Yesterday we featured Piotr Dumala’s 2000 animation of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s classic novel, Crime and Punishment, and it reminded us of many other literary works that have been wonderfully re-imagined by animators — many that we’ve featured here over the years. Rather than leaving these wondrous works buried in the archives, we’re bringing them back and putting them all on display. And what better place to start than with a foundational text — Plato’s Republic. We were tempted to show you a claymation version of the seminal philosophical work (watch here), but we decided to go instead with Orson Welles’ 1973 narration of The Cave Allegory, which features the surreal artistic work of Dick Oden.

Staying with the Greeks for another moment … This one may have Sophocles and Aeschylus spinning in their graves. Or, who knows, perhaps they would have enjoyed this bizarre twist on the Oedipus myth. Running eight minutes, Jason Wishnow’s 2004 film features vegetables in the starring roles. One of the first stop-motion films shot with a digital still camera, Oedipus took two years to make with a volunteer staff of 100. The film has since been screened at 70+ film festivals and was eventually acquired by the Sundance Channel. Separate videos show you the behind-the-scenes making of the film, plus the storyboards used during production.

Eight years before Piotr Dumala tackled Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Dumala produced a short animated film based on The Diaries of Franz Kafka. Once again, you can see his method, known as “destructive animation,” in action. It’s well worth the 16 minutes. Or you can spend time with this 2007 Japanese animation of Kafka’s cryptic tale of “A Country Doctor.” And if you’re still hankering for animated Kafka, don’t miss Orson Welles’ Narration of the Parable, “Before the Law”. The film was made by Alexander Alexeieff and Claire Parker, who using a technique called pinscreen animation, created a longer film adaptation of Nikolai Gogol’s story, “The Nose.” You can view it here.

The animated sequence above is from the 1974 film adaptation of Herman Hesse’s 1927 novel Steppenwolf. In this scene, the Harry Haller character played by Max von Sydow reads from the “Tractate on the Steppenwolf.” The visual imagery was created by Czech artist Jaroslav Bradác.

In 1999, Aleksandr Petrov won the Academy Award for Short Film (among other awards) for a film that follows the plot line of Ernest Hemingway’s classic novella, The Old Man and the Sea (1952). As noted here, Petrov’s technique involves painting pastels on glass, and he and his son painted a total of 29,000 images for this work. (For another remarkable display of their talents, also watch his adaptation of Dostoevsky’s “The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”.) The Old Man and the Sea is permanently listed in our collection of Oscar Winning Films Available Online and our collection of 700 Free Movies Online.

Italo Calvino, one of Italy’s finest postwar writers, published Italian Folktales in 1956, a series of 200 fairy tales based sometimes loosely, sometimes more strictly, on stories from a great folk tradition. Upon the collection’s publication, The New York Times named Italian Folktales one of the ten best books of the year. And more than a half century later, the stories continue to delight. Case in point: in 2007, John Turturro, the star of numerous Coen brothers and Spike Lee films, began working on Fiabe italiane, a play adapted from Calvino’s collection of fables. The animated video above features Turturro reading “The False Grandmother,” Calvino’s reworking of Little Red Riding Hood. Kevin Ruelle illustrated the clip, which was produced as part of Flypmedia’s more extensive coverage of Turturro’s adaptation. You can find another animation of a Calvino story (The Distance of the Moon) on YouTube here.

Emily Dickinson’s poetry is widely celebrated for its beauty and originality. To celebrate her birthday (it just passed us by earlier this week) we bring you this little film of her poem, “I Started Early–Took My Dog,” from the “Poetry Everywhere” series by PBS and the Poetry Foundation. The poem is animated by Maria Vasilkovsky and read by actress Blair Brown.

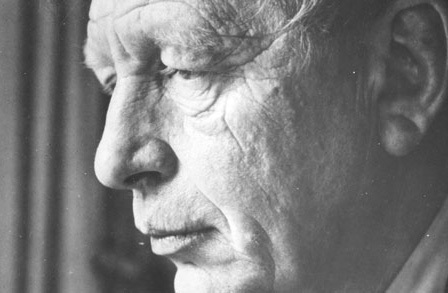

E.B. White, beloved author of Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, and the classic English writing guide The Elements of Style, died in 1985. Not long before his death, he agreed to narrate an adaptation of “The Family That Dwelt Apart,” a touching story he wrote for The New Yorker. The 1983 film was animated by the Canadian director Yvon Malette, and it received an Oscar nomination.

Shel Silverstein wrote The Giving Tree in 1964, a widely loved children’s book now translated into more than 30 languages. It’s a story about the human condition, about giving and receiving, using and getting used, neediness and greediness, although many finer points of the story are open to interpretation. Today, we’re rewinding the videotape to 1973, when Silverstein’s little book was turned into a 10 minute animated film. Silverstein narrates the story himself and also plays the harmonica.

During the Cold War, one American was held in high regard in the Soviet Union, and that was Ray Bradbury. A handful of Soviet animators demonstrated their esteem for the author by adapting his short stories. Vladimir Samsonov directed Bradbury’s Here There Be Tygers, which you can see above. And here you can see another adaptation of “There Will Come Soft Rains.”

The online bookseller Good Books created an animated mash-up of the spirits of Franz Kafka and Hunter S. Thompson. Under a bucket hat, behind aviator sunglasses, and deep into an altered mental state, our narrator feels the sudden, urgent need for a copy of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Unwilling to make the purchase in “the great river of mediocrity,” he instead makes the buy from “a bunch of rose-tinted, willfully delusional Pollyannas giving away all the money they make — every guilt-ridden cent.” The animation, created by a studio called Buck, should easily meet the aesthetic demands of any viewer in their own altered state or looking to get into one.

39 Degrees North, a Beijing motion graphics studio, started developing an unconventional Christmas card last year. And once they got going, there was no turning back. Above, we have the end result – an animated version of an uber dark Christmas poem (read text here) written by Neil Gaiman, the bestselling author of sci-fi and fantasy short stories. The poem was published in Gaiman’s collection, Smoke and Mirrors.

This collaboration between filmmaker Spike Jonze and handbag designer Olympia Le-Tan doesn’t bring a particular literary tale to life. Rather this stop motion film uses 3,000 pieces of cut felt to show famous books springing into motion in the iconic Parisian bookstore, Shakespeare and Company. It’s called Mourir Auprès de Toi.

Are there impressive literary animations that didn’t make our list? Please let us know in the comments below. We’d love to know about them.