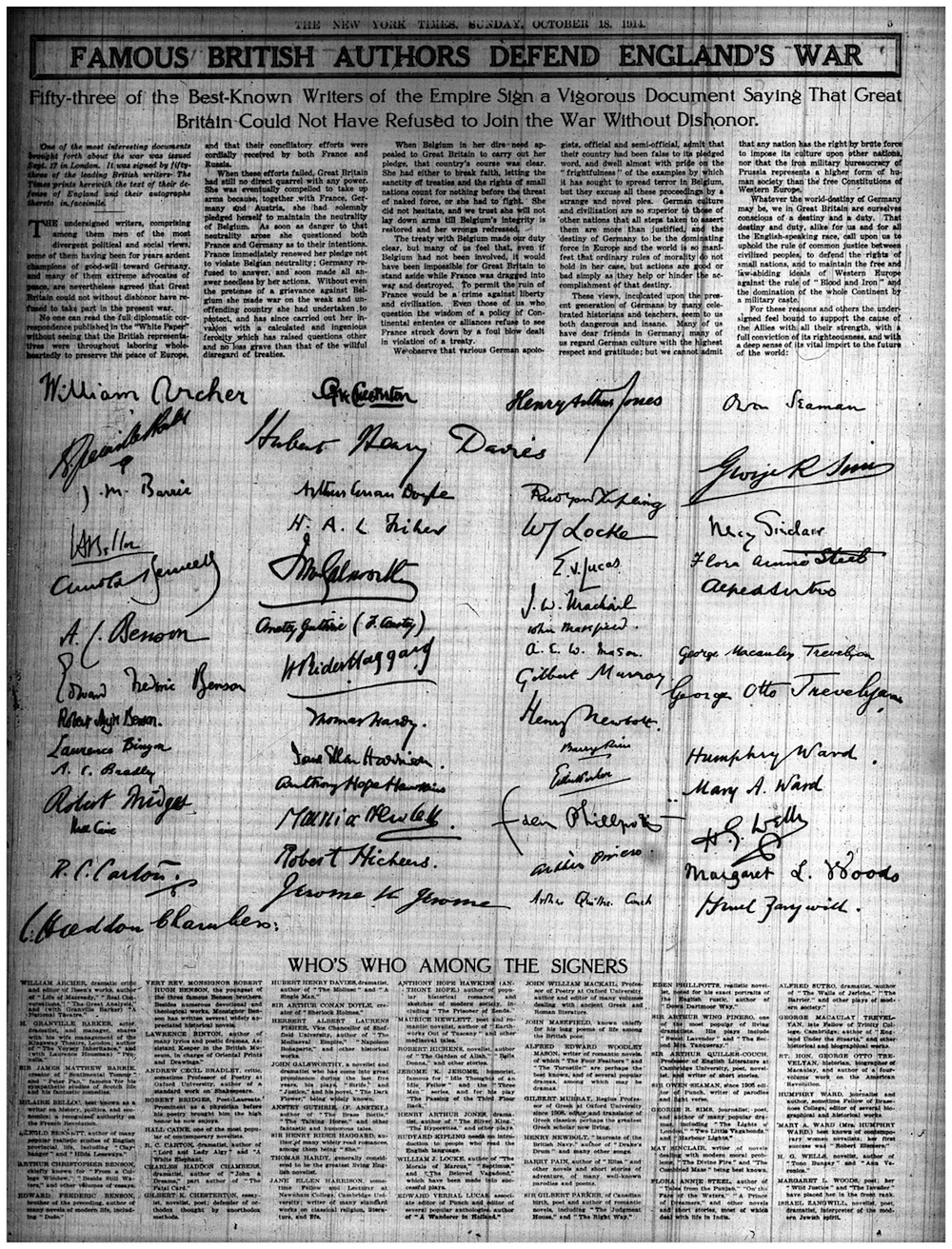

Thinkers have said a great deal about the relative might of the pen and the sword—often one well-known phrase in particular—but still, the subject of intellect versus might remains a matter of active inquiry. But what if might harnesses intellect? What if those who live by the pen pick up their writing tool of choice to endorse the national use of weaponry infinitely more powerful than all the swords ever forged? This very thing happened in the Britain of 1914: “FAMOUS AUTHORS DEFEND ENGLAND’S WAR,” read the headlines, and University of Ottawa English professor Nick Milne has more historical analysis of the event in the first post of “Pen and Sword,” a series focusing on British Propaganda at the open educational resource World War I Centenary: Continuations and Beginnings.

“In September of 1914,” writes Milne in a version of the post up at Slate, “as the armies of Europe were engaged in the Race to the Sea and the stalemate of the trenches loomed, Rudyard Kipling, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and other British authors collaborated on a remarkable piece of war propaganda. Fifty-three of the leading authors in Britain — a number that included Thomas Hardy and H.G. Wells — appended their names to the ‘Authors’ Declaration.’ This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain ‘could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war.’ ” Other men of letters the War Propaganda Bureau could convince to sign on, in addition to Kipling, a fellow rarely called insufficiently patriotic, included “defender of unorthodox thought by unorthodox methods” G.K. Chesterton.

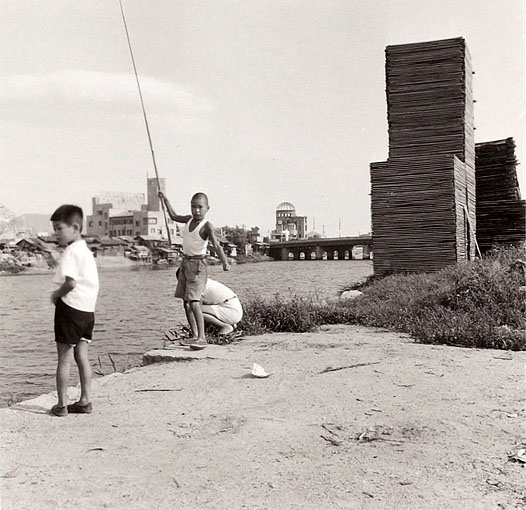

You can take a close-up look at the complete list of signatories with their brief bios, as well as the signatures themselves, by clicking at the image of the New York Times page up above. (Then click again to zoom in.) England may not, in the event, have lost the First World War, but the buoyancy its writers provided its fighting spirit had little to do with it. Germany “responded to the declaration by bringing together an even larger assortment of artists, authors, and scientists to sign the Manifesto of the Ninety-Three, an astounding document which denied any German wrongdoing in Belgium and bewilderingly accused the Allies of ‘inciting Mongolians and negroes against the white race.’ ”

Several of the British writers involved, most notably H.G. Wells, eventually developed a public cynicism toward the war. “The unity of vision and purpose the declaration so strongly implied,” as Milne mildly puts it, “did not endure.”

Related Content:

The First Color Photos From World War I, on the German Front

Watch World War I Unfold in a 6 Minute Time-Lapse Film: Every Day From 1914 to 1918

British Actors Read Poignant Poetry from World War I

Frank W. Buckles, The Last U.S. Veteran of World War I

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.