The work of folklorists and musicologists like Alan Lomax, Stetson Kennedy, and Harry Smith has long been revered in countercultural communities and libraries; and it occasionally reaches mainstream audiences in, for example, the Coen Brother’s 2000 film Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? and its attendant soundtrack, or the playlists of purists on college radio and NPR. But their recordings are much more than historical novelties.

Archives like Lomax’s Association for Cultural Equity—which we’ve featured before—help remind us of our origins as much as bottom-up accounts like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States. Lomax and his colleagues believed that folk art and music infuse and renew “high” art and provide bulwarks against the cynical destitution of mass-market commercial media that can seem so deadening and inescapable.

That is not to say that notions of authenticity aren’t fraught with their own problems of exploitation. Approaching folk art as tourists, we can demean it and ourselves. But the problem is less, I think, one of gentrification than of neglect: it’s simply far too easy to lose touch, a much-remarked-upon irony of the age of social networking. Lomax understood this. He founded ACE “to explore and preserve the world’s expressive traditions with humanistic commitment and scientific engagement.” The organization resides at NYC’s Hunter College and, since Lomax’s retirement in 1996, has been overseen by his daughter, Anna Lomax Wood. Through an arrangement with the Library of Congress, which houses the originals, ACE has access to all of Lomax’s collection of field recordings and can disseminate them online to the public. Lomax’s association has also long been active in repatriating recorded artifacts to libraries and archives in their places of origin, giving local communities access to cultural histories that may otherwise be lost to them.

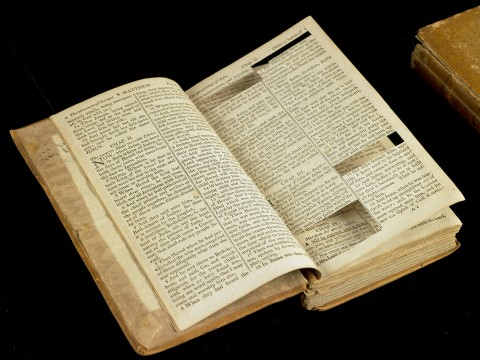

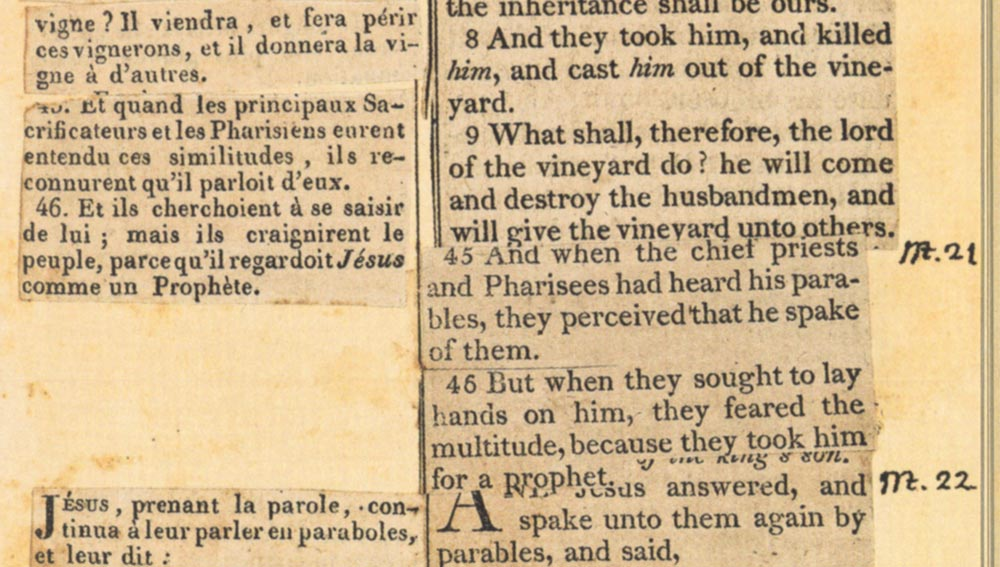

Lomax underscored the significance of his organization’s name in a 1972 essay entitled “An Appeal for Cultural Equity,” in which he lays out the importance of preserving cultural diversity against the “oppressive dullness and psychic distress” imposed upon “those areas where centralized music industries, exploiting the star system and controlling the communication system, put the local musician out of work and silence folk song.” Are we any more improved forty years later for the shocking monopolization of mass media in the hands of a few conglomerates? I’d answer unequivocally no but for one important qualification: mass media in the form of open online archives allows us unprecedented access to, for example, the awesome late-seventies film of R.L. Burnside (top), who like many Mississippi Delta bluesmen before him, would only achieve recognition much later in life. Or we can see native North Carolinian Cas Wallin (above) sing a version of folk song “Pretty Saro” in 1982, a song Bob Dylan recorded and only recently released. Then there’s one of my favorites, “Make Me A Pallet On Your Floor,” picked and sung below by Mississippian Sam Chatmon—a song played and recorded by countless black and white blues and country artists like Mississippi John Hurt and Gillian Welch.

These and thousands of other examples from the ACE archive bring musicologists, historians, folklorists, activists, educators, and everyone else closer to Lomax’s ideal—that we “learn how we can put our magnificent mass communications technology at the service of each and every branch of the human family.” The ACE catalog contains over 17,400 digital files, beginning with Lomax’s first tape recordings in 1946, to his digital work in the 90s. The archive includes songs, stories, jokes, sermons, interviews and other audio artifacts from the American South, Appalachia, the Caribbean, and many more locales. The archive features recordings from famous names like Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly but primarily consists of folk music from anonymous folk, representing a variety of languages and ethnicities. And the archive is ever-expanding as it continues to digitize rare recordings, and to upload vintage film, like the videos above, to its YouTube channel.

Related Content:

Legendary Folklorist Alan Lomax: ‘The Land Where the Blues Began’

Woody Guthrie at 100: Celebrate His Amazing Life with a BBC Film

Hear Zora Neale Hurston Sing the Bawdy Prison Blues Song “Uncle Bud” (1940)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness