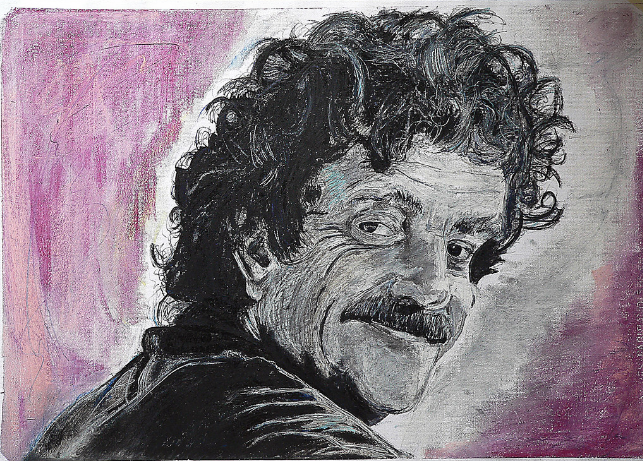

Marshall McLuhan, writes novelist and artist Douglas Coupland, entered the zeitgeist in the 1960s as “a guru or as a villain – as a harbinger of the flowering of culture, or of its death,” a “fuddy-duddy fiftysomething English lit professor from Toronto” whose distinctive research interests and even more distinctive habits of mind empowered him to come up with still-resonant insights into the modern media landscape. He knew “that the point of much of technology, TV, for instance, wasn’t the content of the shows you were watching on it. Rather, what mattered was merely the fact that you were watching TV. The act of analyzing the content of TV – or of other mediums – is either sentimental or it’s beside the point.” The medium, in other words, is the message.

That best-known of McLuhan’s prophetic one-liners (on which he expands in the ABC Radio National talk below) remains as true now as it was when it first appeared in his book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man in 1964.

Coupland emphasizes that different kinds of media, then as now, “force you to favor certain parts of your brain over others,” which we denizens of the 21st century know from intensive daily experience: “that hour you spent on Facebook came at the expense of some other way of using your brain, most likely TV viewing or book-reading, though as books and TV recede, ever more web-mediated activities will replace each other to the point where we’ll have long forgotten what the pre-electronic mind was to begin with.”

Coupland once wrote a kind of biography of McLuhan that distilled the thinker’s life, work, and current relevance into less than 250 pages, but the video at the top of the post, commissioned by Al Jazeera from animator Daniel Savage and narrated by Hong Kong activist Alex Chow, does it in just over two minutes. Chow reminds us that, even today, “if you don’t understand the medium, you don’t fully understand the message,” looking back to the invention of the printing press, and thus of mass media, and how its forms “changed our collective experience. It informed our collective identity, how we imagined ourselves.” In what McLuhan called the “electric environment,” where “everything happens at once. There’s no continuity, there’s no connection, there’s no follow-through. It’s just all now,” we will experience the end of secrecy, and with it “the end of monopolies of knowledge.”

55 years ago, McLuhan wrote that “the next medium, whatever it is – it may be the extension of consciousness – will include television as its content, not as its environment. A computer as a research and communication instrument could enhance retrieval, obsolesce mass library organization, retrieve the individual’s encyclopedic function and flip it into a private line to speedily tailored data of a salable kind.” As we’ve since discovered, these developments have both their upsides and downsides. But as Coupland writes, consider that passage seriously and “see if it doesn’t give you a chill.”

Related Content:

The Visionary Thought of Marshall McLuhan, Introduced and Demystified by Tom Wolfe

Marshall McLuhan on the Stupidest Debate in the History of Debating (1976)

McLuhan Said “The Medium Is The Message”; Two Pieces Of Media Decode the Famous Phrase

Hear Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Massage (1967)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.