Rochester Institute of Technology, via Wikimedia Commons

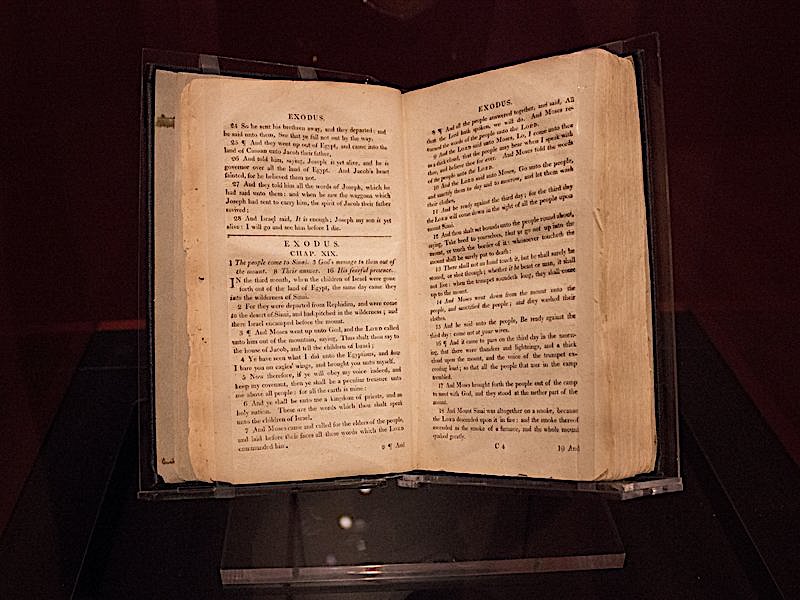

Everyone should read the Bible, and—I’d argue—should read it with a sharply critical eye and the guidance of reputable critics and historians, though this may be too much to ask for those steeped in literal belief. Yet fewer and fewer people do read it, including those who profess faith in a sect of Christianity. Even famous atheists like Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, and Melvyn Bragg have argued for teaching the Bible in schools—not in a faith-based context, obviously, but as an essential historical document, much of whose language, in the King James, at least, has made major contributions to literary culture. (Curiously—or not—atheists and agnostics tend to score far higher than believers on surveys of religious knowledge.)

There is a practical problem of separating teaching from preaching in secular schools, but the fact remains that so-called “biblical illiteracy” is a serious problem educators have sought to remedy for decades. Prominent Shakespeare scholar G.B. Harrison lamented it in the introduction to his 1964 edited edition, The Bible for Students of Literature and Art. “Today most students of literature lack this kind of education,” he wrote, “and have only the haziest knowledge of the book or of its contents, with the result that they inevitably miss much of the meaning and significance of many works of past generations. Similarly, students of art will miss some of the meaning of the pictures and sculptures of the past.”

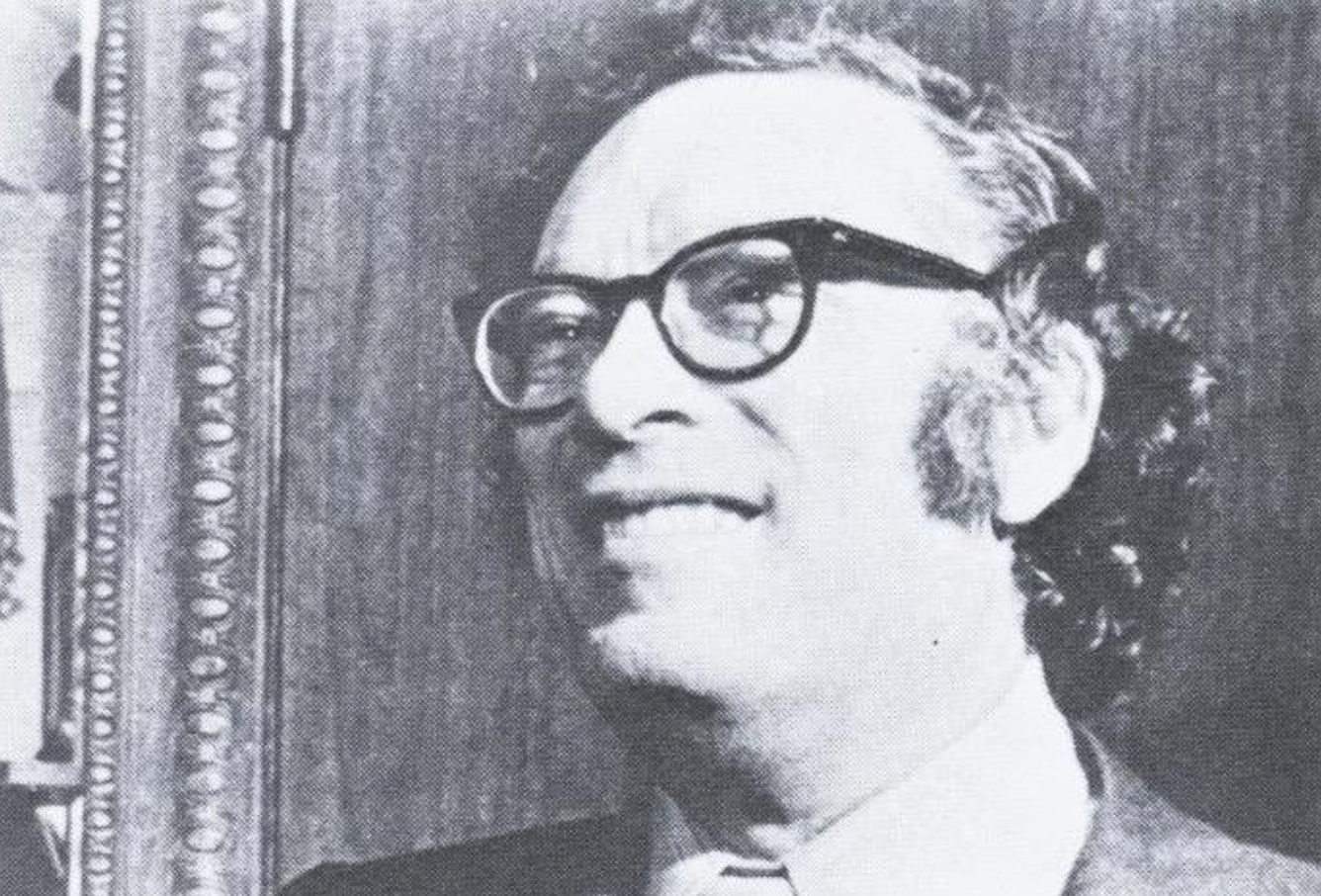

Though a devout Catholic himself, Harrison’s aim was not to proselytize but to do right by his students. His edited Bible is an excellent resource, but it’s not the only book of its kind out there. In fact, no less a luminary, and no less a critic of religion, than scientist and sci-fi giant Isaac Asimov published his own guide to the Bible, writing in his introduction:

The most influential, the most published, the most widely read book in the history of the world is the Bible. No other book has been so studied and so analyzed and it is a tribute to the complexity of the Bible and eagerness of its students that after thousands of years of study there are still endless books that can be written about it.

Of those books, the vast majority are devotional or theological in nature. “Most people who read the Bible,” Asimov writes, “do so in order to get the benefit of its ethical and spiritual teachings.” But the ancient collection of texts “has a secular side, too,” he says. It is a “history book,” though not in the sense that we think of the term, since history as an evidence-based academic discipline did not exist until relatively modern times. Ancient history included all sorts of myths, wonders, and marvels, side-by-side with legendary and apocryphal events as well as the mundane and verifiable.

Asimov’s Guide to the Bible, originally published in two volumes in 1968–69, then reprinted as one in 1981, seeks to demystify the text. It also assumes a level of familiarity that Harrison did not expect from his readers (and did not find among his students). The Bible may not be as widely-read as Asimov thought, even if sales suggest otherwise. Yet he does not expect that his readers will know “ancient history outside the Bible,” the sort of critical context necessary for understanding what its writings meant to contemporary readers, for whom the “places and people” mentioned “were well known.”

“I am trying,” Asimov writes in his introduction, “to bring in the outside world, illuminate it in terms of the Biblical story and, in return, illuminate the events of the Bible by adding to it the non-Biblical aspects of history, biography, and geography.” This describes the general methodology of critical Biblical scholars. Yet Asimov’s book has a distinct advantage over most of those written by, and for, academics. Its tone, as one reader comments, is “quick and fun, chatty, non-academic.” It’s approachable and highly readable, that is, yet still serious and erudite.

Asimov’s approach in his guide is not hostile or “anti-religious,” as another reader observes, but he was not himself friendly to religious beliefs, or superstitions, or irrational what-have-yous. In the interview above from 1988, he explains that while humans are inherently irrational creatures, he nonetheless felt a duty “to be a skeptic, to insist on evidence, to want things to make sense.” It is, he says, akin to the calling believers feel to “spread God’s word.” Part of that duty, for Asimov, included making the Bible make sense for those who appreciate how deeply embedded it is in world culture and history, but who may not be interested in just taking it on faith. Find an old copy of Asimov’s Guide to the Bible at Amazon.

Related Content:

Introduction to the Old Testament: A Free Yale Course

Christianity Through Its Scriptures: A Free Course from Harvard University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness