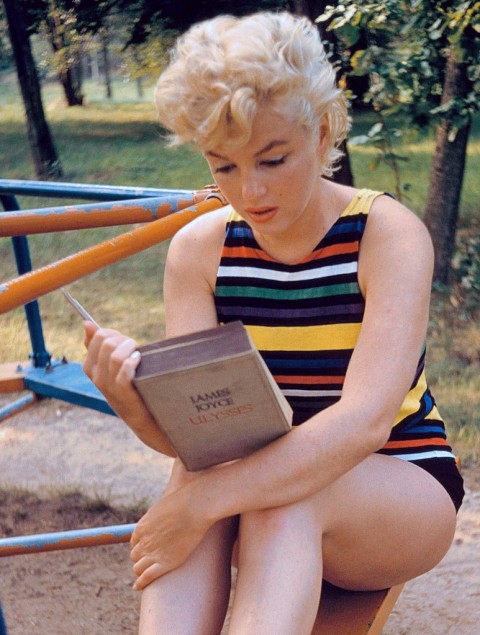

During the 1950s, the pioneering photojournalist Eve Arnold took a series of portraits of Marilyn Monroe. The now iconic photos generally present Monroe as a larger-than-life celebrity and sex symbol. Except for one. In 1955, Arnold photographed Monroe reading a worn copy of James Joyce’s modernist classic, Ulysses. It’s still debated whether this was simply an attempt to recast her image (she often played the “dumb blonde” character in her ’50s films), or whether she actually had a pensive side. (Her personal library, catalogued at the time of her death, suggests the latter.) But, either way, Arnold explained years later how this memorable photo came about:

During the 1950s, the pioneering photojournalist Eve Arnold took a series of portraits of Marilyn Monroe. The now iconic photos generally present Monroe as a larger-than-life celebrity and sex symbol. Except for one. In 1955, Arnold photographed Monroe reading a worn copy of James Joyce’s modernist classic, Ulysses. It’s still debated whether this was simply an attempt to recast her image (she often played the “dumb blonde” character in her ’50s films), or whether she actually had a pensive side. (Her personal library, catalogued at the time of her death, suggests the latter.) But, either way, Arnold explained years later how this memorable photo came about:

We worked on a beach on Long Island. She was visiting Norman Rosten the poet.… I asked her what she was reading when I went to pick her up (I was trying to get an idea of how she spent her time). She said she kept Ulysses in her car and had been reading it for a long time. She said she loved the sound of it and would read it aloud to herself to try to make sense of it — but she found it hard going. She couldn’t read it consecutively. When we stopped at a local playground to photograph she got out the book and started to read while I loaded the film. So, of course, I photographed her. It was always a collaborative effort of photographer and subject where she was concerned — but almost more her input.

You can find more images of Marilyn reading Joyce over at The Retronaut. Of course, you can download your own copy of Ulysses from our Free Ebooks collection. But we’d recommend spending time with this finely-read audio version, which otherwise appears in our list of Free Audio Books.

Related Content:

The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe’s Library: How Many Have You Read?

Stephen Fry Explains His Love for James Joyce’s Ulysses

Henri Matisse Illustrates 1935 Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses