So much has been written about hand-written letters, mostly lamenting their death. What else can be added about the beautiful vulnerability of handwriting and the satisfying feel of paper stationary and envelopes, not to mention the miracle of letter delivery? Think of all those heartsick soldiers in wars old and modern receiving an actual letter from home, thousands of miles away.

The only news about letter writing is that we continue to discover its value. Just recently Cambridge University published some 1,200 letters exchanged between Charles Darwin and his closest friend, the botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker. The letters span 40 years of Darwin’s working life, from 1843 to his death in 1882, and join the other letters in the Darwin Correspondence Project.

There is so much to appreciate about these letters. Call it 19th century bromance, if you must, but the correspondence between Darwin and Hooker touched on nearly every subject, scientific and personal. Darwin wrote Hooker for his help negotiating with publishers, for his opinion about whether seeds from islands without four-legged animals are ever hook-shaped, and for his support after his 6‑year-old daughter Maria died.

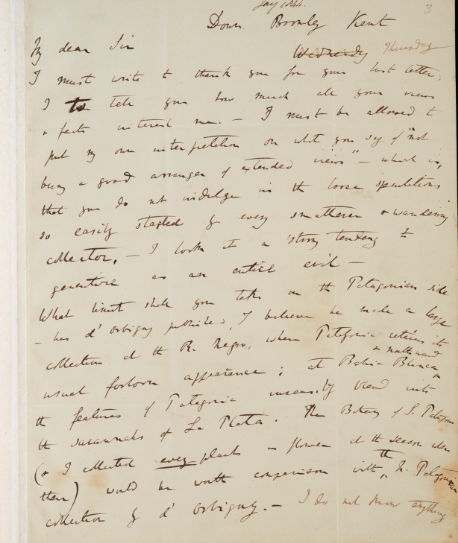

From a scientific point of view the most important letter may be the one Darwin wrote Hooker on January 11, 1844. Writing from his home, Down House in Kent, Darwin fires questions at Hooker about seeds, seashells and Arctic species—his mind obviously a blur of activity—and then describes that his work has taken a “presumptuous” turn. After years of research and collecting specimens, he was beginning to form an idea that “species are not (it is like confessing a murder) immutable.”

Fifteen years later Darwin published On the Origin of Species. (Find it on our Free Audio Books and Free eBooks collections.)

In his letters to Hooker, himself a great botanist and explorer, Darwin works out and worries over his ideas. In one letter he expresses impatience with all other existing explanations for the geographical distribution of plants.

The Correspondence Project has archived more than 7,500 of Darwin’s letters altogether, including the mail he sent home while at sea aboard The Beagle. Darwin was 22 when he joined a team to chart the coast of South America, a trip that was planned for two years but which stretched into five. After a bout of seasickness, Darwin wrote home to his father.

A quick aside to those who long for the days of long letters and who believe that our IQs drop a point with each text: Take note of Darwin’s liberal use of ampersands, numerals and quaint 19th century contractions (sh’d for should, etc.). IMHO, these are all just Victorian shortcuts to speed up the process of handwriting when the mind can work so much more quickly.

Kate Rix writes about education and digital media. Visit her website: .