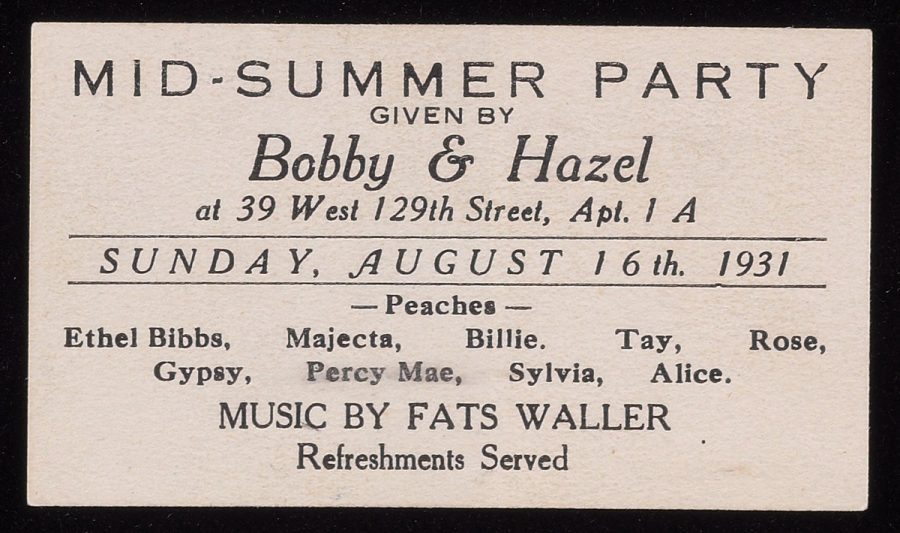

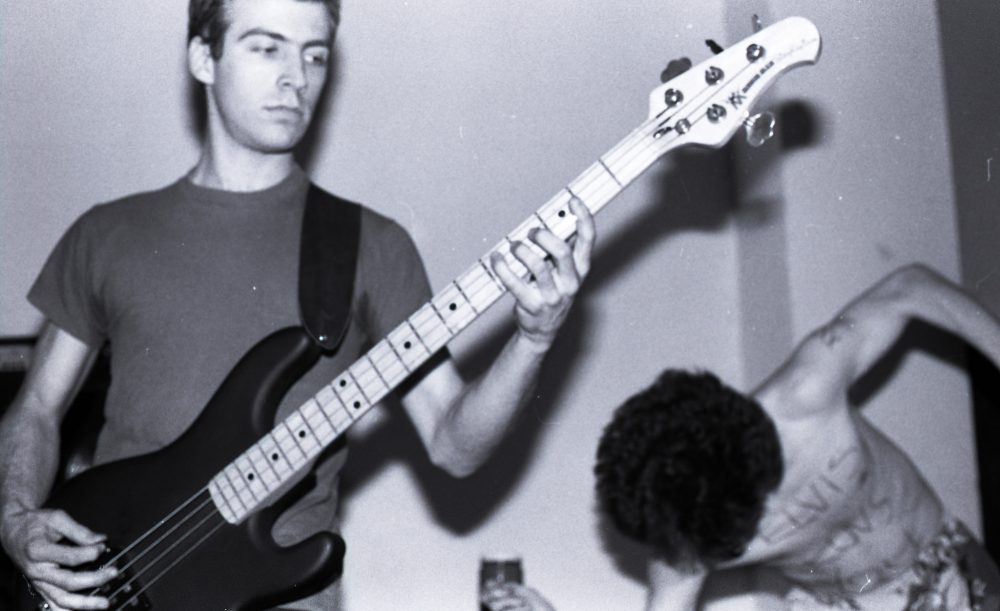

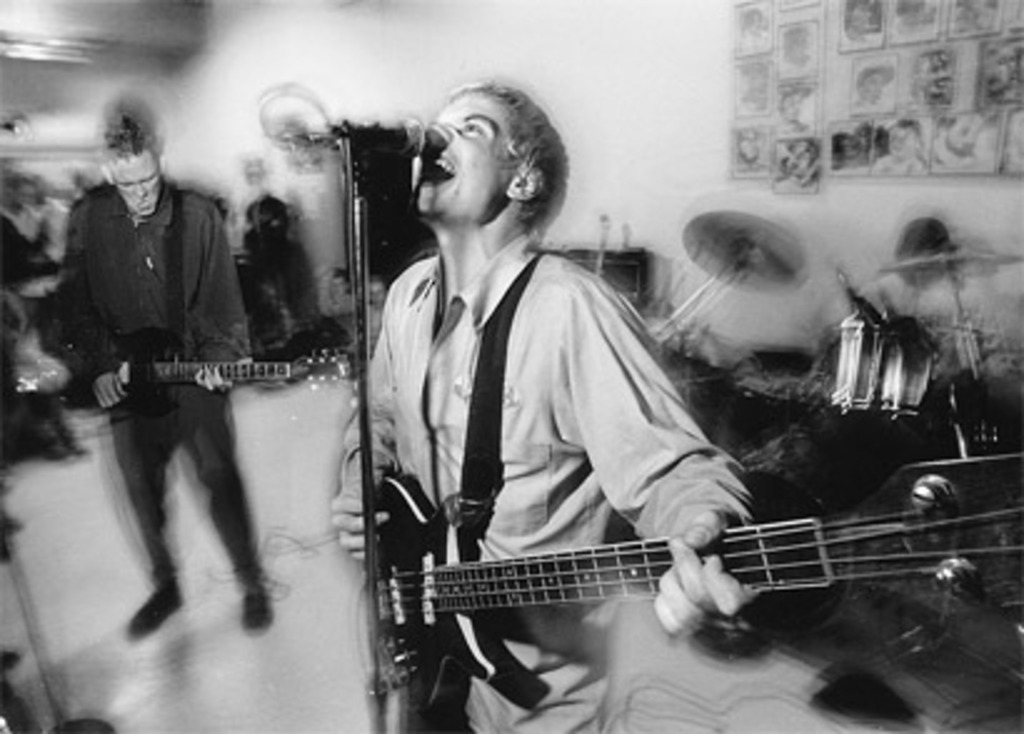

Image of Fugazi by Brad Sigal, via Flickr Commons

Apart from whatever political nightmare du jour we’re living in, it can be easy to dislike Washington, DC. I say this as someone who grew up outside the city, called it home for many years, and generally found its public face of monuments, tourists, politicos, and waves of lobbyists and bureaucrats pretty alienating. The “real” DC was elsewhere, in the city’s historic Black neighborhoods, many now heavily gentrified, which hosted legendary jazz clubs and gave birth to the genius of go-go. And even in the privileged, middle class neighborhoods and DMV suburbs. Among the skate punks and disaffected military brats who created the DC punk scene, a seething, furiously productive punk economy centered around Dischord Records. The small label has been as hugely influential in the past few decades as Seattle’s Sub Pop or Long Beach’s SST.

Formed in 1980 by Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye and his bandmate Jeff Nelson, Dischord is 6 years older than Sub Pop and in several ways it inspired a template for the West Coast. Dave Grohl came from the DC Punk scene, as did Black Flag’s Henry Rollins. Rollins and MacKaye were childhood friends and DC natives, and MacKaye went on to form Fugazi, virtually a DC institution for well over a decade.

MacKaye’s brother Alec was a member of Dischord band Faith—one of Kurt Cobain’s admitted influences—and of Ignition with Gray Matter’s Dante Ferrando, who went on, with investments from Dave Grohl, to found the club Black Cat, a central hub of punk and indie rock in DC for 27 years. The more you dig into the musical families of Dischord, the more you see how embedded they are not only in their home city, but in the weft of modern American rock.

Dischord has been celebrated in gallery exhibitions, the hip documentary Salad Days, and the short An Impression: Dischord Records (watch here). Now they’ve released their catalog to stream for free at Bandcamp. The slew of bands featured offers a gallery of nostalgia for a certain brand and vintage of DC native. And it offers a pristine opportunity to get caught up if you don’t know Dischord bands.

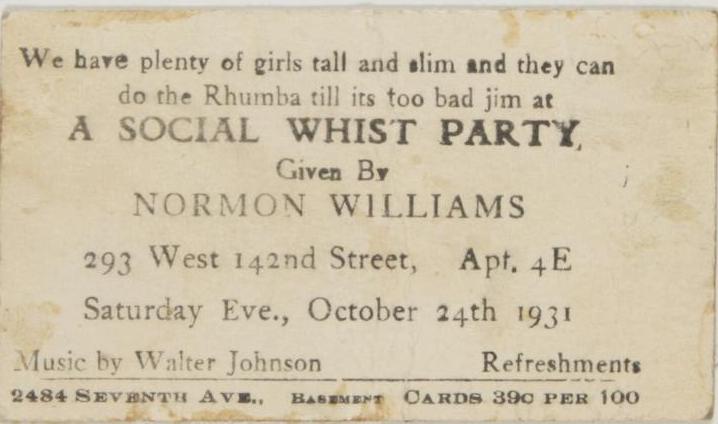

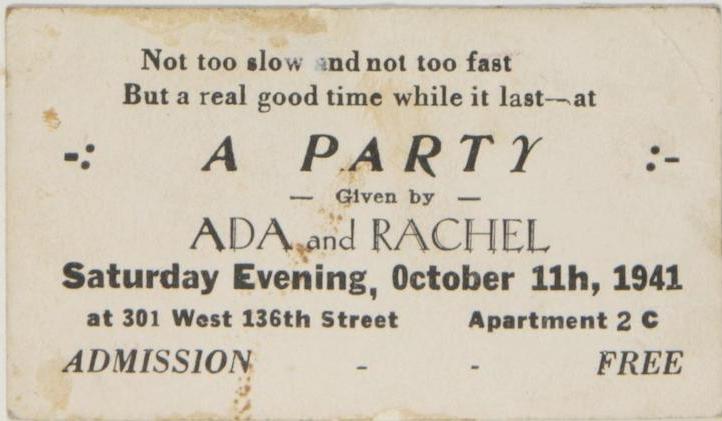

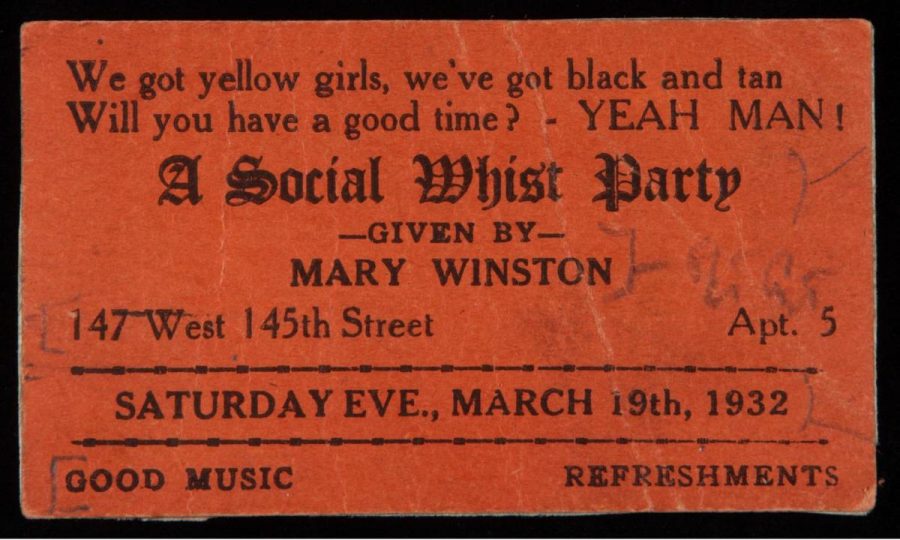

Image of Hoover by Dischord Records, via Wikimedia Commons

The common features of its lineup—political urgency, earnestness, melodic experimentation, unpretentiousness—stand out. Dischord bands could be math‑y and technical, straight edge, vegan, Buddhist, Hare Krishna, fiercely feminist, anti-capitalist, and anti-war.… These may not sound like the makings of a great party scene, but they made for a committed cadre of hard working musicians and a wide circle of dedicated fans around the country who have kept the label thriving in its way.

What distinguishes Dischord from its more famous peers is the fact that it only releases bands from the DC area. Why? “Because this is the city where we live, work, and have the most understanding,” they write on their site. Still, given the label’s heightened profile in recent years, it’s surprising that so much of its music remains unknown outside of a specific audience. Fugazi is the best-known band on the roster, and for all their major critical importance, they have kept a fairly low profile. But this is the spirit of the label, whose founders wanted to make music, not make stars. Bands like Shudder to Think and Jawbox may have eventually moved to bigger labels, but they did their best work with Dischord.

Dag Nasty, Embrace, Government Issue, Make-Up, Q and Not U, Rites of Spring, Soulside, Void, Untouchables, Slant 6, the Nation of Ulysses.… these are bands, if you don’t know them, you should hear, and already have, in some way, through their enormous influence on so many others: not only Nirvana, but also a contingent of derivative emo bands some of us might prefer to forget. Still the label’s history should not be taken as the gospel canon of DC punk. One of the most influential of DC punk bands, Bad Brains, came out of the jazz scene, invented a blistering mashup of punk and reggae, and get credit for creating hardcore and inspiring Rollins, MacKaye, and their friends. But Bad Brains was “Banned in DC” in 1979, shut out of the clubs. They moved to New York and eventually signed with SST.

Other parts of the scene scorned the clean-living moralism of Dischord, and the label’s sober founders later found themselves “alienated by the violent, suburban, teenage machismo they now saw at their shows,” writes Jillian Mapes at Flavorwire. Dischord became known for championing causes on the left, a legacy that is inseparable from its legend. Not everyone loved their politics, as you might imagine in a city with as many conservative activists and political aspirants as DC. “Great political punk bands—like Priests—still exist in DC,” writes Mapes—and Dischord continues to release great records—“but the ‘80s scene retains its place in history as the pinnacle of political American hardcore music.” And Dischord remains a sometimes unacknowledged legislator of American punk rock in the ‘80s and ’90s. Stream their whole catalog at Bandcamp. You can also download tracks for a fee.

Related Content:

The History of Punk Rock in 200 Tracks: An 11-Hour Playlist Takes You From 1965 to 2016

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness