Johnny Cash once called 1968 the happiest year of his life. It was the year his masterpiece At Folsom Prison came out, the year he was named the Country Music Association’s Entertainer of the Year, and the year he married the love of his life, June Carter. So it was a fortunate time for a young filmmaker named Robert Elfstrom to meet up with Cash for the making of a documentary.

Elfstrom traveled with Cash for several months in late 1968 and early 1969. The resulting film, Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music, is a revealing look at Cash, his creative process and his ties to family. Elfstrom followed along on a tour that took Cash and his group (including, at different times, Chet Atkins and the Carter Family singers) to a wide range of places, including a prison, an Indian reservation and Cash’s own native soil in the American South. Cash and Carter visit his parents and other family members, and in one moving scene Cash returns to his abandoned childhood home in Dyess, Arkansas, a cotton farming town that was created under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program in the 1930s to give poor families a chance to start over.

The film gives some sense of the complexity of Cash’s personality. There is one scene near the beginning, for example, in which Cash goes hunting and wounds a crow. He then cradles the injured bird in his hands and talks friendly to it. “That scene, to me, says a lot about who Johnny Cash is,” Elfstrom told PBS in a 2008 interview. “John was not always warm and fuzzy like a panda bear all the time. He’s like that part of the time, but he also has a sharp edge and steeliness to him.” Elfstrom went on to describe the situation:

One day, we were hanging out in his house, and he said, “I want to go hunting.” He grabbed his shotgun and was walking through the land around his house when he spied a crow and whipped off a shot. John was a dead shot, so he wounded the crow, and the bird hit the ground. When he picked up the crow, you could feel that something was going through John’s head; he’d almost killed something that maybe he shouldn’t have, and he felt badly about it, but that instinct to hunt and wound was a part of him too. So John carried the crow and sat down in the shade, and I could see he was kind of pissed off at himself. I kept some distance from him, and the next thing I knew, he was writing a song to the crow.

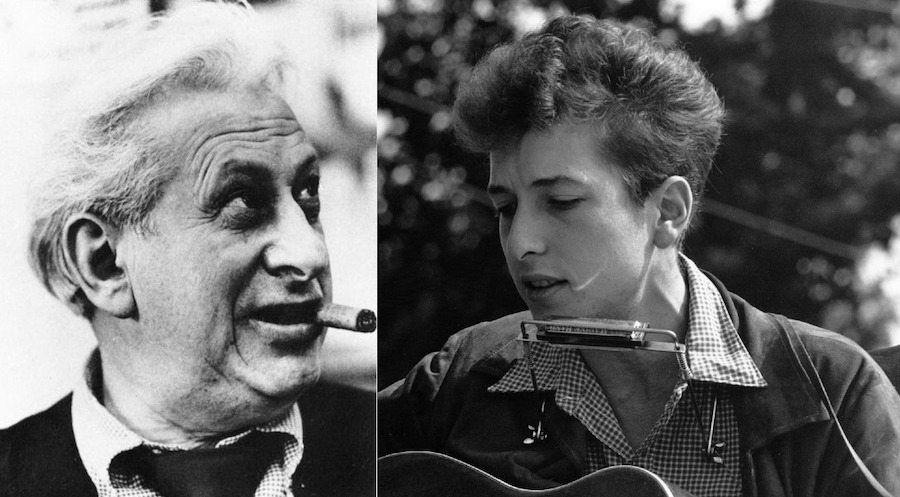

One of the most striking things about Elfstrom’s film is the way it manages, despite the constraints of the cinéma vérité form, to connect the events of Cash’s life to his music. For example, at one point Cash is walking through the barren village of Wounded Knee in South Dakota, listening to the story of the massacre of 1890 from one of the descendants of the victims, and in the next scene he is singing “Big Foot,” his song about the tragedy. The film shows Cash’s generosity toward unknown musicians. It also offers a glimpse of his close friendship with the young Bob Dylan. When Cash and Dylan got together in February of 1969 for a recording session in Nashville, Elfstrom was there. He documented the scene as the two men recorded Dylan’s “One Too Many Mornings.” Elfstrom told PBS:

John and Bob had gotten close at that point. John was saying, “Gee, I wish Bob would move down here to Tennessee. I’ve got a lot of land, and we could be neighbors!” So that was fascinating. We recorded the two of them very late at night, and they were doing a duet of one of Dylan’s songs. In the middle of the song, both John and Bob forgot the lyrics. So the recording session stopped while people scampered around the Columbia Records building trying to find the lyrics to a Bob Dylan song. When the lyrics were finally found, the two of them got together again and did some great recording. It was really an amusing session because John and Bob were teasing each other all the time.

The film was originally named Cash, and was slightly longer than the version above. In 2008 it was re-edited and renamed Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music for broadcast on PBS. It’s a revealing portrait of the country music legend, but Elfstrom allowed his subject certain areas of privacy. In particular he avoided documenting Cash’s well-known addiction to drugs. “Even back then, the powers-that-be wanted me to emphasize the substance abuse stuff, and I had to fight the entire time to stay clear of that,” said Elfstrom. “I didn’t want that pollution to confuse the message of what John was doing. I was totally willing to take John at face value, and I think he himself recognized that early on and trusted me. He was a man struggling through life like all of us, doing his best, trying to come out on top.”

Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music will be added to our collection of 500 Free Movies Online.