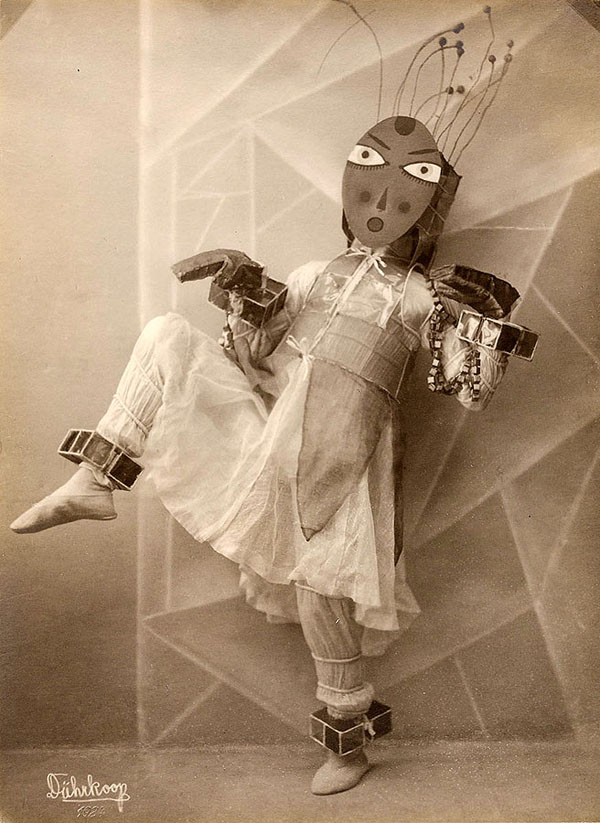

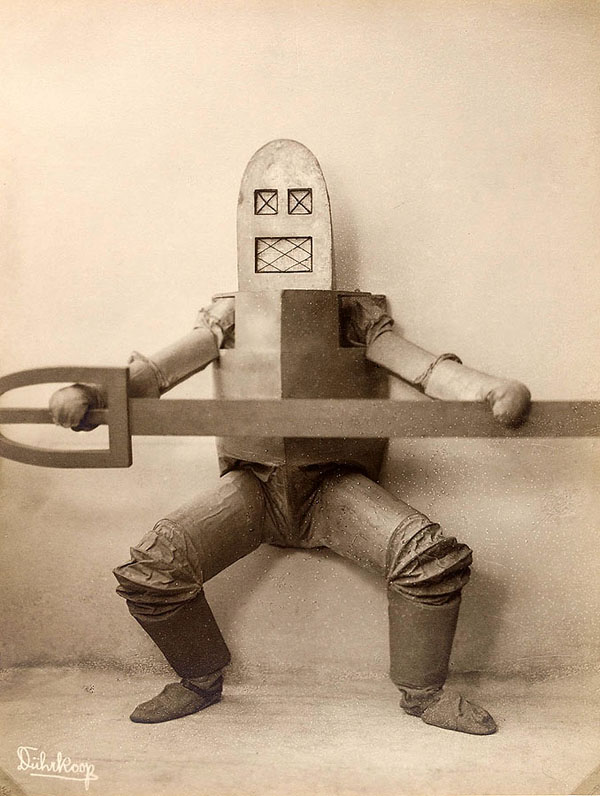

The most fruitful creative partnerships, long or short, have often been tempestuous. On the shorter side, and among the stormiest, we have a husband-and-wife team who realized visions hitherto unseen onstage, and who very nearly fell into total obscurity after a murder-suicide brought their partnership to an end. But in the Hamburg of the late 1910s and early 1920s, writes Hyperallergic’s Allison Meier, Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt “created wild, Expressionist costumes that looked like retro robots and Bauhaus knights,” twenty of them, for performances accompanied by avant-garde music. After their death in 1924, Schulz and Holdt’s work went into storage, never to be found again until the late 1980s.

The costumes had been gifted to the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, which in 1925 “staged an evening in memory of Lavinia Schulz and Walter Holdt,” writes blogger Jan Reetze.

“After this, the masks, photos and drawings” — including dances diagrammed in a system of Schulz’s own invention — “went into a couple of ‘acrobat’s baggage’ boxes and fell into oblivion on the museum’s attic. They were not even inventoried. Which turned out to be a stroke of luck because this way the objects didn’t fall into the hands of the Nazis, who, without any doubt, would have seen these works as ‘degenerate art’ and in all probability would have destroyed them.”

