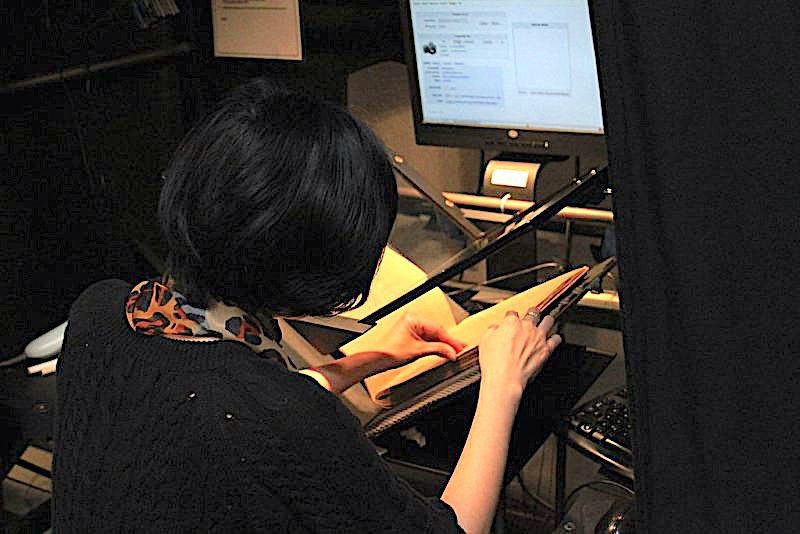

Image by Jason “Textfiles” Scott, via Wikimedia Commons

All books in the public domain are free. Most books in the public domain are, by definition, on the old side, and a great many aren’t easy to find in any case. But the books now being scanned and uploaded by libraries aren’t quite so old, and they’ll soon get much easier to find. They’ve fallen through a loophole because their copyright-holders never renewed their copyright, but until recently the technology wasn’t quite in place to reliably identify and digitally store them.

Now, though, as Vice’s Karl Bode writes, “a coalition of archivists, activists, and libraries are working overtime to make it easier to identify the many books that are secretly in the public domain, digitize them, and make them freely available online to everyone.” These were published between 1923 and 1964, and the goal of this digitization project is to upload all of these surprisingly out-of-copyright books to the Internet Archive, a glimpse of whose book-scanning operation appears above.

“Historically, it’s been fairly easy to tell whether a book published between 1923 and 1964 had its copyright renewed, because the renewal records were already digitized,” writes Bode. “But proving that a book hadn’t had its copyright renewed has historically been more difficult.” You can learn more about what it takes to do that from this blog post by New York Public Library Senior Product Manager Sean Redmond, who first crunched the numbers and estimated that 70 percent of the titles published over those 41 years may now be out of copyright: “around 480,000 public domain books, in other words.”

The first important stage is the conversion of copyright records into the XML format, a large part of which the New York Public Library has recently completed. Bode also mentions a software developer and science fiction author named Leonard Richardson who has written Python scripts to expedite the process (including a matching script to identify potentially non-renewed copyrights in the Internet Archive collection) and a bot that identifies newly discovered secretly public-domain books daily. Richardson himself underscores the necessity of volunteers to take on tasks like seeking out a copy of each such book, “scanning it, proofing it, then putting out HTML and plain-text editions.”

This work is now happening at American libraries and among volunteers from organizations like Project Gutenberg. The Internet Archive’s Jason Scott has also pitched in with his own resources, recently putting out a call for more help on the “very boring, VERY BORING (did I mention boring)” project of determining “which books are actually in the public domain to either surface them on @internetarchive or help make a hitlist.” Of course, many more obviously stimulating tasks exist even in the realm of digital archiving. But then, each secretly public-domain book identified, found, scanned, and uploaded brings humanity’s print and digital civilizations one step closer together. Whatever comes out of that union, it certainly won’t be boring.

Related Content:

11,000 Digitized Books From 1923 Are Now Available Online at the Internet Archive

British Library to Offer 65,000 Free eBooks

Download for Free 2.6 Million Images from Books Published Over Last 500 Years on Flickr

Free: You Can Now Read Classic Books by MIT Press on Archive.org

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.