?si=ILR3sREkYPwPDwsP

Last week we featured the first three films of Stanley Kubrick. Today we focus on the first three by Martin Scorsese. Although the two men were about the same age when they ventured into filmmaking, and faced similar constraints, their earliest films are strikingly different.

Kubrick and Scorsese had both grown up in New York City and gone to high school in the Bronx, but their circumstances were worlds apart. Kubrick failed to get into college after high school because of bad grades but, as he put it, “backed into a fantastically good job at the age of seventeen” working as a staff photographer for Look magazine. Scorsese went to college and studied the history and aesthetics of cinema. When Kubrick decided to try his hand at motion pictures he was driven by a sense of economic urgency. His strategy was to get a foothold in the marketplace by beating the newsreel industry at its own game. Scorsese, on the other hand, was sheltered from economic worries. He was moved instead by the vivacity and inventiveness of French New Wave cinema, among other influences, and wanted to assert himself as the next great auteur.

As a severely asthmatic child, Scorsese went to the movies often. When high school graduation was approaching he thought about becoming a priest, and briefly considered studying literature. But then something caught his eye: a catalog for the New York University film school. He went to an NYU orientation session, where the various department heads took turns describing their programs to a room filled with prospective students. When the head of the Department of Television, Motion Pictures and Radio stood up–a man named Haig Manoogian–the young Scorsese was instantly impressed. “He had such energy, such passion,” Scorsese tells Richard Schickel in Conversations with Scorsese. “I said to myself, That’s where I want to be, with this person.”

Manoogian took the art of film very seriously. When Scorsese was a freshman in 1960 he attended Manoogian’s once-a-week class on the history of film. Each session included a lecture and the screening of a film. In Conversations with Scorsese the filmmaker remembers Manoogian’s ruthlessness in dealing with students who attended only to watch movies. “He’d say, okay, you don’t come back, you don’t come back,” says Scorsese, “ ‘because some of you must think because we’re showing movies, it’s fun. Get out.’ ”

As Scorsese moved through the program, he gradually began learning a few basic skills in the mechanics of making a movie. By junior year, each student was expected to collaborate in the making of a short film. So in 1963 Scorsese took Manoogian’s summer workshop, where he found that not every student got to direct. “He’d say, Okay, you’re director, you’re grip, you’re camera, whatever,” Scorsese tells Schickel. “So there were a lot of people who were very unhappy.” He quickly figured out that Manoogian was assigning the role of director to students who had their own screenplay. “What I did was write a script and get it to him as soon as possible, and he okayed it, so I was given a crew, and they all knew that they had to do what I wanted.”

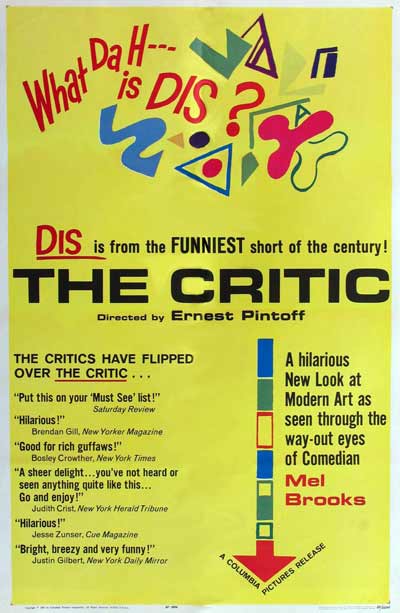

Scorsese and his crew took one of the school’s old 16mm Bell & Howell Filmo cameras and shot a one-reel comedy in a week. He would later describe the film as “nine minutes of visual nonsense.” What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This?, as it is called, (see above) adopts the surreal comic sensibility Scorsese admired in the work of Mel Brooks and Ernie Kovaks, along with narrative technique he picked up watching French New Wave films, particularly those of François Truffaut. As he tells Schickel:

My little film had all the tricks and fun of just putting pictures together in slow motion and fast motion and stills, and intercutting with mattes the way Truffaut would do in Jules and Jim. It had no depth at all, but it was a lot of fun. And it won me a scholarship, so my father was able to use it for the tuition for the next year. And then that led me to doing another short film in my junior year, the second semester, and that became It’s Not Just You, Murray!

It’s Not Just You, Murray! part one:

It’s Not Just You, Murray! part two:

It’s Not Just You, Murray! (above), completed in 1964, is a much more ambitious film. It tells the story of a pair of Italian-American gansters. “The two characters, Murray and Joe,” Scorsese tells Michael Henry Wilson in Scorsese on Scorsese, “are close friends, but the sort who are constantly stealing from each other, pinching their whisky and their girls. They live the way I myself was living with my buddies–relationships that contain as much hate as love.”

Scorsese chose not to present Murray as a gangster at the beginning of the film, because he wanted to make a wider statement about American life. “I grew up in Little Italy,” he tells Wilson, “I’ve seen corruption up close, I’ve seen it operating every day. After that you can’t take the Establishment seriously. It’s all a fraud.” The two-reel film is like a preliminary sketch for some of Scorsese’s most famous later films. When Schickel tells Scorsese he had never seen It’s Not Just You, Murray!, he is surprised by the filmmaker’s description. “It was basically Goodfellas,” Scorsese says. “Huh,” says Schickel?

It’s Goodfellas. I did it in 1964. Murray was a big epic, as much as I could manage, of two guys who were friends in the underworld, from my old neighborhood. but I did it with very New Wave techniques. It was also a cross with The Roaring Twenties, an attempt at that sort of scale which led eventually to Mean Streets, which led ultimately to Goodfellas, and to Casino and Gangs of New York–the scale of it, the excessive nature of it. I mean, in Murray there’s just a hint of it. We didn’t have the money.

The Big Shave:

After Scorsese received his bachelor’s degree from NYU in 1964, he began work on his first feature film, Who’s That Knocking at My Door? It took him over two years to make, and in 1967 he still hadn’t found a distributor. At that time he received a grant from the Cinémathèque de Belgique to make a short film. The result was the third film by Scorsese to be released, and his first in color: The Big Shave (above). “In a bathroom that may represent the American Psyche haunted by the Vietnam war,” writes Wilson in a synopsis of the film, “the daily ritual of shaving turns into a scene of horror.”

As Scorsese tells Mary Pat Kelly in Martin Scorsese: The First Decade, “It grew out of my feelings about Vietnam. But in reality something else was going on inside of me, I think, which really had nothing to do with the war.” Scorsese was experiencing a number of professional and personal setbacks, and was deeply depressed at the time. “After separating from my wife,” he tells Wilson, “I was camping out in empty, creepy apartments.” He continues:

When I wrote the script, I was very serious, but while we were shooting it we never stopped laughing. Watching the rushes, we were doubled up. It was only afterwards that I tried to rationalize what I had done. I almost convinced myself that it was a film against the Vietnam war, that this guy who shaves so meticulously and ends up cutting his throat represented the average American of his day. It was because of these political implications that I used Bunny Berigan’s original 1939 version of “I Can’t Get Started” for the soundtrack. I even wanted to end with archival images of Vietnam, but I didn’t need them. The Big Shave was really a fantasy, a strictly personal vision of death.

You can find the Scorsese films mentioned above in our collection of Free Movies Online.