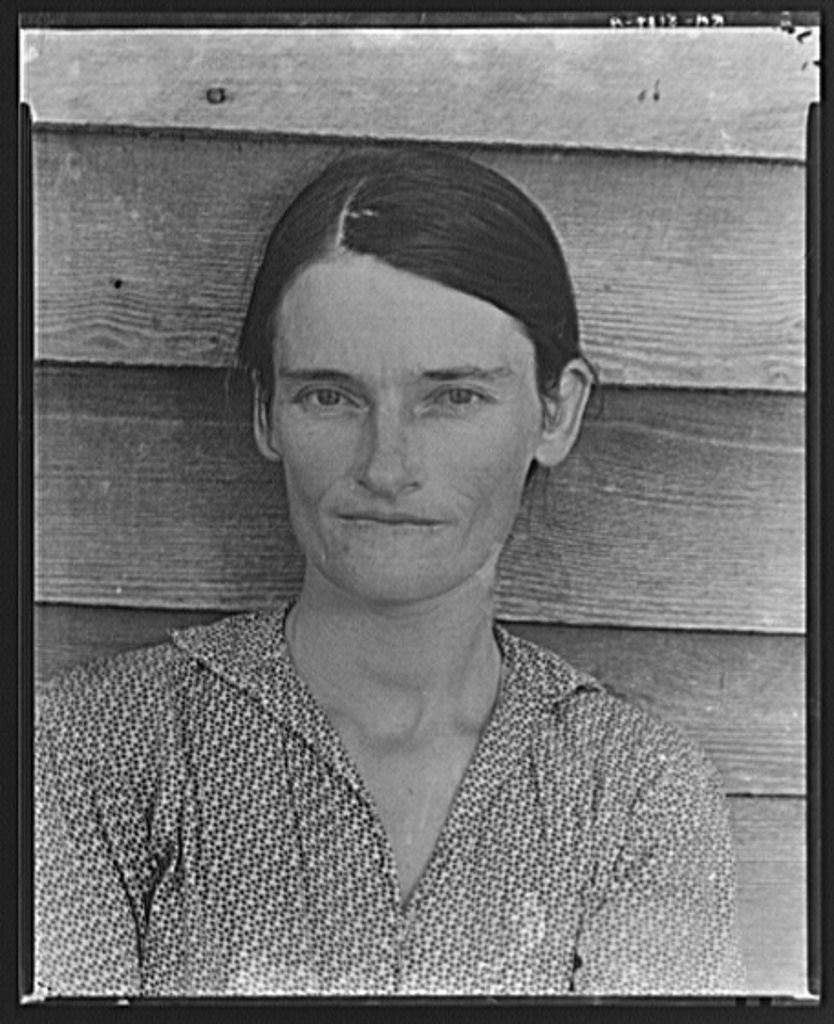

You can see the costumes in action in the video at the top of the post, and more of the photos taken by Minya Diez-Dührkoop in the last year of Schulz and Holdt’s lives at Hyperallergic. Their performances began in the expressionism with which the Berlin-educated Schultz had been associated and moved toward “the supposed purity of pre-Judeo-Christian, Aryan-Nordic culture,” as Dangerous Minds’ Paul Gallagher writes.

“Between 1920–24, the couple performed their dance routines to the bewildered and often antagonistic audiences of Hamburg. Though some critics appreciated the pair’s talent and startling originality, this praise was never enough to pay the rent.”

“According to contemporary critics, Lavinia seemed to be the more creative one,” writes Reetze. “Walter, on the other hand, was the better and more disciplined dancer, he exactly knew his formal means and how to use them.” The counterpart to Holdt’s rigor was Schulz’s more primal genius, a sensibility that manifested aesthetically — seen in her highly unconventional use of everyday materials like “wire, gypsum, papier mâché and industrial garbage” — and emotionally.

Reetze quotes from the autobiography of composer Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, who briefly lived with the couple: “Deprivation, hunger, coldness, nordic landscape with storm, ice, and catastrophes: That was her world, and she had found herself in it with Holdt.”

Schulz and Holdt also refused to be paid for their performances. “You cannot sell spiritual ideas for money,” Schulz wrote. “Spirit and money are two antagonistic poles, and if you sell spiritual ideas for money, you sold the spirit to the money and lost the spirit.” Eventually their poverty — as well as the unusually volatile nature of their relationship, said to spark physical marital spats on stage — reached a breaking point. “Both were in their 20s, and had earned little money from their artistic work,” writes Meier. “In financial ruin, on June 18, 1924, Schulz shot Holdt, and then turned the gun on herself.” But against all odds, their still-startling creativity — the kind that can, perhaps, emerge only from the opposition of two incompatible forces — lives on.

via Dangerous Mind

Related Content:

1930s Fashion Designers Predict How People Would Dress in the Year 2000

An Online Trove of Historic Sewing Patterns & Costumes

Harvard Puts Online a Huge Collection of Bauhaus Art Objects

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.