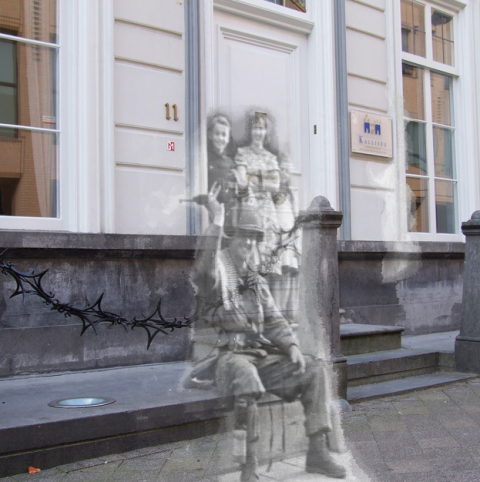

In a previous post, we brought you what is likely the only appearance on film of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle—an interview in which he talks of Sherlock Holmes and spiritualism. Although Conan Doyle created one of the most hardnosed rational characters in literature, the author himself later became converted to a variety of supernatural beliefs, and he was taken in by a few hoaxes. One such famous hoax was the case of the so-called “Cottingley Fairies.” As you can see from the photo above (from 1917), the case involved what Conan Doyle believed was photographic evidence of the existence of fairies, documented by two young Yorkshire girls, Elsie Wright and her cousin Frances Griffiths (the girl in the photo above). According to The Haunted Museum, the story of Doyle’s involvement goes something like this:

In 1920, Conan Doyle received a letter from a Spiritualist friend, Felicia Scatcherd, who informed of some photographs which proved the existence of fairies in Yorkshire. Conan Doyle asked his friend Edward Gardner to go down and investigate and Gardner soon found himself in the possession of several photos which showed very small female figures with transparent wings. The photographers had been two young girls, Elsie Wright and her cousin, Frances Griffiths. They claimed they had seen the fairies on an earlier occasion and had gone back with a camera and photographed them. They had been taken in July and September 1917, near the Yorkshire village of Cottingley.

The two cousins claimed to have seen the fairies around the “beck” (a local term for “stream”) on an almost daily basis. At the time, they claimed to have no intention of seeking fame or notoriety. Elsie had borrowed her father’s camera on a host Saturday in July 1917 to take pictures of Frances and the beck fairies.

Elsie’s father, a skeptic, filed the photos away as a joke, but her mother, Polly Wright, believed, and brought the images to Gardner (there were only two at first, not “several”), who circulated them through the British spiritualist community. When Conan Doyle saw them in 1920, he gave each girl a camera and commissioned them to take more. They produced three additional prints. The online Museum of Hoaxes details each of the five photos from the two sessions with text from Edward Gardner’s 1945 Theosophical Society publication The Cottingley Photographs and Their Sequel.

These photos swayed thousands over the course of the century, but arch-skeptic James Randi seemingly debunked them for good when he pointed out that the fairies were ringers for figures in the 1915 children’s book Princess Mary’s Gift Book, and that the prints show discrepancies in exposure times that clearly point to deliberate manipulation. The two women, Elsie and Frances, finally confessed in the early 1980s, fifty years after Conan Doyle’s involvement, that they had faked the photos with paper cutouts. Watch Randi and Elsie Wright discuss the trickery above.

The daughter and granddaughter of Griffiths possess the original prints and one of Conan Doyle’s cameras. Both once believed that the fairies were real, but as the host explains, they were not simply credulous fools. Throughout much of the twentieth century, people looked at the camera as a scientific instrument, unaware of the ease with which images could be manipulated and staged. But even as Frances admitted to the fakery of the first four photos, she insisted that number five was genuine. Everyone on the show agrees, including the host. Certainly Conan Doyle and his friend Edward Gardner thought so. In the latter’s description of #5, he wrote:

This is especially remarkable as it contains a feature quite unknown to the girls. The sheath or cocoon appearing in the middle of the grasses had not been seen by them before, and they had no idea what it was. Fairy observers of Scotland and the New Forest, however, were familiar with it and described it as a magnetic bath, woven very quickly by the fairies and used after dull weather, in the autumn especially. The interior seems to be magnetised in some manner that stimulates and pleases.

I must say, I remain seriously unconvinced. Even if I were inclined to believe in fairies, photo number five looks as phony to me as numbers one through four. But the Antiques Roadshow appearance does add a fun new layer to the story and an air of mystery I can’t help but find intriguing, as Conan Doyle did in 1920, if only for the historical angle of the three generations of Griffiths who held onto the legend and the artifacts. Oh, and the appraisal for the five original photos and Arthur Conan Doyle’s camera? Twenty-five to thirty-thousand pounds—not too shabby for an adolescent prank.

Josh Jones is a freelance writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness