Perhaps you enjoyed yesterday’s post on Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii but today find yourself unsatisfied, longing for more footage that combines the band with a historically iconic work of architecture. Today, dear readers, we have a concert film that might fit your bill: The Wall — Live in Berlin, viewable free on YouTube. While it features neither the actual Berlin Wall — that had already fallen — nor the complete lineup of Pink Floyd, it compensates with a degree of spectacle that, in terms of human labor, must rank alongside several of the wonders of the ancient world. This live performance of The Wall, Pink Floyd’s driving, paranoid 1979 rock opera, takes place on Potsdamer Platz, nor far from where the Berlin Wall stood a mere eight months before. The show’s crew gradually builds their own wall right there onstage over the course of the show, expressly to suffer the same fate as both the real one that divided East Germany from the West and the metaphorical one that separates The Wall’s disaffected rock-star protagonist from the rest of humanity.

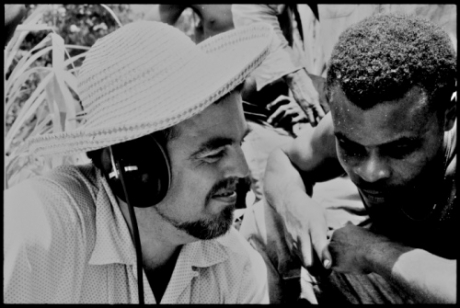

The Wall — Live in Berlin happened not as an official Pink Floyd show, but more as a production by founding member Roger Waters. But you couldn’t accurately call it a Roger Waters solo show either, since, even aside from the large technical staff needed to orchestrate such an event, he enlisted countless guest stars to put their own spin on the songs, including Cyndi Lauper, Van Morrison, Thomas Dolby, Germany’s own Scorpions, and — who could forget? — the band of the Combined Soviet Forces in Germany.

The performance drew hundreds of thousands of viewers, a sight from the stage which must surely have kept Waters wondering, in the following decades, if it might make sense to return to The Wall’s well. But could the show ultimately represent a non-replicable moment in cultural, musical, and political history? Could only the Berlin of July 1990 have seen progressive rockers and pop stars join forces to turn a dark, heady double concept album into one of the most elaborate and well-attended concerts in rock history?

You can find an answer to these questions in Waters’ recent The Wall Live tour, which began in September 2010. The video above captures the show in Melbourne last year. Just as they did not simply stage a live replica of The Wall (the album) for Live in Berlin, Rogers and company have, this time around, wisely chosen not to attempt a recreation of that impressive evening twenty years before. While no less bold and complex than its all-out predecessor, the project of The Wall Live somehow interprets its musical source material in a more subdued and — for lack of a better word — artistic manner. These choices acknowledge the fact that popular music, even as generated by the Lady Gagas of the world, has stepped back from the straightforward spectacle at its height in the late eighties. Understanding, too, that the world-dividing clash between communism and capitalism no longer looms quite so overwhelmingly in the zeitgeist, Waters has updated the new shows with an infusion of his current anti-war views. In Pink Floyd: Live in Pompeii, Waters openly worried about becoming “a relic of the past.” Watch the evolution between these two performances and judge for yourself whether he’s succeeded so far in avoiding it.

H/T goes to Kate for flagging this concert for us…

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.