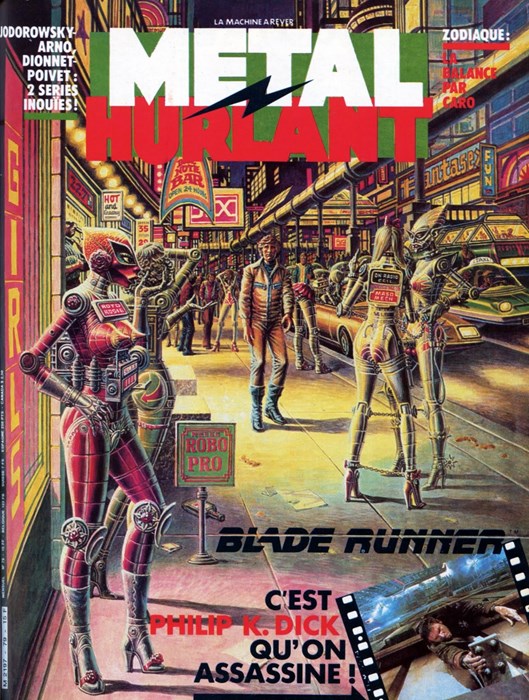

Would you believe that one particular publication inspired a range of visionary creators including Ridley Scott, George Lucas, Luc Besson, William Gibson, and Hayao Miyazaki? Moreover, would you believe that it was French, from the 1970s, and a comic book? Not that that term “comic book” does justice to Métal hurlant, which during its initial run from 1974 to 1987 not only redefined the possibilities of the medium and greatly widened the imaginative possibilities of science fiction storytelling, but brought to prominence a number of wholly unconventional and highly influential artists, chief among them Jean Giraud, best known as Moebius.

Métal hurlant, according to Tom Lennon in his history of the magazine, launched “as the flagship title of Les Humanoïdes Associés, a French publishing venture set up by Euro comic veterans Moebius, Druillet and Jean-Pierre Dionnet, together with their finance director Bernard Farkas. Influenced by both the American underground comix scene of the 1960s and the political and cultural upheavals of that decade, their goal was bold and grandiose: they were going to kick ass, take names, and make people take comics seriously.”

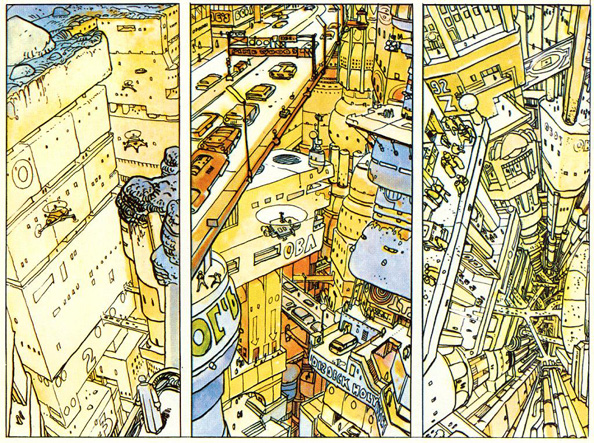

This demanded “artistic innovation at every level,” from high-quality, large-format paper stock to risk-taking storytelling “shot through with a rich vein of humour and delivered with a narrative sophistication previously unseen in the medium.”

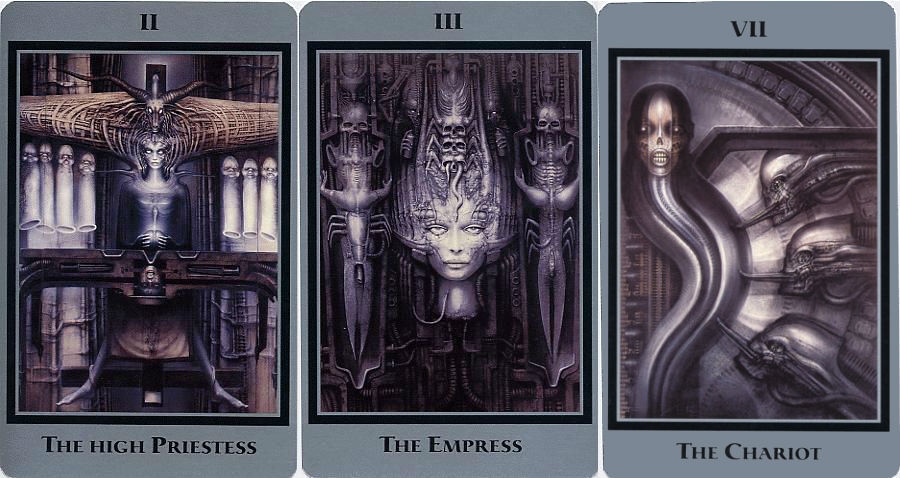

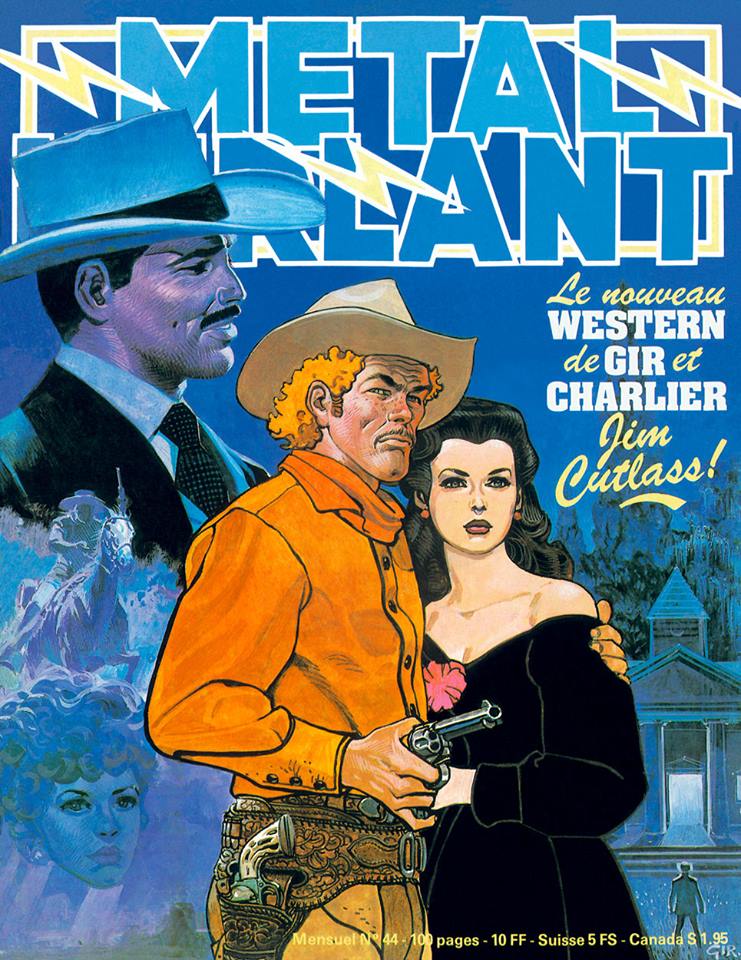

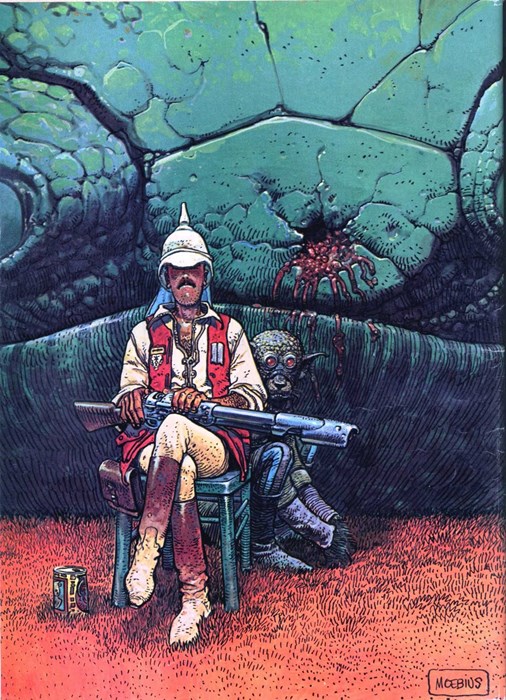

Giraud took to the possibilities of the new publication with a special avidness. Under the pen name “Gir,” writes Lennon, he “was best known as the co-creator of the popular Western series, Blueberry. By the mid-1970s, Giraud was feeling increasingly constrained by the conventions of the western genre, so decided to revive a long-dormant pseudonym to embark on more experimental work. As ‘Moebius’, Giraud not only worked in a different genre to ‘Gir’ – a deeply personal, highly idiosyncratic form of science fiction and fantasy – but his art looked like it was drawn by a completely different person,” and “unlike anything that had been seen in comics — or, for that matter, in any other medium.”

