The last four weeks have seen thousands of tributes to rocker David Bowie.

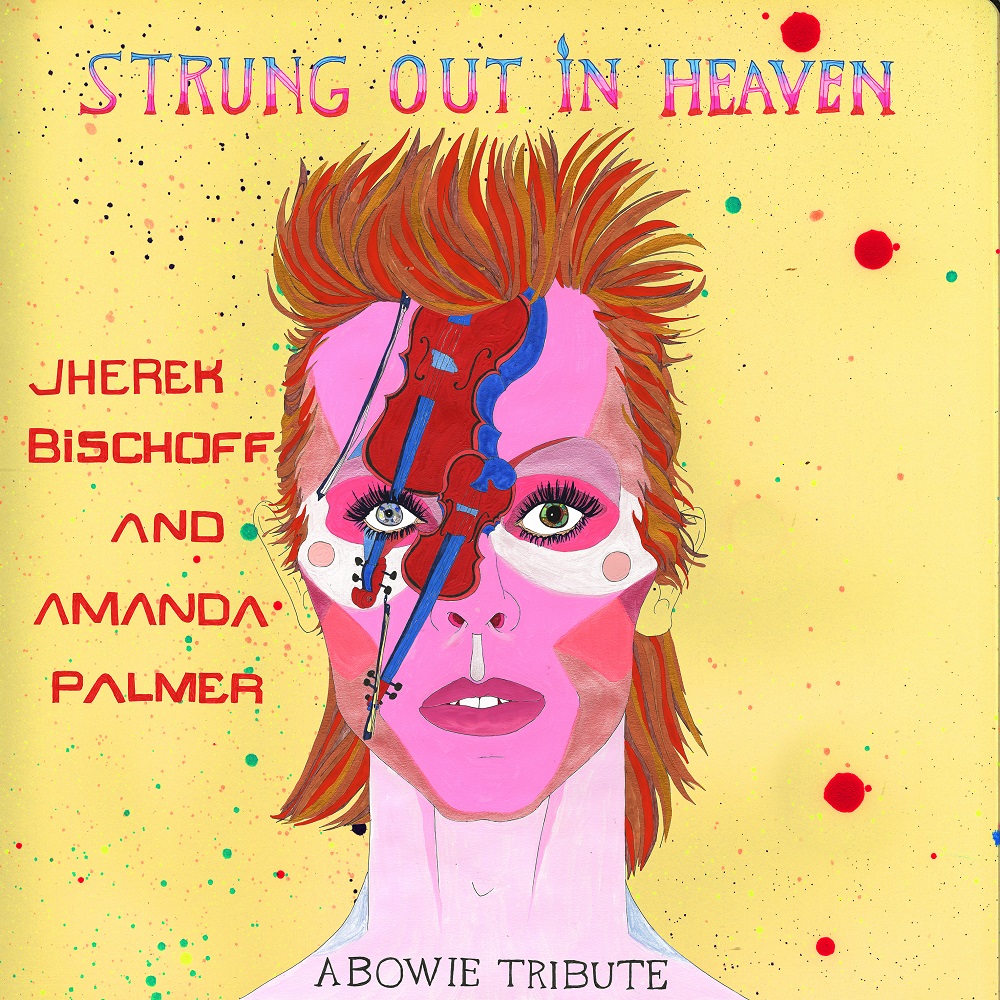

Strung Out In Heaven: A Bowie String Quartet Tribute by Amanda Palmer and her Theatre is Evil collaborator, pop polymath Jherek Bischoff, is both gorgeous and ambitious.

It came together quickly. Bischoff arranged the album’s five tracks and spent three and a half hours recording the strings (Serena McKinney and Alyssa Park on violin, Ben Ullery on viola, and Jacob Braun on cello).

Meanwhile new mother Palmer lined up three days worth of babysitting in order to dive back into the studio. She also tapped some famous friends, who contributed in smaller ways.

The recording, coordination, guest appearances… and babysitting were financed by a stockpile from Palmer’s 7000-some supporters on the crowdfunding site Patreon.

It doesn’t sound like a whip out.

Here’s Palmer’s husband, author Neil Gaiman, counting down to lift-off on “Space Oddity:

And writer/director John Cameron Mitchell, who recorded the “Heroes” call and response on an iPhone in his apartment…

…and channeled Hedwig for the German version:

Gaiman questioned Palmer’s choice to lead with the title track of Bowie’s final album, but as she told New Musical Express, a lot of freshly minted millennial Bowie fans among her Patreon supporters listed “Blackstar” as a favorite. Singer Anna Calvi duets and plays guitar on this stripped down version:

Each tune is matched to a Bowie-centric image by a visual artist. On Palmer’s Patreon blog,“Blackstar” artist, elementary school teacher, and cancer survivor Cassandra Long writes about discussing Bowie’s death with a roomful of kindergarteners. Palmer plans to provide a similar platform to the other participating artists in the days to come.

The finished product is both professional and a labor of love.

Music is the binding agent of our mundane lives. It cements the moments in which we wash the dishes, type the resumes, go to the funerals, have the babies. The stronger the agent, the tougher the memory, and Bowie was NASA-grade epoxy to a sprawling span of freaked-out kids over three generations. He bonded us to our weird selves…Bowie worked on music up to the end to give us a parting gift. So this is how we, as musicians, mourn: keeping Bowie constantly in our ears and brains.

— Amanda Palmer

The complete tracklist is below. You can listen for free, but an ante-up will help Palmer cover 9¢ in licensing fees every time one of the songs is streamed. Any leftover proceeds from sales through March 5th will be donated to Tufts Medical Center’s cancer research wing in memory of David Bowie.

01 “Blackstar” featuring Anna Calvi

02 “Space Oddity” featuring Neil Gaiman

03 “Ashes to Ashes”

04 “Heroes” featuring John Cameron Mitchell

05 Helden” featuring John Cameron Mitchell

06 “Life on Mars?”

Related Content:

David Bowie (RIP) Sings “Changes” in His Last Live Performance, 2006

Amanda Palmer Animates & Narrates Husband Neil Gaiman’s Unconscious Musings

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday