Valentine’s Day draws nigh, and we can only assume our readers are desperately wondering how to declaim love poetry without looking like a total prat.

Set it to music?

Go for it, but let’s not forget the fate of that soulful young fellow on the stairs of Animal House when his sweet airs fell upon the ears of John Belushi.

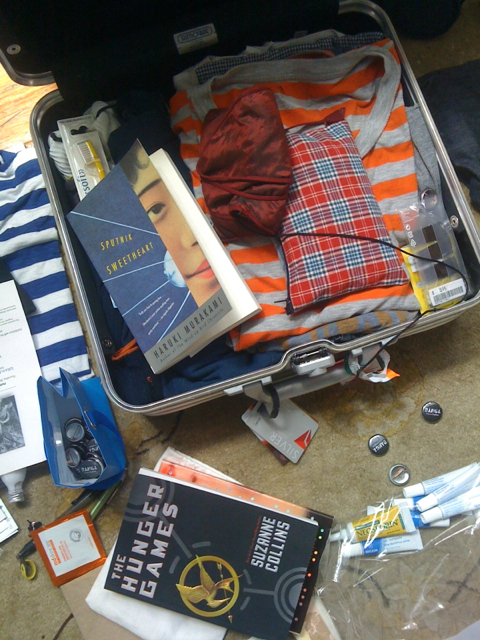

Sarah Huff, a young and relentlessly crafty blogger, hit upon a much better solution when animating E.E. Cummings’ 1952 poem [i carry your heart with me(i carry it in] for an American Literature class’ final project at Sinclair Community College.

Her construction paper cutouts are charming, but what really makes her rendering sing is the way she takes the pressure off by setting it to an entirely different love song. (Echoes of Cummings’ goat-footed balloon man in Terra Schneider’s Balloon (a.k.a. The Beginning)?)

Released from the potential perils of a too sonorous interpretation, the poet’s lines gambol playfully throughout the proceedings, spelled out in utilitarian alphabet stickers.

It’s pretty puddle-wonderful.

Watch it with your Valentine, and leave the read aloud to the punctuation-averse Cummings, below.

[i carry your heart with me(i carry it in]

i carry your heart with me(i carry it in

my heart)i am never without it(anywhere

i go you go,my dear;and whatever is done

by only me is your doing,my darling)

i fear

no fate(for you are my fate,my sweet)i want

no world(for beautiful you are my world,my true)

and it’s you are whatever a moon has always meant

and whatever a sun will always sing is you

here is the deepest secret nobody knows

(here is the root of the root and the bud of the bud

and the sky of the sky of a tree called life;which grows

higher than soul can hope or mind can hide)

and this is the wonder that’s keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart(i carry it in my heart

Related Content:

E.E. Cummings Recites ‘Anyone Lived in a Pretty How Town,’ 1953

The Mystical Poetry of Rumi Read By Tilda Swinton, Madonna, Robert Bly & Coleman Barks