J. R. R. Tolkien Writes & Speaks in Elvish, a Language He Invented for The Lord of the Rings

J. R. R. Tolkien was undoubtedly a storyteller, but he was even more of a world-builder. One may read the Lord of the Rings novels the first time for the high adventure, but one re-reads them to continue inhabiting the painstakingly crafted alternate reality of Middle-Earth. Tolkien put serious time and effort into the diversity of not just its magic, its geography, and its inhabitants, but also of its languages. Indeed, the whole of his masterwork could fairly be said to have served his linguistic interests first and foremost: “Invention of languages is the foundation,” he once wrote. “The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.”

An Oxford philologist with a special interest in Old Norse, Tolkien had been experimenting with constructed languages since adolescence. But it was The Lord of the Rings that allowed him to engage fully in that pursuit, spurring the creation of such tongues as Adûnaic, Dwarvish, and Entish. Like anyone of his linguistic expertise, he understood that, in reality, most languages come to us not in isolation but in families, and it is the family of Elvish languages — including Quendya, Exilic Quenya, Telerin, Sindarin, and Nandorin — that represents the pinnacle of his language-construction project.

In the video at the top of the post, Tolkien himself reads aloud an Elvish-language poem. Just below, you can see him writing in Elvish script, or Tengwar, one of the seven writing systems he created for The Lord of the Rings alone. He didn’t just assemble it out of forms that looked nice to him: much as with the Elvish language itself, he made sure that it plausibly descended from more basic ancestors, and that it reflected the history, social practices, and mythology of its fictional users. But nor are Elvish or Tengwar completely free of any influence from what’s spoken and written in our own world, given that Tolkien could draw on English, Old Norse, and Latin, but also Old English, Gothic, Spanish, Italian, and Greek.

Tolkien also took a strong interest in the Finnish language. In a letter to W. H. Auden, he likened it to “a complete wine-cellar filled with bottles of an amazing wine of a kind and flavor never tasted before.” The influence of Finnish manifests in certain traits of the Elvish language of Quenya — “the absence of any consonant combinations initially, the absence of the voiced stops b, d, g (except in mb, nd, ng, ld, rd, which are favored) and the fondness for the ending -inen, ‑ainen, ‑oinen” — but one suspects that Tolkien’s broader literary sensibility was shaped more by the Kalevala, the nineteenth-century national epic that inspired him to take up the study of Finnish in the first place. How close he ever got to mastery history hasn’t recorded, but as a fellow Finnish-learner, I can attest that se ei ole helppoa.

Related content:

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

Animated Video Explores the Invented Languages of Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones & Star Trek

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...

Explore Rarely-Seen Art by J. R. R. Tolkien in a New Web Site Created by the Tolkien Estate

J. R. R. Tolkien managed to write the Lord of the Rings trilogy, which ought to be accomplishment enough for one mortal. But he also wrote the The Hobbit, the gateway for generations of children into his major work, as well as a host of other works of fiction, poetry, and scholarship, many of them not published until after his death in 1973. And those are only his writings: a lifelong artist, Tolkien also produced a great many drawings and paintings, book-cover designs, and pictures meant to delight his own children as well as the children of others.

Yet somehow more material has remained in the vault, and only now brought out for proper public consideration. As reported earlier this month by Artnet’s Sarah Cascone, Tolkien’s estate “has released a new website featuring artworks, some previously unseen,” all created by the man himself.

“In addition to a number of detailed maps, the estate has released illustrations Tolkien created for The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion, as well as drawings he made for his children, landscapes drawn from real life, and imagined abstractions.”

Tolkienologists will also thrill to the new site’s “previously unpublished photographs of Tolkien and his family, including his son Christopher, who drew the final versions of the Lord of the Rings maps for publication.” (Christopher died in 2020, and Tolkien’s last surviving child Priscilla died just last month.) Divided into sections dedicated to his writing, his painting, his scholarship, his letters, his life, and related audio-visual material, this online exhibition presents Tolkien as not just a world-builder but a man in full. In his life and work, he established the model for the modern fantasy novelist, but also — as underscored by a journey across his full narrative, intellectual, and artistic range — an ideal unlikely to be equaled any time soon. Visit the site here.

Related content

110 Drawings and Paintings by J. R. R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

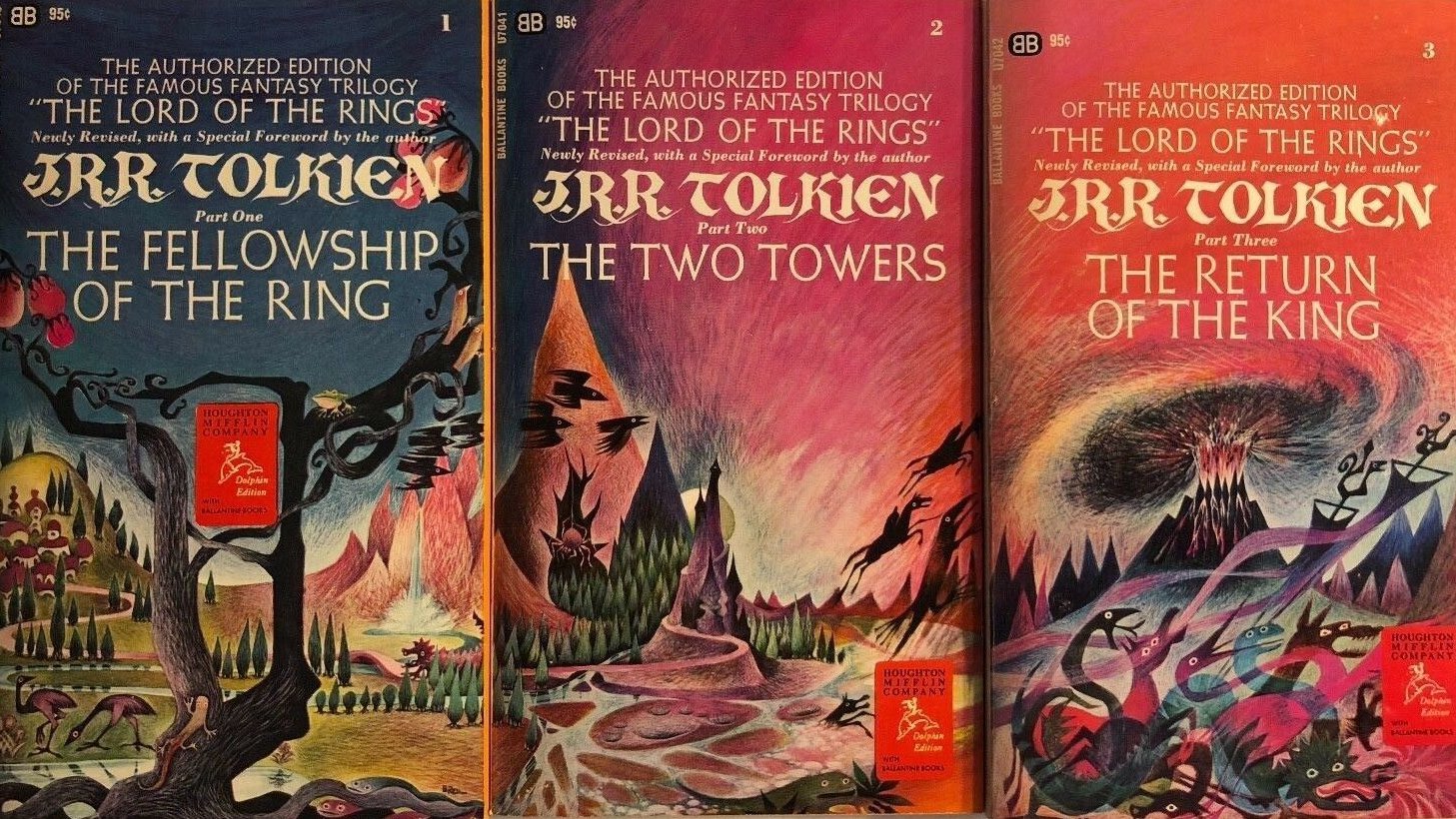

Discover J. R. R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

Discover J. R. R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...J.R.R. Tolkien Sent Illustrated Letters from Father Christmas to His Kids Every Year (1920–1943)

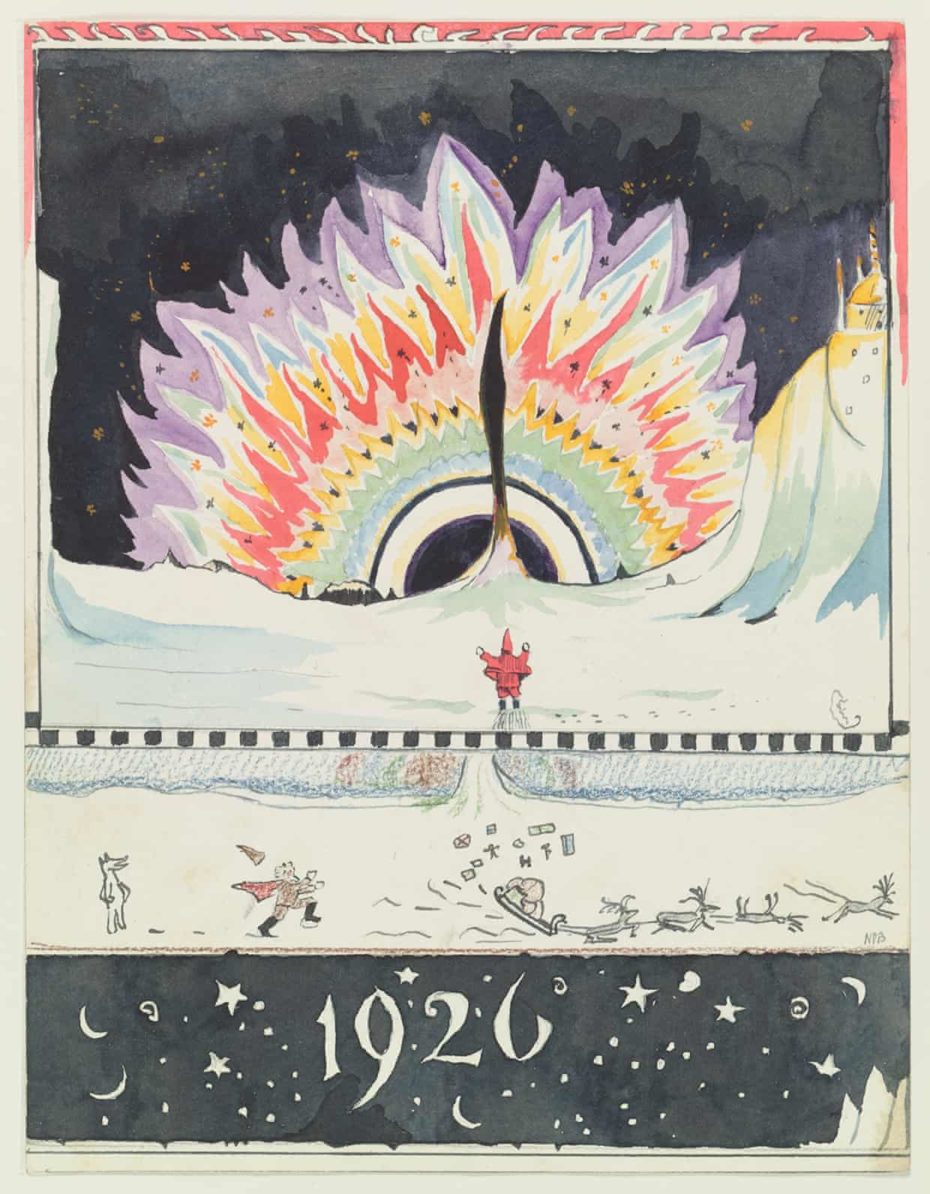

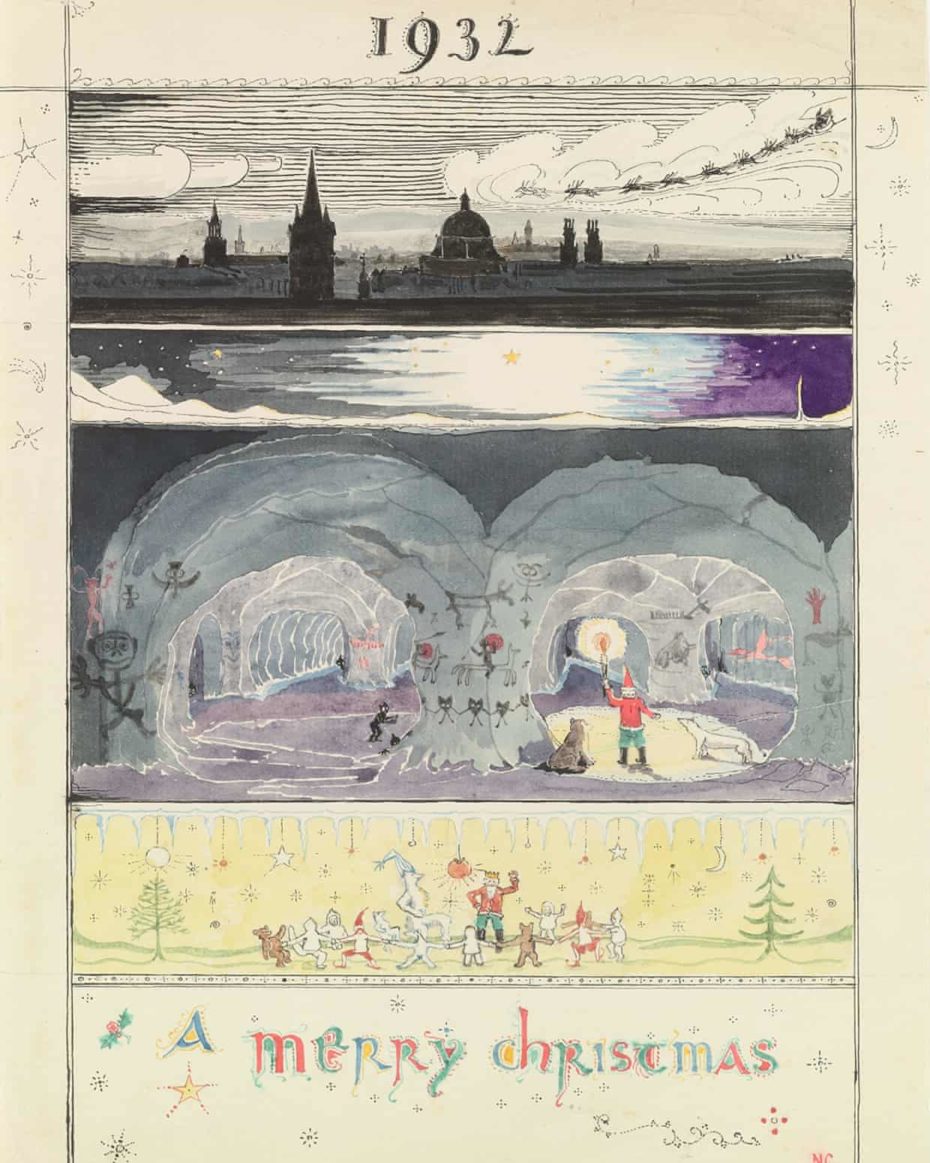

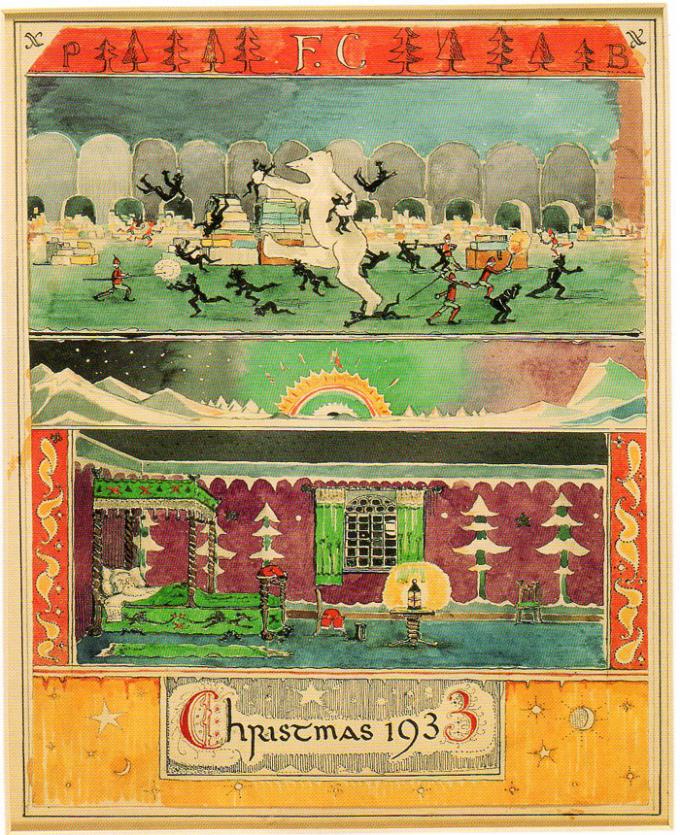

It doesn’t take children long to suspect that Santa Claus is actually their parents. But if Mom and Dad demonstrate sufficient commitment to the fantasy, so will the kids. This must have held even truer for the family of the 20th century’s most celebrated creator of fantasies, J. R. R. Tolkien. Before Tolkien had begun writing The Hobbit, let alone the Lord of the Rings trilogy, he was honing his signature storytelling and world-building skills by writing letters from Father Christmas. The toddler John Tolkien and his infant brother Michael received the first in 1920, just after their Great War veteran father was demobilized from the army and made the youngest professor at the University of Leeds. Another would come each and every Christmas until 1943, two more children and much of a life’s work later.

Every year, Tolkien’s Father Christmas had a great deal to report to John, Michael, and later Christopher and Priscilla. Apart from the usual hassle of assembling and delivering gifts, he had to contend with a host of other challenges including but not limited to attacks by marauding goblins and the accidental destruction of the moon.

