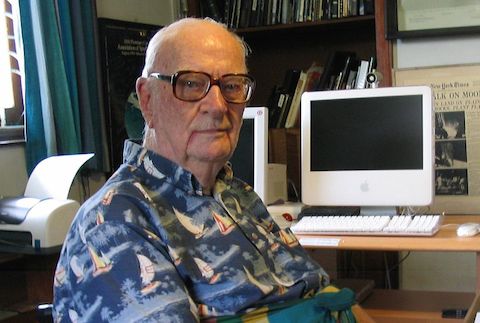

Most of Ray Bradbury’s fans think of him first as a science-fiction writer, but I think of him as a fellow Angeleno. Though born in Waukegan, Illinois, the man who would write The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451 moved with his family to Los Angeles as a teenager in 1934. Just as he used his imagination to envision the futures in which he set many of his stories, he also used it to envision the future of his adopted hometown.

“Gathering and staring is one of the great pastimes in the countries of the world,” Bradbury wrote in a 1970 article called “The Small-Town Plaza: What Life Is All About.” “But not in Los Angeles. We have forgotten how to gather. So we have forgotten how to stare. And we forgot not because we wanted to, but because, by fluke or plan, we were pushed off the familiar sidewalks or banned from the old places. Change crept up on us as we slept. We are lemmings in slow motion now, with nowhere to go.”

He lamented the fact that Los Angeles, along with most other American cities, had sacrificed its most vital gathering spaces — especially “the theater, the sweet shop, the drugstore fountain” of his childhood, and of his nostalgic novel Dandelion Wine — on the altar of the automobile. “We climb in our cars. We drive… and drive… and drive… and come home blind with exhaustion. We have seen nothing, nor have we been seen.”

Bradbury approached this grand urban planning problem, which hit its nadir in the 70s, from his then-unusual perspective of the non-driving Angeleno. Having thus never forgotten the value of the old ways, he proposes a return in the form of “a vast, dramatically planned city block” offering “a gathering place for each population nucleus” where “people would be tempted to linger, loiter, stay, rather than fly off in their chairs to already overcrowded places.”

The block would feature “a round bandstand or stage,” “a huge conversation pit [ … ] so that four hundred people can sit out under the stars drinking coffee or Cokes,” “a huge plaza walk where more hundreds might stroll at their leisure to see and be seen,” an “immense quadrangle of three dozen shops and stores,” theaters for films new and old as well as live drama and lectures, and “a coffee house for rock-folk groups.”

He described this tantalizing urban space as a proof of concept, “one to start with. Later on, one or more for each of the 80 towns in L.A.” But how to get between them? Bradbury had something of a side career advocating for a monorail system, which he summed up in a 2006 Los Angeles Times essay:

More than 40 years ago, in 1963, I attended a meeting of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors at which the Alweg Monorail company outlined a plan to construct one or more monorails crossing L.A. north, south, east and west. The company said that if it were allowed to build the system, it would give the monorails to us for free — absolutely gratis. The company would operate the system and collect the fare revenues.

It seemed a reasonable bargain to me. But at the end of a long day of discussion, the Board of Supervisors rejected Alweg Monorail.

I was stunned. I dimly saw, even at that time, the future of freeways, which would, in the end, go nowhere.

While not a single monorail line ever appeared Bradbury’s city, one did appear, three years after that faithful Board of Supervisors meeting, in François Truffaut’s adaptation of Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. You can see it in the clip at the top of the post. Notice that it seems to drop Oskar Werner and Julie Christie off in the middle of nowhere; hardly an ideal placement for a rapid-transit station, but then, the monorail itself was just a prototype, running on a test track put up at Châteauneuf-sur-Loire by its developer, the consortium SAFEGE (French Limited Company for the Study of Management and Business).

General Electric licensed SAFEGE’s monorail technology in the United States, and to promote it produced this delightfully midcentury (and no doubt Bradbury-approved) 1967 film just above. Alas, it didn’t take anywhere in the country, but you can find two still futuristic-looking SAFEGE monorails still operating in — where else? — that futuristic land known as Japan, specifically in Chiba and Fujisawa.

Los Angeles may have rejected the monorail, and it certainly has a long way to go before it matches the development of any major city in Japan, but this town has, in many ways and in many places, realized the writer’s vision of an ideal urban life. America’s 21st-century revival of city centers has begun to make theater- and coffee shop-goers, gatherers and starers, and transit-riders of us again. And not owning a car has, in Los Angeles, become almost fashionable — an idea even an imagination as capacious as Ray Bradbury’s may once have never dared to contemplate.

Related Content:

Ray Bradbury: “I Am Not Afraid of Robots. I Am Afraid of People” (1974)

Ray Bradbury: “The Things That You Love Should Be Things That You Do.” “Books Teach Us That”

Ray Bradbury: Story of a Writer 1963 Film Captures the Paradoxical Late Sci-Fi Author

Ray Bradbury: Literature is the Safety Valve of Civilization

The Secret of Life and Love, According to Ray Bradbury (1968)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.