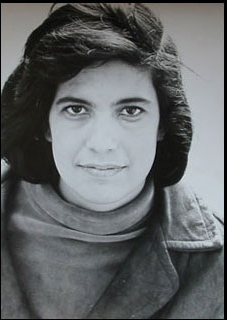

After half a century and 31 books, Philip Roth casually announced last month in an interview with a French magazine that he was calling it quits. He actually made the decision back in 2010, after the publication of his Booker Prize-winning novel Nemesis. “I didn’t say anything about it because I wanted to be sure it was true,” the 79-year-old Roth told New York Times reporter Charles McGrath last week in what he said would be his last interview. “I thought, ‘Wait a minute, don’t announce your retirement and then come out of it.’ I’m not Frank Sinatra. So I didn’t say anything to anyone, just to see if it was so.”

Although Roth had been privately telling friends about his retirement for two years, according to David Remnick in The New Yorker, the public announcement came as a shock for many. From his 1959 National Book Award-winning debut Goodbye, Columbus and Five Short Stories and his outrageously funny 1969 classic Portnoy’s Complaint through his remarkably prolific late period, with its steady stream of beautifully crafted novels like Operation Shylock, Sabbath’s Theater and The Human Stain, it seemed as though Roth had the creative energy to keep writing until he took his last breath.

But perhaps if we’d paid closer attention we wouldn’t be so surprised. In this 2011 video, for example, which shows Roth reading a few pages from Nemesis after it won the Man Booker International Prize, he basically says it: “Coming where they do, they’re the pages I like best in Nemesis. They constitute the last pages of the last work of fiction I’ve published–the end of the line after 31 books.”

Related content:

Philip Roth’s Creative Surge and the Death of the Novel

Philip Roth Predicts the Death of the Novel; Paul Auster Counters