The term free jazz may have existed before Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come arrived in 1959. Yet, however innovative the modal experiments of Coltrane or Davis, jazz still adhered to its most fundamental formulas before Coleman. “Conventional jazz harmony is religiously chord-based,” writes Josephine Livingstone at New Republic, “with soloists improvising within each key like balls pinging through a pinball machine. Coleman, in contrast, imagined harmony, melody, and rhythm as equal constituents.”

This philosophy, jazz critic Martin Williams wrote upon hearing Coleman’s debut, was necessary to free jazz from its formal constraints. “Someone had to break through the walls that those harmonies have built and restore melody.” Melody was everything to Coleman—even drummers can play like melodic instrumentalists. In a 1987 interview, he described how Ed Blackwell “plays the drums as if he’s playing a wind instrument. Actually, he sounds more like a talking drum. He’s speaking a certain language that I find is very valid in rhythm instruments.”

Coleman connected his musical theory back to the origins of rhythmic music: “the drums, in the beginning, used to be like the telephone—to carry the message.” Interviewer Michael Jarrett ventures that Coleman’s ensemble recordings are more like a “party line,” to which the saxophonist agrees. Music, he believed, was a radically democratic—“beyond democratic”—form of communication. “If you decided to go out today and get you an instrument,” he says, “and do whatever it is that you do, no one can tell you how you’re going to do it but when you do it.”

This approach seemed irresponsible to many of Coleman’s peers. Alto saxophonist Jackie McLean described the general reaction as “spend[ing] your whole life making a three-piece suit that’s incredible, and this guy comes along with a jumpsuit, and people find that it’s easier to step into a jumpsuit than to put on three pieces.” Collective improvisation, however, cannot in any way be described as “easy,” and Coleman was a brilliant player who could do it all.

“I could play and sound like Charlie Parker note-for-note,” he has said, “but I was only playing it from method. So I tried to figure out where to go from there,” Loosening the constrictions did not mean that Coleman lacked “requisite virtuosity,” as Maria Golia writes in a new Coleman biography. Instead, he “proposed an alternative means for its expression.” (In Thomas Pynchon’s V, a character says of a Coleman-like saxophonist, “he plays all the notes Bird missed.”) This emerged in experimental improvisations like 1961’s landmark Free Jazz, an album that “practically defies superlatives in its historical importance,” Steve Huey writes at Allmusic.

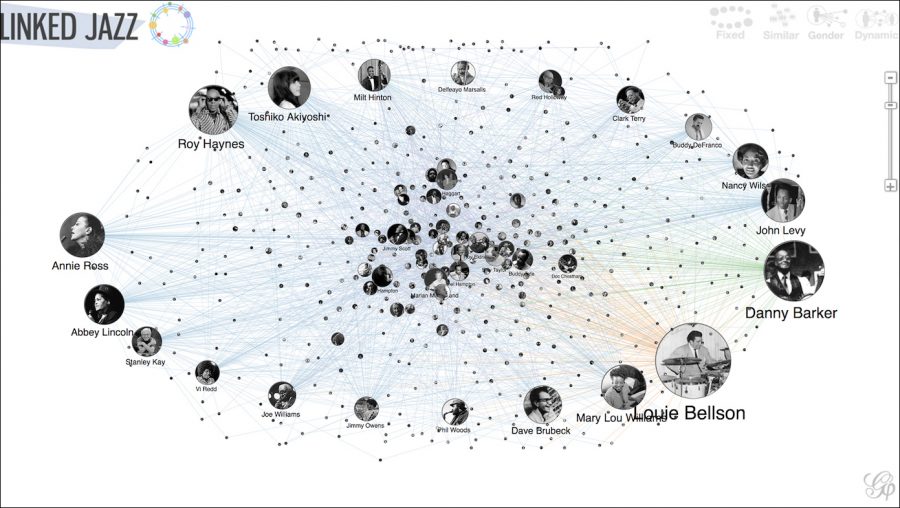

The album features players like Blackwell, Don Cherry, and Eric Dolphy in a “double-quartet format,” with two rhythm sections playing simultaneously, one on the right stereo channel, one on the left. Composed on the spot, “there was no road map for this kind of recording.” But there was a theory that held it all together. Coleman eventually called the theory “Harmolodics,” a word that sums up his ideas about the equality of rhythm, harmony, and melody—a compositional method that freed jazz from its dependence on European forms and returned it, in a way, to its roots in a call-and-response tradition.

Coleman described his long-simmering ideas in a 1983 manifesto titled “Prime Time for Harmolodics.” The title references the band, Prime Time, he formed in 1975 that featured two bassists, two guitarists, and—like his ensemble on Free Jazz, or like the Grateful Dead—two drummers. Jerry Garcia joined the band for its 1988 album Virgin Beauty, expanding Coleman’s fanbase—already significant in various rock circles—to Deadheads. (See Prime Time in Germany in 1981 below.) Harmolodic playing could be dissonant, atonal, and cacophonous, and it could be sublime, often in the same moment.

Simultaneity, radical democracy, intimate communication—these were the principles of “unison” that Coleman found essential to his improvisations.

Question: “Where can/will I find a player who can read (or not read) who can play their instrument to their own satisfaction and accept the challenge of the music environment?” For Harmolodic Democracy — the player would need the freedom to express what Harmolodic information they found to work in composed music. There is always a rhythm — melody — harmony concept. All ideas have lead resolutions. Each player can choose any of the connections from the composers work for their personal expression, etc. Prime Time is not a jazz, classical, rock or blues ensemble. It is pure Harmolodic where all forms that can, or could exist yesterday, today, or tomorrow can exist in the now or moment without a second.

In harmolodic improvisation musicians contribute equally on their own terms, Coleman believed. “From Ornette’s point of view,” writes Robert Palmer in liner notes to the Complete Atlantic Recordings, “each contribution is equally essential to the whole. One tends to hear the horn player as a soloist, backed by a rhythm section, but this is not Coleman’s perspective. ‘In the music we play,’ he said of the performances collected in this box, ‘no one player has the lead. Anyone can come out with it at any time.’ ” Jerry Garcia remembers feeling confused when first recording with the saxophonist. “Finally,” says Garcia, “he said, ‘Oh, just go ahead and play, man.’ And I thought, ‘Oh, I get it now.’”

But of course, Garcia was the kind of musician who could “just go ahead and play.” This was the essential element, and it was here, perhaps, that Coleman differed least from his fellow jazz artists—in his sense of having just the right ensemble. “You really have to have players with you who will allow your instincts to flourish in such a way that they will make the same order as if you had sat down and written a piece of music,” he writes. “To me, that is the most glorified goal of the improvising quality of playing – to be able to do that.”

In “harmolodic democracy” no one ever takes the lead, or not for long, and there are no “sidemen.” Rather than following a chord chart or bandleader, the musicians must all listen closely to each other. Conventional riffs and progressions pop up, only to veer wildly in unexpected directions. “Its clear that [harmolodics] is based on taking motifs,” says avant-garde guitarist Marc Ribot, “and freeing it up to become polytonal, melodically and rhythmically.” Rather than abandoning form, Coleman invented new ways to compose and new ways, he wrote, to play.

I was out at Margaret Mead’s school and was teaching some kids how to play instantly. I asked the question, ‘How many kids would like to play music and have fun?’ And all the little kids raised up their hands. And I asked,‘Well, how do you do that?’ And one little girl said, ‘You just apply your feelings to sound.’ She was right — if you apply your feelings to sound, regardless of what instrument you have, you’ll probably make good music.

Coleman formed a label called Harmolodic in 1995 with his son and drummer Denardo. In 2005, he recorded the live album Sound Grammar in Germany, which would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize two years later. The record became the first release on his new label, also called Sound Grammar, and represented a refinement of the harmolodic theory, now called “sound grammar,” in which Coleman re-emphasizes the importance of music as the ur-form of human communication. “Music,” he says, “is a language of sounds that transforms all human languages.”

Related Content:

How Ornette Coleman Shaped the Jazz World: An Introduction to His Irreverent Sound

Philosopher Jacques Derrida Interviews Jazz Legend Ornette Coleman: Talk Improvisation, Language & Racism (1997)

When Jazz Legend Ornette Coleman Joined the Grateful Dead Onstage for Some Epic Improvisational Jams: Hear a 1993 Recording

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.