singing, Interesting Facts about How Spiders Live, and An Introduction to Kant’s Philosophy, as well as “Beckett on Proust, or Bloom on Proust, or just On Proust.” A historian of America, Lepore finds herself reminded of the Council on Books in Wartime, “a collection of libraries, booksellers, and publishers, founded in 1942.” On the premise that “books are useful, necessary, and indispensable,” the council “picked over a thousand volumes, from Virginia Woolf’s The Years to Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, and sold the books, around six cents a copy, to the U.S. military.” By practically giving away 120 million copies of such books, the project “created a nation of readers.”

In fact, the Council on Books in Wartime created more than a nation of readers: the American “soldiers and sailors and Army nurses and anyone else in uniform” who received these books passed them along, or even left them behind in the far-flung places they’d been stationed. Haruki Murakami once told the Paris Review of his youth in Kobe, “a port city where many foreigners and sailors used to come and sell their paperbacks to the secondhand bookshops. I was poor, but I could buy paperbacks cheaply. I learned to read English from those books and that was so exciting.” Seeing as Murakami himself later translated The Big Sleep into his native Japanese, it’s certainly not impossible that an Armed Services Edition counted among his purchases back then.

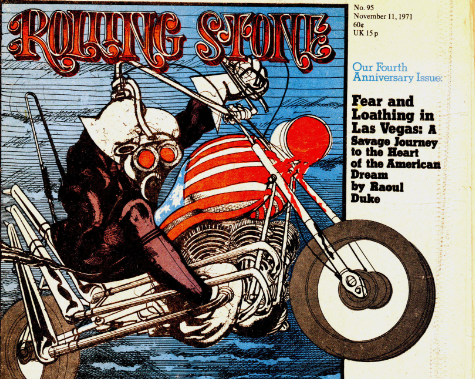

Now, in translations into English and other languages as well, we can all read Murakami’s work — novels like Norwegian Wood and Kafka on the Shore, short-story collections like The Elephant Vanishes, and even the memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running — free at the National Emergency Library. The most popular books now available include everything from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale to the Kama Sutra, Dr. Seuss’s ABC to Alvin Schwartz’s Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark (and its two sequels), Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart to, in disconcerting first place, Sylvia Browne’s End of Days: Predictions and Prophecy About the End of the World. You’ll even find, in the original French as well as English translation, Albert Camus’ existential epidemic novel La Peste, or The Plague, featured earlier this month here on Open Culture. And if you’d rather not confront its subject matter at this particular moment, you’ll find more than enough to take your mind elsewhere. Enter the National Emergency Library here.

Related Content:

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

11,000 Digitized Books From 1923 Are Now Available Online at the Internet Archive

Free: You Can Now Read Classic Books by MIT Press on Archive.org

Enter “The Magazine Rack,” the Internet Archive’s Collection of 34,000 Digitized Magazines

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.