My kids used to beg their dad to help out with their impromptu puppet shows. He complied by having our daughter’s favorite baby doll deliver an interminable curtain speech, hectoring the audience (me) to become subscribers and make donations via the small envelope they’d find tucked in their programs.

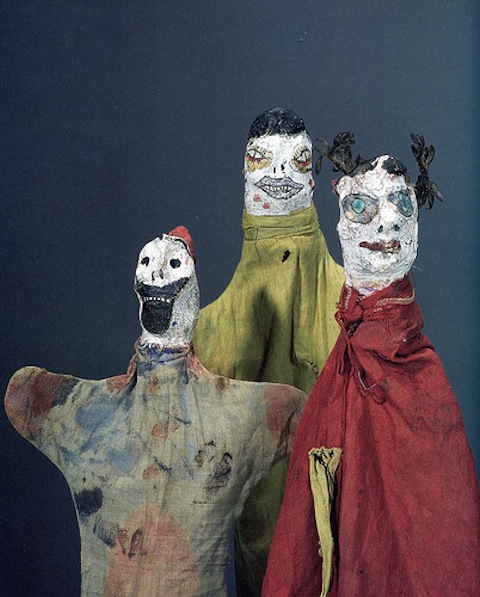

Like my husband, artist Paul Klee (1879–1940) loomed large in his child’s early puppet work. To mark his son Felix’s ninth birthday, Klee fashioned eight hand puppets based on stock characters from Kasperl and Gretl — Germany’s answer to Punch and Judy. The boy took to them so enthusiastically that his dad kept going, creating something in the neighborhood of fifty puppets between 1916 and 1925. The cast soon expanded to include cartoonish political figures, a self-portrait, and less recognizable characters with a decidedly Dada-ist bent. Klee also fixed Felix up with a flea market frame that served as the proscenium for the shows he put on in a doorway of the family’s tiny apartment.

When Felix set out into the world at the age of eighteen, he packed his favorite childhood puppets, while his dad hung onto the ones born of his years on the faculty of the Bauhaus. Felix’s portion of the collection was almost entirely destroyed during the bombing of Wurzburg in World War II. Dr. Death was the only member of the original eight to escape unscathed.

You can find a gallery of Klee’s puppets here, and a book dedicated to Klee’s puppetry here.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Tchaikovsky Puppet in Timelapse Film

Puppet Making with Jim Henson: A Priceless Primer from 1969

Bauhaus, Modernism & Other Design Movements Explained by New Animated Video Series

Free: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim Offer 474 Free Art Books Online

Ayun Halliday is okay with puppets as long as she can hold them at arm’s length. Follow her @AyunHalliday