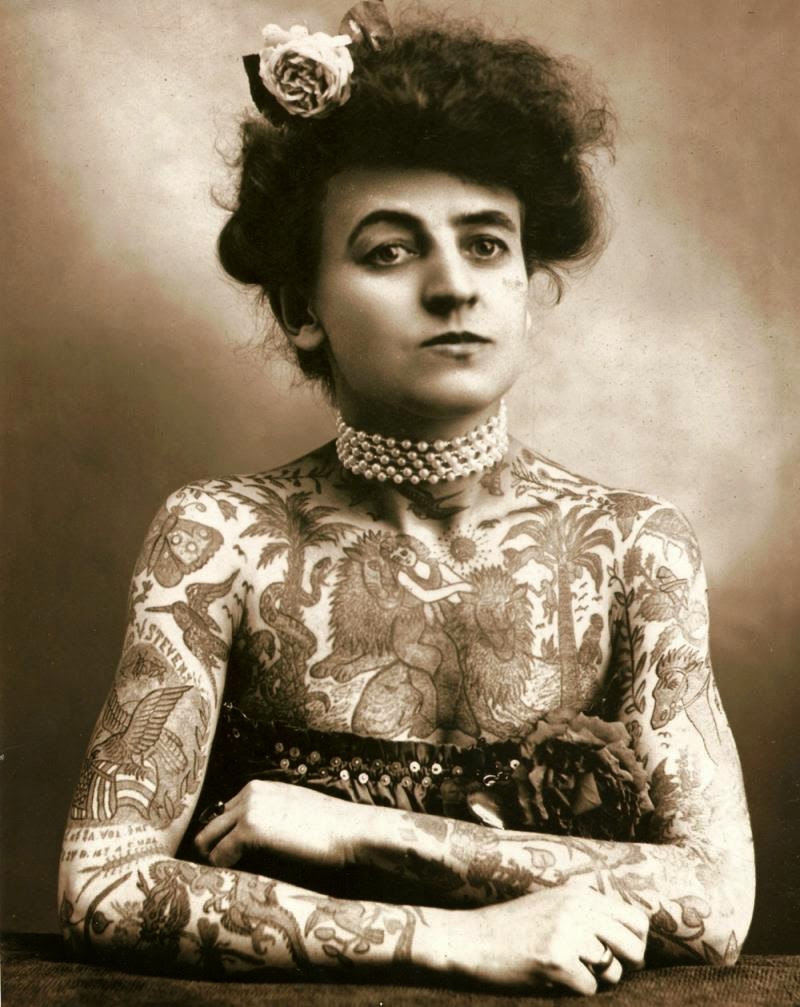

For a certain period of time, it became very hip to think of classic tattoo artist Norman “Sailor Jerry” Collins as the epitome of WWII era retro cool. His name has become a prominent brand, and a household name in tattooed households—or those that watch tattoo-themed reality shows. But I submit to you another name for your consideration to represent the height of vintage rebellion: Maud Wagner (1877–1961).

No, “Maud” has none of the rakish charm of “Sailor Jerry,” but neither does the name Norman. I mean no disrespect to Jerry, by the way. He was a prototypically American character, tailor-made for the marketing hagiography written in his name. But so, indeed, was Maud Wagner, not only because she was the first known professional female tattoo artist in the U.S., but also because she became so, writes Margo DeMello in her history Inked, while “working as a contortionist and acrobatic performer in the circus, carnival, and world fair circuit” at the turn of the century.

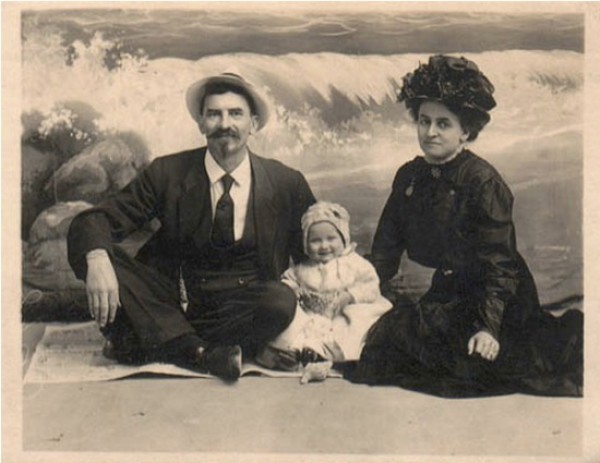

Aside from the cowboy perhaps, no spirit is freer in our mythology than that of the circus performer. The reality of that life was of course much less romantic than we imagine, but Maud’s life—as a side show artist and tattooist—involves a romance fit for the movies. Or so the story goes. She learned to tattoo from her husband, Gus Wagner, an artist she met at the St. Louis World’s Fair, who offered to teach her in exchange for a date. As you can see in her 1907 picture at the top, after giving her the first tattoo, he just kept going (see the two of them above). “Maud’s tattoos were typical of the period,” writes DeMello, “She wore patriotic tattoos, tattoos of monkeys, butterflies, lions, horses, snakes, trees, women, and had her own name tattooed on her left arm.”

Unfortunately there seem to be no images of Maud’s own handiwork about, but her legacy lived on in part because Gus and Maud had a daughter, given the endearing name Lovetta (see the family above), who also became a tattoo artist. Unlike her mother, however, Lovetta did not become a canvas for her father’s work or anyone else’s. According to tattoo site Let’s Ink, “Maud had forbidden her husband to tattoo her and, after Gus died, Lovetta decided that if she could not be tattooed by her father she would not be tattooed by anyone.” Like I said, romantic story. Unlike Sailor Jerry, the Wagner women tattooed by hand, not machine. Lovetta gave her last tattoo, in 1983, to modern-day celebrity artist, marketing genius, and Sailor Jerry protégée Don Ed Hardy.

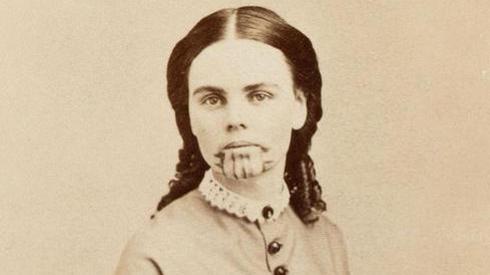

The cultural history of tattooed and tattooing women is long and complicated, as Margot Mifflin documents in her 1997 Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. For the first half of the twentieth century, heavily-inked women like Maud were circus attractions, symbols of deviance and outsiderhood. Mifflin dates the practice of displaying tattooed white women to 1858 with Olive Oatman (above), a young girl captured by Yavapis Indians and later tattooed by the Mohave people who adopted and raised her. At age nineteen, she returned and became a national celebrity.

Tattooed Native women had been put on display for hundreds of years, and by the turn of the 20th century World’s Fair, “natives… whether tattooed or not, were shown,” writes DeMello, in staged displays of primitivism, a “construction of the other for public consumption.” While these spectacles were meant to represent for fairgoers “the enormous progress achieved by the West through technological advancements and world conquest,” another burgeoning spectacle took shape—the tattooed lady as both pin-up girl and rebellious thumb in the eye of imperialist Victorianism and its cult of womanhood.

And here I submit another name for your consideration: Jessie Knight (above, with a tattoo of her family crest), Britain’s first female tattoo artist and also onetime circus performer, who, according to Jezebel, worked in her father’s sharp shooting act before striking out on her own as a tattooist. The Mary Sue quotes an unnamed source who writes that her job was “to stand before [her father] so that he could hit a target that was sometimes placed on her head or on an area of her body.” Supposedly, one night he “accidentally shot Jesse in the shoulder,” sending her off to work for tattoo artist Charlie Bell. As the narrator in the short film below from British Pathe puts it, Knight (1904–1994), “was once the target in a sharp shooting act. Now she’s at the business end of the target no more.”

The remark sums up the kind of agency tattooing gave women like Knight and the independence tattooed women represented. Popular stereotypes have not always endorsed this view. “Over the last 100 years,” writes Amelia Klem Osterud in Things & Ink magazine, “a stigma has developed against tattooed women—you know the misconceptions, women with tattoos are sluts, they’re ‘bad girls,’ just as false as the myth that only sailors and criminals get tattoos.”

Jesse Knight—as you can see from the Pathe film and the photo above from 1951—was portrayed as a consummate professional, and in fact won 2nd place in a “Champion Tattoo Artist of all England” in 1955. See several more photos of her at work at Jezebel, and see a gallery of tattooed—and tattooist—ladies from Mifflin’s book at The New Yorker, including such characters as Botticelli and Michelangelo-tattooed Anna Mae Burlington Gibbons, Betty Broadbent, the tattooed contestant in the first televised beauty pageant, and Australian tattoo artist Cindy Ray, “The Classy Lassy with the Tattooed Chassis.” Now there’s a name to remember.

Related Content:

A Dazzling Gallery of Clockwork Orange Tattoos

Why Tattoos Are Permanent? New TED Ed Video Explains with Animation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness