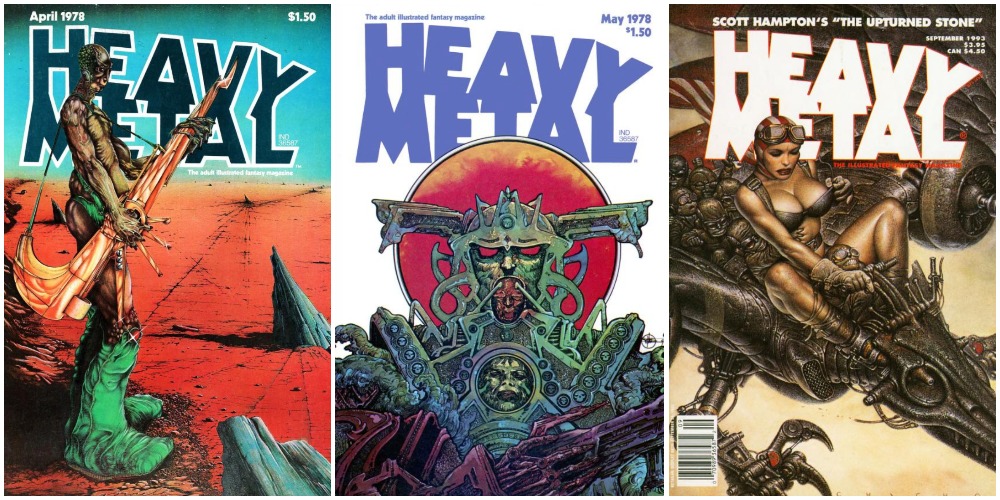

If you’ve never seen Gentlemen Broncos, the little-seen third feature by the Napoleon Dynamite-making husband-and-wife team Jared and Jerusha Hess, I highly recommend it. You must, though, enjoy the peculiar Hess sense of humor, a blend of the almost objectively detached and the heartily sophomoric fixed upon the preoccupations of deeply unfashionable sections of working-class America. In Gentlemen Broncos it makes itself felt immediately, even before the film’s story of a young aspiring science fiction writer in small-town Utah begins, with a tour de force opening credits sequence made up of homages to the pulpiest sci-fi book covers of, if not recent decades, then at least semi-recent decades.

The style of these cover images, though risible, no doubt look rich with associations to anyone who’s spent even small part of their lives reading mass-market sci-fi novels. To see more than a few higher examples, watch “The Art of Sci-Fi Book Covers,” the Nerdwriter video essay above that digs into the history of that enormously inventive yet seldom seriously considered artistic subfield.

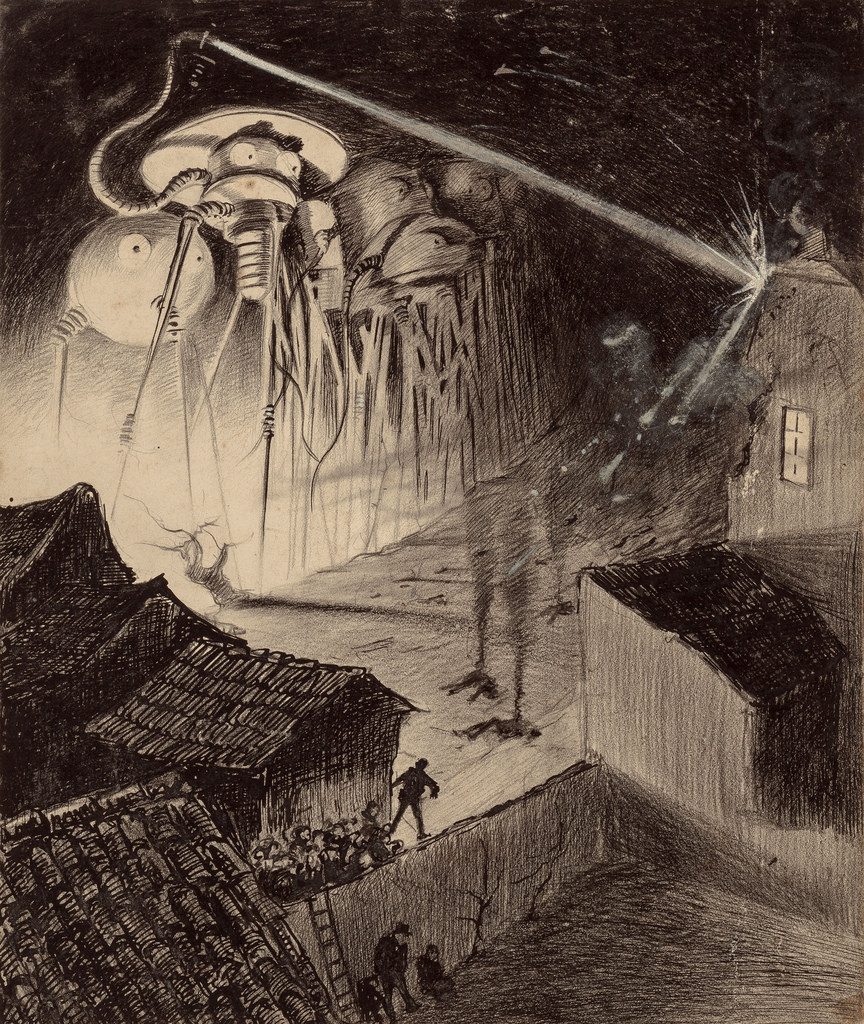

Its begins with the world’s first science-fiction magazine Amazing Stories (an online archive of which we’ve previously featured here on Open Culture) and its pieces of fantastical, eye-catching cover art by Austria-Hungary-born illustrator Frank R. Paul. In the mid-1920s, says the Nerdwriter, “these covers were probably among the strangest art that the average American ever got to see.”

It would get stranger. The Nerdwriter follows the development of sci-fi cover art from the heyday of the Paul-illustrated Amazing Stories to the introduction of mass-market paperback books in the late 1930s to Penguin’s experimentation with existing works of modern art in the 1960s to the commissioning of new, even more bizarre and evocative works by all manner of publishers (some of them sci-fi specialists) thereafter. “You can walk into any used book store anywhere and get five of these old pulp books for a dollar each,” the Nerdwriter reminds us. “And then the art is with you; it’s in your home. As you read the stories, it’s on your bedside table. It’s art you hold with your hands. It’s not precious: it’s bent, folded, and creased. And above all, it’s weird.”

Related Content:

Download 650 Soviet Book Covers, Many Sporting Wonderful Avant-Garde Designs (1917–1942)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.