There’s not much left to say about Jimi Hendrix’s last days. The endless stream of commentary surrounding his life and death threatens to bury the man and his music in music-press fetishization, urban legend, and fawning mythology. When I’m able to totally tune out the hype, Hendrix’s polished work stands the time-test, and some of the more raw releases—the bootlegs and demos that appear every few years—at least document musical roads not taken and preserve moments of stunning genius, if not fully-realized compositions.

And Hendrix’s intriguing persona—revealed in casual interviews and conversations—still captivates, with his offhand lyricism and fractal imagination, qualities on full display in his final press interview, to NME’s Keith Altham, on September 11, 1970, just seven days before the artist’s death. (Listen to the YouTube audio above, or Soundcloud below.) Hendrix is breezy, contemplative, a little evasive, revealing his own sense of being between things, not sure where he’s headed next. As all those late-Hendrix bootlegs and demos testify, he could have done anything and made it work with the right band and a bit more time…

But enough what-ifs. Nobody’s better on Hendrix than Hendrix, so listen to the interview. You can find a full transcript and much more Hendrix-on-Hendrix and music-press chatter in a recent (and quite inexpensive) Kindle publication called Jimi Hendrix: Interviews and Reviews 1967–71. Ultimate Classic Rock calls the final interview the “most interesting thing about the book from a historical standpoint,” and this may be true.

Finally, if you don’t make it all the way to the end of the audio, Hendrix leaves on this vivid and quite funny note:

ALTHAM: Do you feel personally that you have enough money to live comfortably without necessarily making more as a sort of professional entertainer?

HENDRIX: Ah, I don’t think so, not the way I’d like to live, because like I want to get up in the morning and just roll over in my bed into an indoor swimming pool and then swim to the breakfast table, come up for air and get maybe a drink of orange juice or something like that. Then just flop over from the chair into the swimming pool, swim into the bathroom and go on and shave and whatever.

ALTHAM: You don’t want to live just comfortably, you wanna live luxuriously?

HENDRIX: No! Is that luxurious? I was thinking about a tent, maybe, [laughs] overhanging … overhanging this … a mountain stream! [laughter].

Related Content:

Watch Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Voodoo Chile’ Performed on a Gayageum, a Traditional Korean Instrument

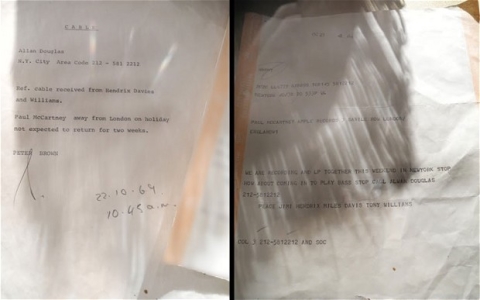

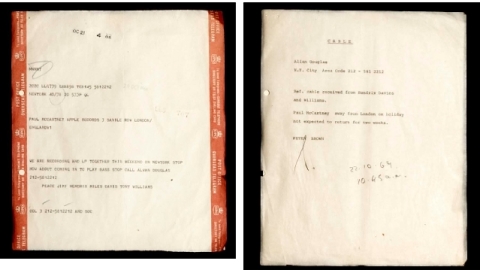

In 1969 Telegram, Jimi Hendrix Invites Paul McCartney to Join a Super Group with Miles Davis

Previously Unreleased Jimi Hendrix Recording, “Somewhere,” with Buddy Miles and Stephen Stills

See Jimi Hendrix’s First TV Appearance, and His Last as a Backing Musician (1965)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness.