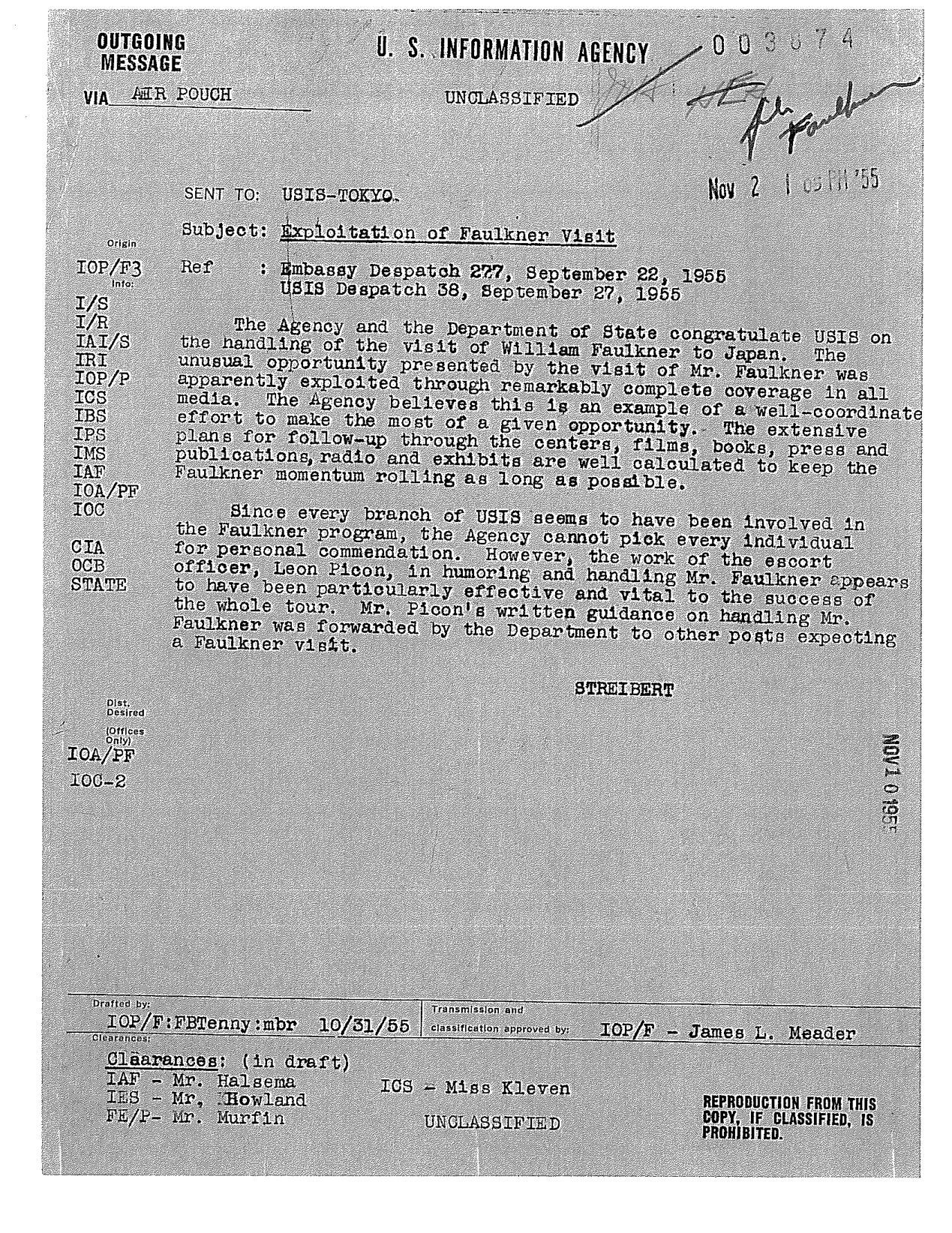

Image by Carl Van Vechten, via Wikimedia Commons

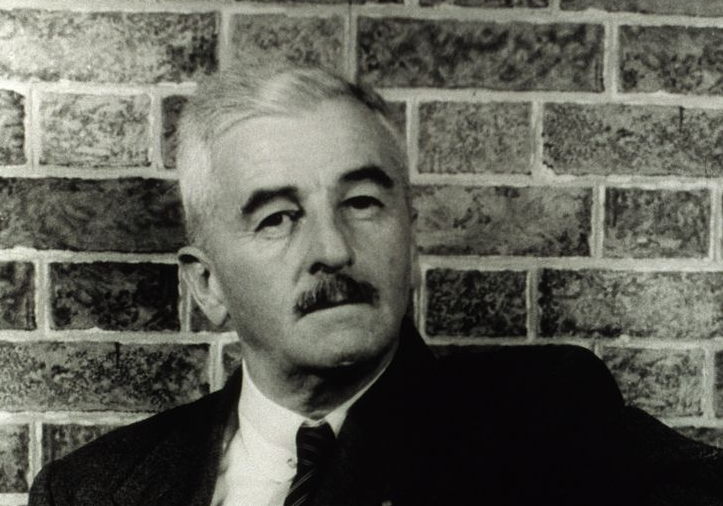

There’s a polite turn of phrase I’ve always found amusing, if a little sad; when someone has too much to drink at a social function and embarrasses him or herself, we say the person has been “overserved.” This euphemism graciously lays the blame at the host’s feet rather than the sometimes shamefaced imbiber’s, suggesting that a good host cares enough about his or her guests—whether they be lightweights or binge-drinking alcoholics—to monitor their intake and keep things on an even keel. In the case of one notoriously hard-drinking guest, novelist William Faulkner, this responsibility became much more than the tactful burden of a few friends. Keeping an eye on the writer’s drinking became a mandate of State Department officers at the U.S. Information Agency during Faulkner’s official trips abroad.

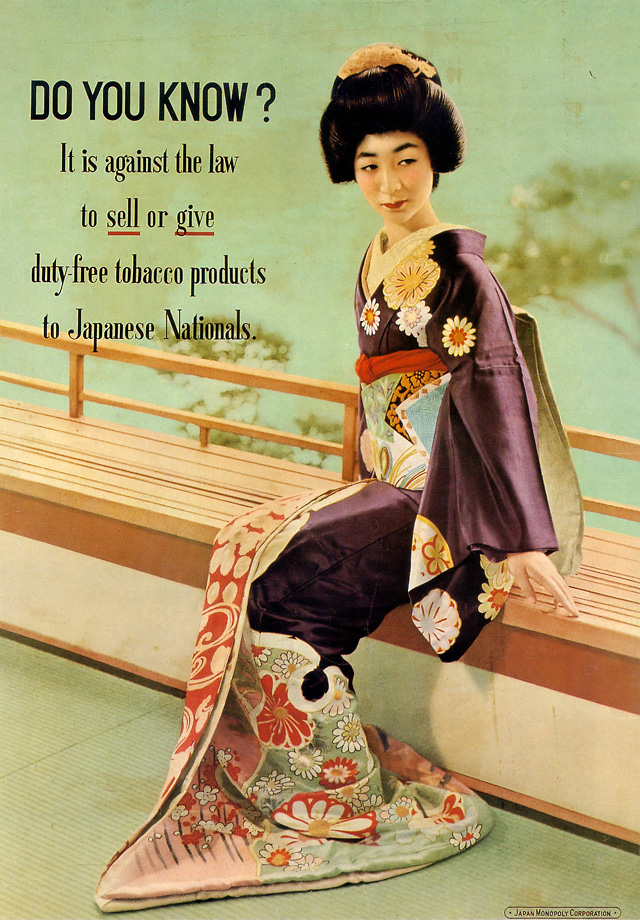

Since his 1950 Nobel win—writes Greg Barnhisel at Slate—Faulkner was in high demand as a Cold War goodwill ambassador for American culture, along with Martha Graham, John Updike, and Louis Armstrong, all “living proof that America wasn’t just Mickey Mouse and chewing gum.” Unfortunately, as most everyone knows, “the author had a bit of a drinking problem.” During a 1955 visit to Japan, for example, he got so drunk at the welcome reception “that the U.S. ambassador ordered he be put on the next plane back to the states.” U.S. officials may have been embarrassed, but the Japanese, it seems, did not feel that Faulkner’s drinking was a hindrance. According to Dr. Leon Picon, books officer at the Tokyo embassy, the writer’s hosts “didn’t see anything wrong with the amount of drink that he had, and they understood when he went off completely, and was not communicable again….” Rather than send Faulkner home, Picon found ways to make sure his guest was never overserved.