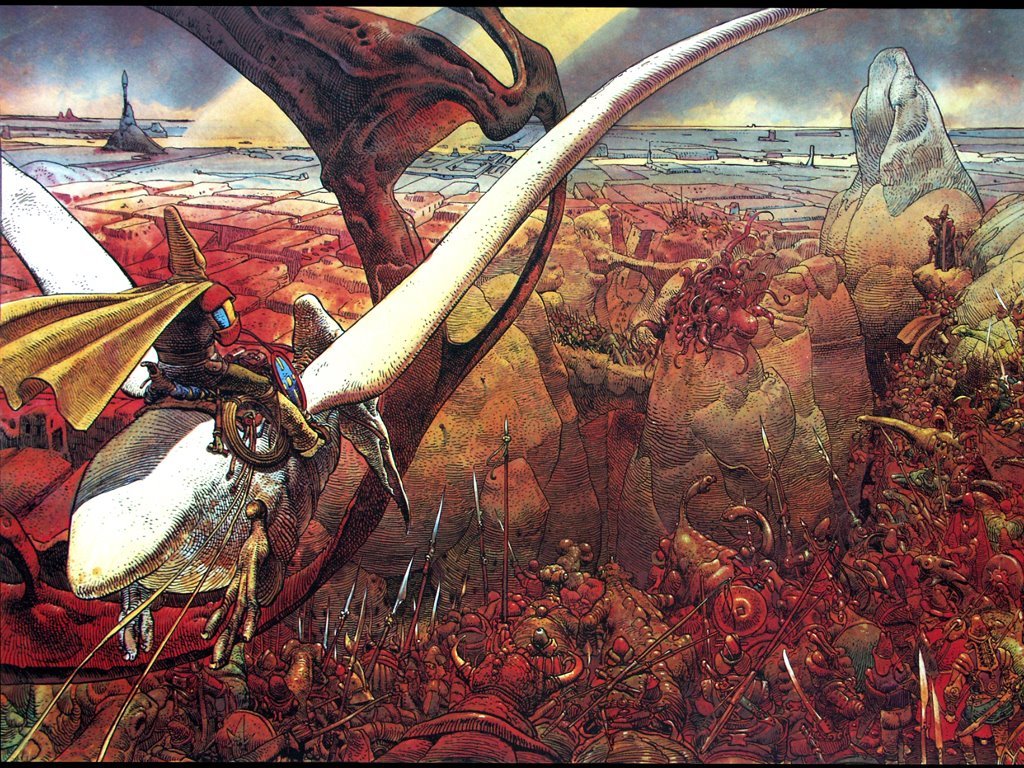

Métal hurlant saw the debuts of two of Moebius’ best-known characters: the pith-helmeted and mustachioed protector of miniature universes Major Grubert and the silent, pterodactyl-riding explorer Arzach, who bears a certain resemblance to the protagonist of Miyazaki’s 1984 film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. Read through the back issues of the magazine — or its 40-years-running American version, Heavy Metal — and you’ll also glimpse, in the work of Moebius and others, elements that would later find their way into the worlds of Neuromancer, Mad Max, Alien, Blade Runner, Star Wars, and much more besides.

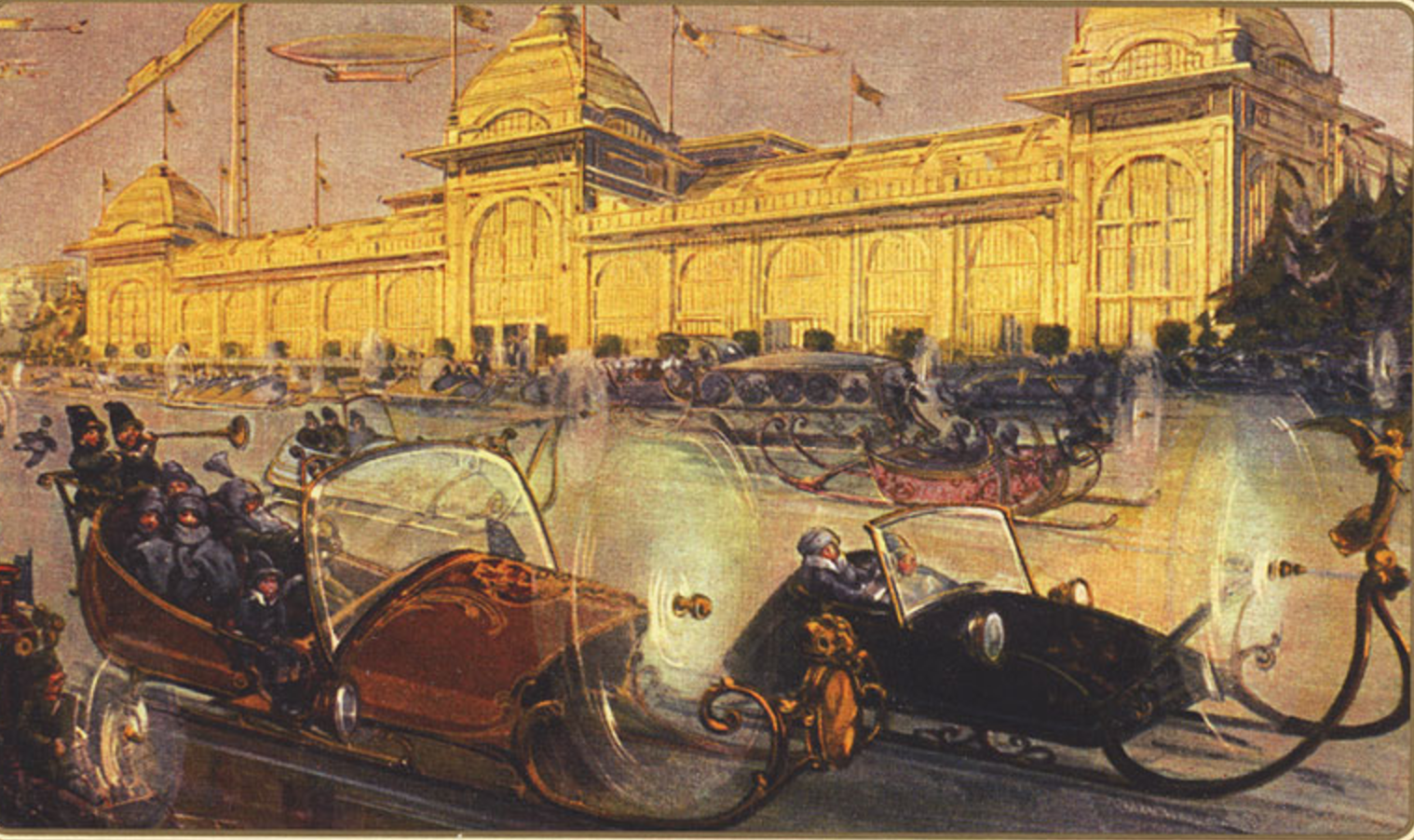

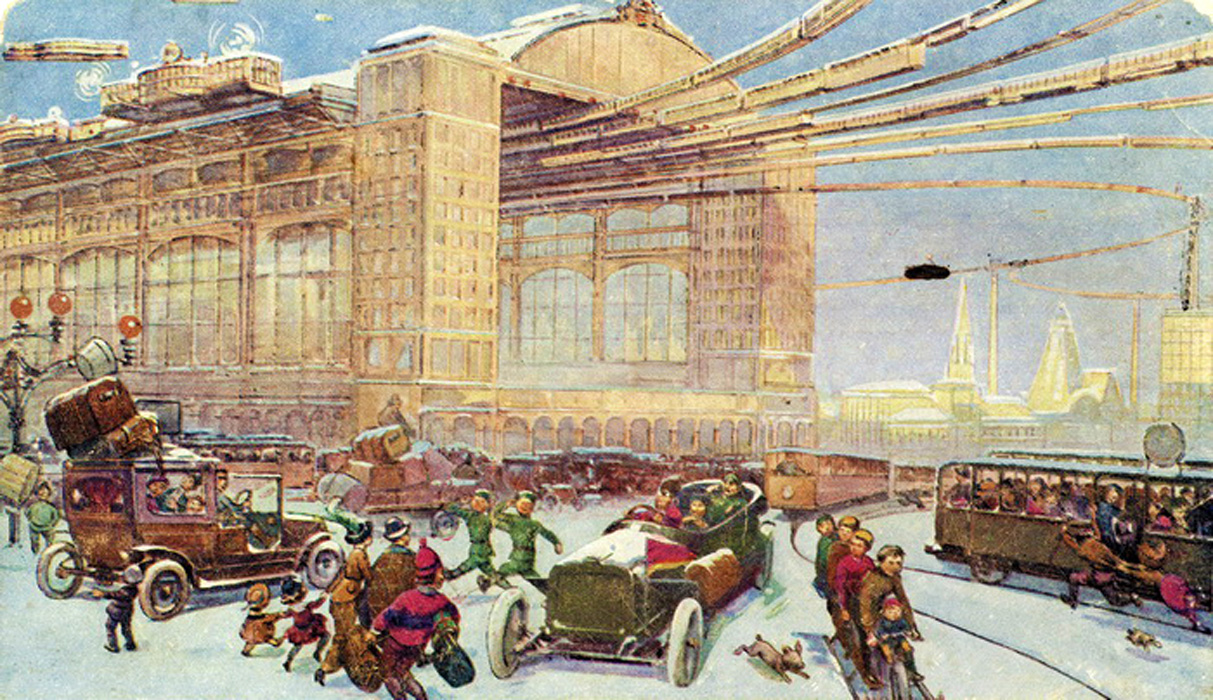

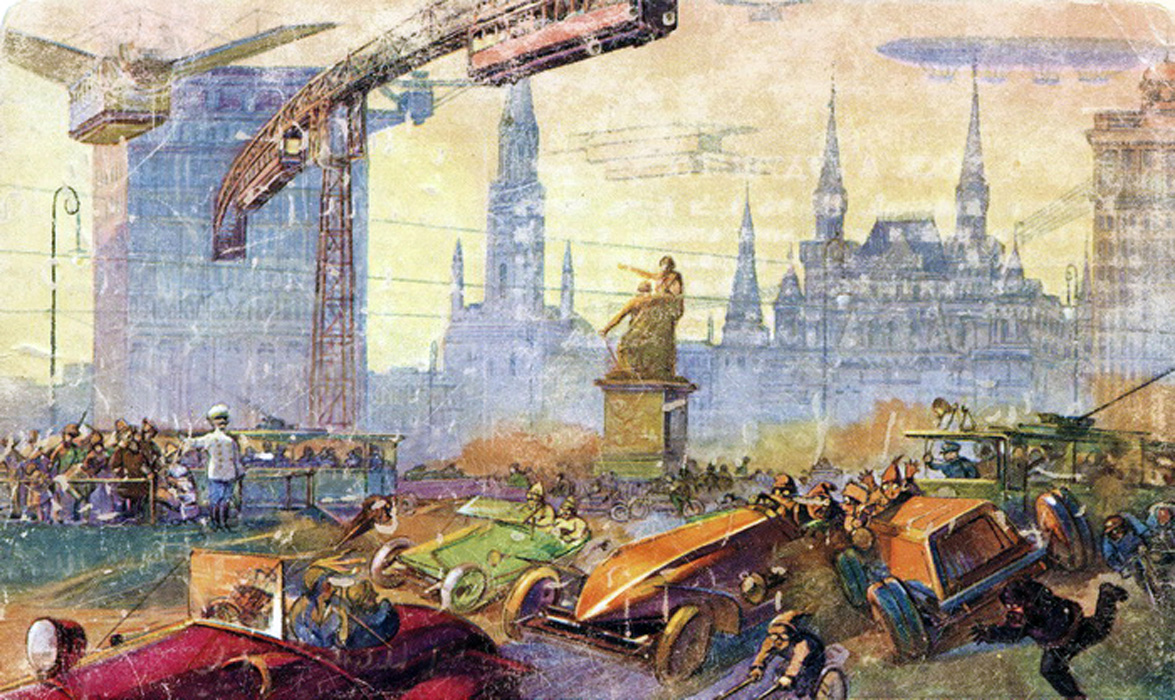

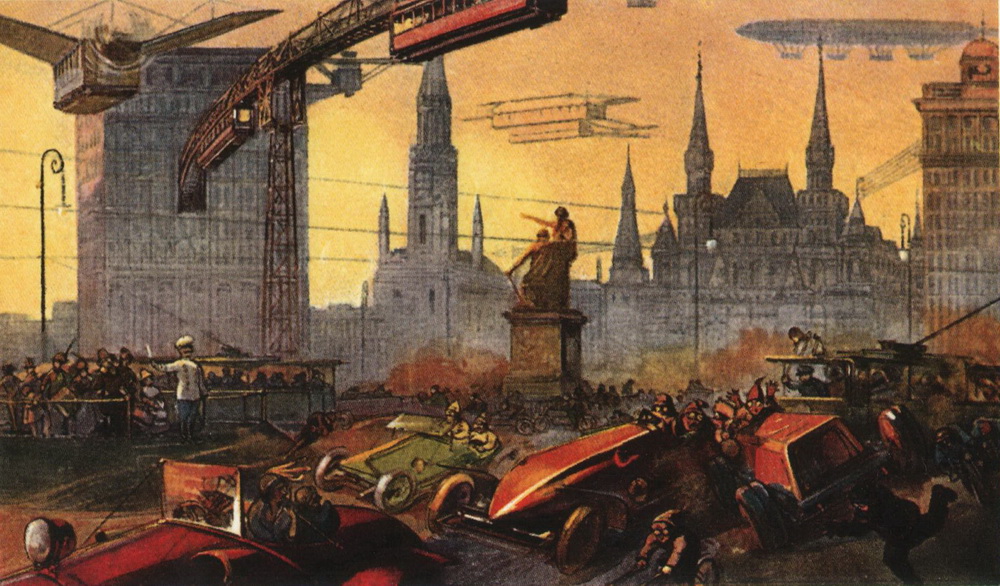

“A while ago, SF was filled with monstrous rocket ships and planets,” said Moebius in 1980. “It was a naive and materialistic vision, which confused external space with internal space, which saw the future as an extrapolation of the present. It was a victim of an illusion of a technological sort, of a progression without stopping towards a consummation of energy.” He and Métal hurlant did more than their part to transform and enrich that vision, but plenty of old perceptions still remain for their countless artistic descendants to warp beyond recognition.

via Tom Lennon/Dazed Digital

Related Content:

Moebius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

The Inscrutable Imagination of the Late Comic Artist Mœbius

Watch Moebius and Miyazaki, Two of the Most Imaginative Artists, in Conversation (2004)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.