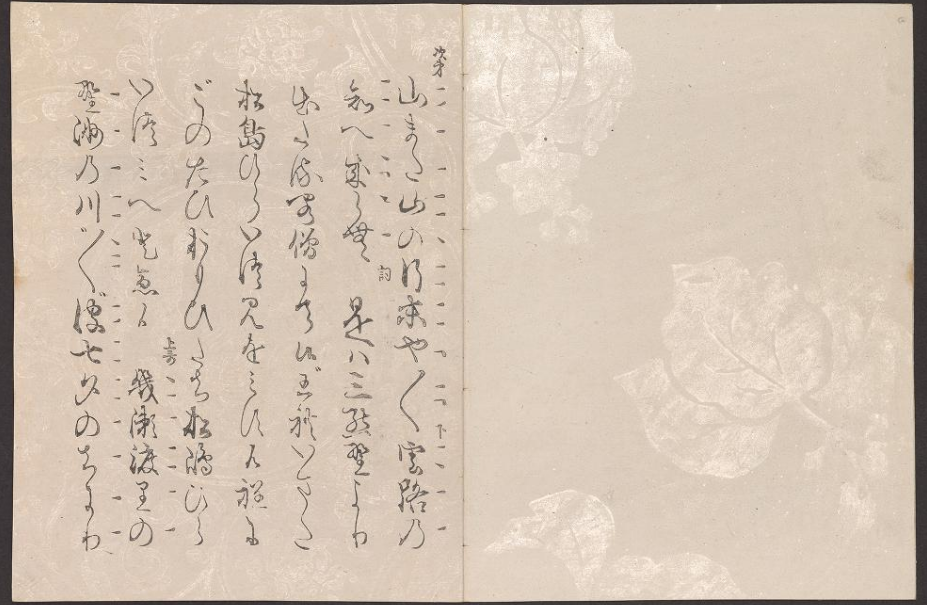

It has 240 pages filled with writing and illustration. Carbon dating places it around the year 1420. Scholars have spent countless thousands of hours scrutinizing it. But the so-called Voynich Manuscript has one quality more notable than any other: nobody understands a word of it. Last month, Josh Jones wrote about this singularly strange textual artifact here at Open Culture, including the digitized version at the Internet Archive that you can flip through and read yourself — or rather “read,” since the text’s language, if it be a language at all, remains unidentified. But before you do that, you might want to watch TED-Ed’s brief introduction to the Voynich Manuscript above.

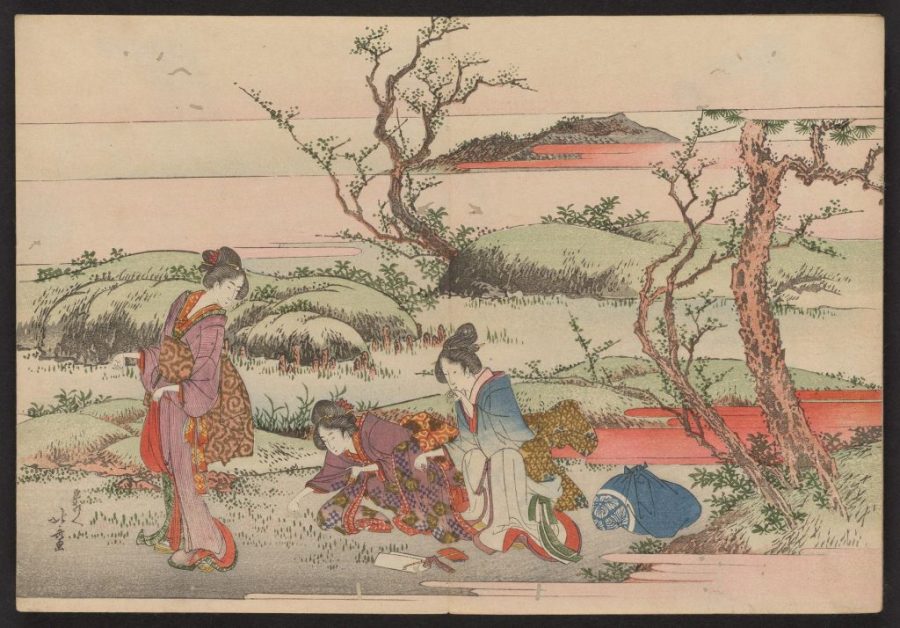

The video’s narrator describes pages of “real and imaginary plants, floating castles, bathing women, astrology diagrams, zodiac rings, and suns and moons with faces accompany the text,” reading from a script by Stephen Bax, Voynich Manuscript researcher and Professor of Modern Languages and Linguistics at the Open University.

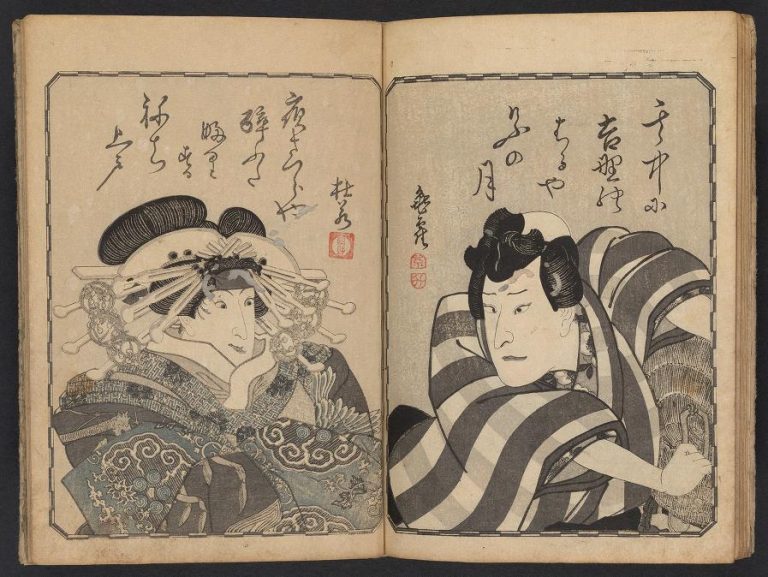

“Cryptologists say the writing has all the characteristics of a real language — just one that no one’s ever seen before.” Highly decorated throughout with “scroll-like embellishments,” the manuscript features the work of what looks like no fewer than three hands: two who did the writing, and one who did the painting.

Intrigued yet? Or perhaps you already feel an inkling of a new theory to explain this bizarre, seemingly encyclopedia-like volume’s provenance to add to the many that have come before: some believe the manuscript’s author or authors wrote it in code, some that “the document is a hoax, written in gibberish to make money off a gullible buyer” by a “medieval con man” or even Voynich himself, and some that it shows an attempt “to create an alphabet for a language that was spoken, but not yet written.” Maybe the thirteenth-century philosopher Roger Bacon wrote it. Or maybe the Elizabethan mystic John Dee. Or maybe Italian witches, or space aliens. At just a glance, the Voynich Manuscript poses questions that could take an eternity to answer — as any great work of literature should.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.