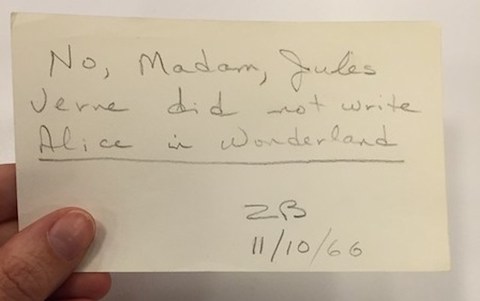

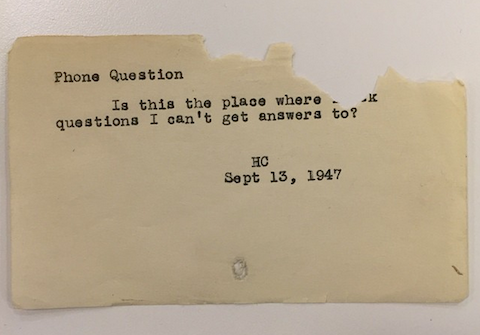

Picon—whom Faulkner called his “wet nurse”—composed and discreetly circulated a document called “Guidelines for Handling Mr. William Faulkner on His Trips Abroad.” These instructions came from Picon’s observations that Faulkner “fared better… when there was little time for concerted drinking.” Of the Japanese visit Faulkner biographer David Mintner writes:

Given shrewdly arranged schedules and carefully arranged audiences, Faulkner talked easily about books, war, and race, hunting, farming, and sailing. Although his manners remained formal and his replies formulaic, he seemed poised and responsive.

Barnhisel quotes among Picon’s guidelines for assuring a smooth visit the following:

- “Keep several pretty young girls in the front two rows of any public appearance to keep his attention up”

- “Put someone in charge of his liquor at all times so that he doesn’t drink too quickly”

- “Do not allow him to venture out on his own without an escort”

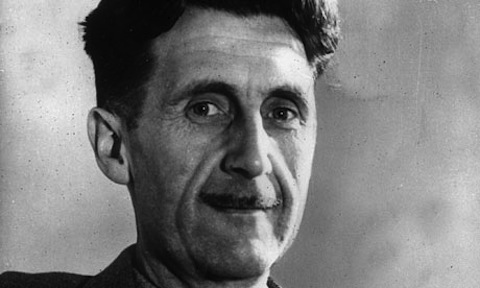

As the declassified memoranda above testify (click once, and then again, to view them in a larger format), the instructions helped other foreign service officers to successfully navigate the writer’s habits. In the memo near the top of the post with the oddly-worded subject “Exploitation of Faulkner Visit,” Dr. Picon is lauded for “humoring and handling Mr. Faulkner,” and his guidelines credited with being “effective and vital to the success of the whole tour.” The memo just above—written in needlessly wordy bureaucratese, apparently by none other than J. Edgar Hoover—commends Picon in more detail:

The Department wishes to commend Mr. Leon Picon for the superb job he did in describing a procedure for developing a program for Mr. Faulkner in other countries.

In his book Cold War Modernists, Barnhisel, a professor at Duquesne University, notes that Faulkner continued to represent the U.S. abroad, in trips to Greece and Venezuela, and though his drinking remained a challenge for his government handlers, the trips were deemed unqualified successes.

Related Content:

Drinking with William Faulkner: The Writer Had a Taste for The Mint Julep & Hot Toddy

Rare Audio: William Faulkner Names His Best Novel, And the First Faulkner Novel You Should Read

William Faulkner Reads His Nobel Prize Speech

Free Online Literature Courses, part of our larger collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness