Where were you on November 22, 1963?

I had yet to be born, but am given to understand that the events of that day helped shape a generation.

Documentarian Melanie Juliano knows this too, though she’s still a few months shy of the legal drinking age. The 2014 recipient of the New Jersey Filmmakers of Tomorrow Festival’s James Gandolfini Best of Fest Award uses primary sources and archival footage to bring an immediacy to this dark day in American history, the day a giant octopus—“a giant fuckin’ octopus” in the words of maritime expert Joey Fazzino—took down the Cornelius G. Kolff and all 400 hundred souls aboard.

What did you think I was talking about, the Kennedy assassination?

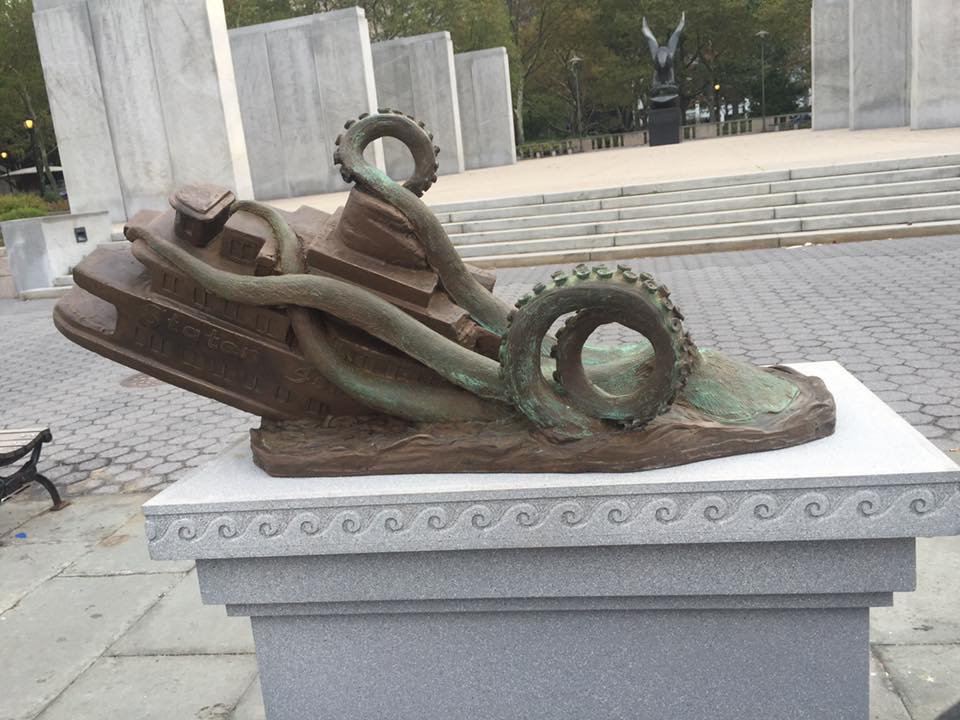

Image via the Facebook page of the Staten Island Ferry Octopus Disaster Memorial Museum

Those who would question this tragedy’s authenticity need look no further than a recently dedicated bronze memorial in Lower Manhattan’s Battery Park. To require more proof than that is unseemly, nay, cruel. If an estimated 90% of tourists stumbling across the site are willing to believe that a giant octopus laid waste to a Manhattan-bound Staten Island ferry several hours before John F. Kennedy was shot, who are you to question?

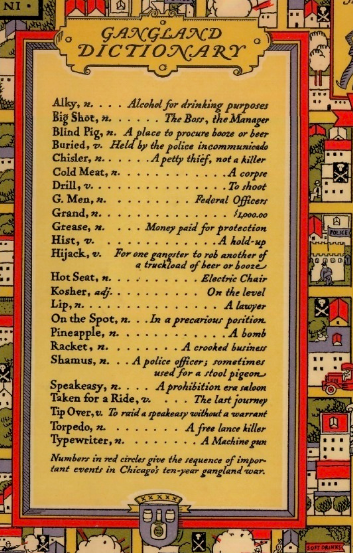

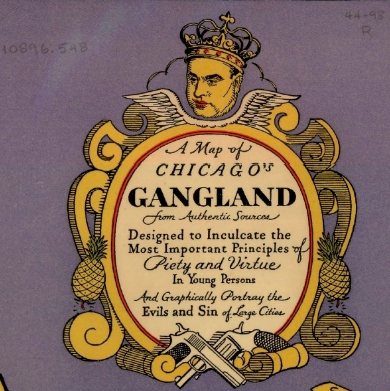

The memorial’s artist, Joe Reginella, of the Staten Island-based Super Fun Company, is finding it hard to disengage from a disaster of this magnitude. Instead the craftsman, whose previous work includes a JAWS tribute infant crib, lingers nearby, noting visitors’ reactions and handing out literature for the (non-existent) Staten Island Ferry Disaster Memorial Museum.

(New York 1 reports that an actual museum across the street from the address listed on Reginella’s brochures is not amused, though attendance is up.)

A Staten Island Octopus Disaster website is there for the edification of those unable to visit in person. Spend time contemplating this horrific event and you may come away inspired to learn more about the General Slocum disaster of 1904, a real life New York City ferry boat tragedy, that time has virtually erased from the public consciousness.

(The memorial for that one is located in an out of the way section of Tompkins Square Park.)

H/T to reader Scott Hermes/via Colossal

Related Content:

The Dancer on the Staten Island Ferry

“Moon Hoax Not”: Short Film Explains Why It Was Impossible to Fake the Moon Landing

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.