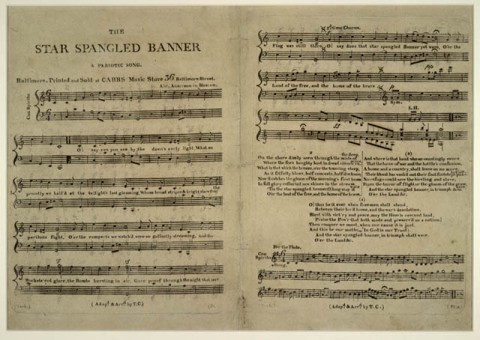

The Star-Spangled Banner became the national anthem of the United States in 1931, thanks to Herbert Hoover. And, ever since, the anthem has had its detractors. The Kennedy Center acknowledges on its website:

Some Americans complain that it celebrates war and should be reserved for military ceremonies. Others simply grumble that it is too hard to sing with a range that is out of reach for the average vocalist [anyone remember Carl Lewis giving it a try?]. Suggested replacements have included “America the Beautiful,” “God Bless America,” and “This Land is Your Land.”

And don’t forget that singers, amateur and professionals alike, often have difficulty remembering the complicated lyrics. Yes, The Star-Spangled Banner has its critics. But the great Isaac Asimov wasn’t one of them. In 1991, Asimov wrote a short piece called “All Four Stanzas” that staked out his position from the very start. It began:

I have a weakness–I am crazy, absolutely nuts, about our national anthem.

The words are difficult and the tune is almost impossible, but frequently when I’m taking a shower I sing it with as much power and emotion as I can. It shakes me up every time.

I was once asked to speak at a luncheon. Taking my life in my hands, I announced I was going to sing our national anthem–all four stanzas.

This was greeted with loud groans. One man closed the door to the kitchen, where the noise of dishes and cutlery was loud and distracting. “Thanks, Herb,” I said.

“That’s all right,” he said. “It was at the request of the kitchen staff.”

I explained the background of the anthem and then sang all four stanzas.

Let me tell you, those people had never heard it before–or had never really listened. I got a standing ovation. But it was not me; it was the anthem….

So now let me tell you how it came to be written.

And, with that, he takes you back to The War of 1812, which started 200 years ago. It’s largely a forgotten war. But it did leave us with our most enduring song. Perhaps you’ll find yourself singing it in the shower today too.