The cast of characters also includes an unreliable polar-bear assistant and his cubs Paksu and Valkotukka, the sound of whose names hints at Tolkien’s interest in language and myth. Since the publication of the collected Letters From Father Christmas a few years after Tolkien’s death, enthusiasts have identified many traces of the qualities that would later emerge, fully developed, in his novels. The spirit of adventure is there, of course, but so is the humor.

Understanding seemingly from the first how to fire up a young reader’s imagination, the multitalented Tolkien accompanied each letter from Father Christmas with an illustration. Colorful and evocative, these works of art depict the scenes of both mishap and revelry described in the correspondence (itself stamped with a Tolkien-designed seal from the North Pole). How intensely must young John, Michael, Christopher, and Priscilla have anticipated these missives in the weeks — even months — leading up to Christmas. And how astonishing it must have been, upon much later reflection, to realize what attention their father had devoted to this family project. Growing up Tolkien no doubt had its downsides, as relation to any famous writer does, but unmemorable holidays can’t have been one of them.

Related Content:

Read J. R. R. Tolkien’s “Letter From Father Christmas” To His Young Children

Discover J. R .R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

The Only Drawing from Maurice Sendak’s Short-Lived Attempt to Illustrate The Hobbit

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

When Salvador Dalí Created Christmas Cards That Were Too Avant-Garde for Hallmark (1960)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...When J.R.R. Tolkien Worked for the Oxford English Dictionary and “Learned More … Than Any Other Equal Period of My Life” (1919–1920)

When J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings appeared in the mid-1950s, its first critical readers held some diverging views on the books’ quality. On the one hand, there was praise for the revival of fantasy for grown-ups, and comparisons to great epics of the past. On the other hand, Tolkien’s prose was excoriated for its wordiness, length, and seemingly inexhaustible obsession with obscurities. Both perspectives seemed to miss something important. Yes, Tolkien drew liberally from epics of the past such as the Norse Sagas and created a world as fully-realized as any in ancient mythology, building in decades what took centuries to develop.

