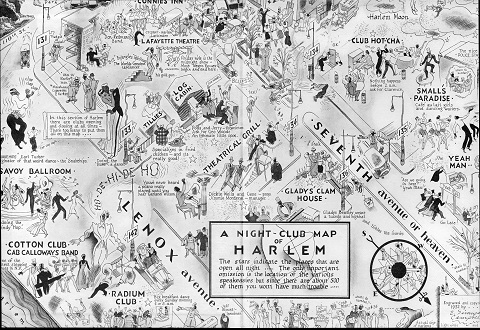

As you might expect from a vicious political movement fronted by a frustrated illustrator, the Nazi party had a complicatedly disdainful yet aspirational — and needless to say, unceasingly fascinating — relationship with art. We previously featured their philistine grudge against modernism that led to the “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937, their mega-budget propaganda film on the Titanic disaster that turned into a disaster itself, and their control-freak list of rules for dance orchestras. The Nazis, as you might expect, didn’t much care for jazz, or at least saw some political capital in openly denouncing it. Yet it seems they also saw some in embracing it, turning the quintessentially free art form toward, as always, their own propagandistic purposes. What if they could come up with their own popular jazz band and, using long-distance short- and medium-wave broadcast signals, turn the Allies’ own music against them? Enter, in 1940, Charlie and His Orchestra. Another Joseph Goebbels creation.

“The idea behind the Nazis’ Charlie campaign,” writes the Wall Street Journal’s Will Friedwald, “was that they could undermine Allied morale through musical propaganda, with a specially devised orchestra broadcasting messages in English to British and American troops.” The groups’ featured singer, “Charlie” himself (real name: Karl Schwedler), would sing not just “irresistible” jazz standards but versions with anti-British, ‑American, and ‑Semitic lyrics. You can hear much of their catalog in the clips here, including what Friedwald cites as their “weirdest recordings”: “Irving Berlin’s ‘Slumming on Park Avenue,’ in which Schwedler, portraying a British pilot with a mock-English accent, sings ‘Let’s go bombing!’ ” and “So You Left Me for the Leader of a Swing Band” refashioned as “So You Left Me for the Leader of the Soviets.” Ultimately, not only did the outside world prove to have better taste than the Nazis, their own fighters did too: “Not only did the Charlie project fail to convert any Allies to the other side, but even Germany’s own troops couldn’t bring themselves to take Nazi swing seriously.” It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing, I suppose — and Charlie and his Orchestra definitely didn’t have it. More audio samples can be heard over at WFMU.

Related Content:

The Nazis’ 10 Control-Freak Rules for Jazz Performers: A Strange List from World War II

The Nazi’s Philistine Grudge Against Abstract Art and The “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.