It’s also true that Tolkien wrote in a thoroughly unusual way — unfamiliar as he was with the conventions of contemporary literary prose. But his style did not only derive from his work as a scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature. For all of the discussion of Tolkien’s encyclopedic technique, no one seemed to note at the time that the author had, in fact, invented for himself (with apologies to James Joyce) a new genre and way of writing, a kind of etymological fantasy, a kind of writing he learned while working on the Oxford English Dictionary, that august catalogue of the English language which first appeared in full in 1928 — in ten volumes after fifty years of work.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) remains an indispensable reference for scholars of language and literature, but it is not itself a typical academic text. It is a compendium, a miscellany, a descriptive map and timeline tracking how English evolves; it is the ultimate reference work, a work of philology, a discipline that had fallen out of fashion by the time of The Lord of the Rings. The first edition of the OED, begun in 1878 (five years into the proposed timeline, the editors had only reached the word “ant”), contained around 400,000 words. Between the years 1919 and 1920, Tolkien was responsible for the words between waggle and warlock. He would later say he “learned more in those two years than in any other equal period of my life.”

The OED establishes linguistic histories by citing a word’s appearances in literature and popular press over time, tracing derivations from other languages, and tracing the evolution, and extinction, of words and meanings. After his return from World War I, the future novelist found himself working under founding co-editor Henry Bradley, laboring away on words like walnut, walrus, and wampum, which “seem to have been assigned to Tolkien because of their particularly difficult etymologies,” notes the OED blog. These entries would later be singled out by Bradley as “containing ‘etymological facts or suggestion not given in other dictionaries.’ ”

The experience as an OED lexicographer prepared Tolkien for his lifelong career as a philologist. It also informed his literary technique, argue Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall, and Edmund Weiner, the authors of Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary and former OED editors, all. The authors show how Tolkien drew the language of his books directly from his etymological research. For example, “for decades it was assumed that he was being characteristically modest” when he declined to claim credit for the invention of the word “hobbit.” As it turned out, “an obscure list of mythical beings, published in 1895” came to light in 1977, including the word “ ‘hobbits’, along with such other irresistible creatures as ‘boggleboes’ and gallytrots,” writes Kelly Grovier at The Guardian.

Tolkien’s relationship to etymology in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and every other lengthy piece of writing Middle Earth-related goes far beyond digging up obscure words or coining new ones. He learned to think like a lexicographer. As the authors write, “in describing his own creative processes, Tolkien often comments on how the contemplation of an individual word can be the starting point for an adventure in imagination — and contemplating individual words is precisely what lexicographers do.” Tolkien’s boundless curiosity about the roots of language led him to “invent everything,” writes Tolkien critic John Garth, “from star mariners to calendars, flowers, cities, foodstuffs, writing systems and birthday customs, to mention just a few of the eclectic features of Middle-earth.”

Decades after Tolkien’s first association with the OED, he would become involved again with the publication in 1969 when the editor of the dictionary’s Supplement, his former student Robert Burchfield, asked for comments on the entry for “Hobbit.” Tolkien offered his own definition for just one of the many Tolkienian words that would eventually make into the OED (along with mathom, orc, mithril, and balrog). Burchfield published Tolkien’s definition almost exactly as written:

In the tales of J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973): one of an imaginary people, a small variety of the human race, that gave themselves this name (meaning ‘hole-dweller’) but were called by others halflings, since they were half the height of normal men.

Learn more about Tolkien’s work on the Oxford English Dictionary’s first edition in this article by Peter Gilliver and pick up a copy of Ring of Words here.

Related Content:

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...When the Nobel Prize Committee Rejected The Lord of the Rings: Tolkien “Has Not Measured Up to Storytelling of the Highest Quality” (1961)

When J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books appeared in the mid-1950s, they were met with very mixed reviews, an unsurprising reception given that nothing like them had been written for adult readers since Edmund Spenser’s epic 16th century English poem The Faerie Queene, perhaps. At least, this was the contention of reviewer Richard Hughes, who went on to write that “for width of imagination,” The Lord of the Rings “almost beggars parallel.”

Scottish writer Naomi Mitchison did find a comparison: to Sir Thomas Malory, author of the 15th century Le Morte d’Arthur — hardly misplaced, given Tolkien’s day job as an Oxford don of English literature, but not the sort of thing that passed for contemporary writing in the 1950s, notwithstanding the serious appreciation of writers like W.H. Auden for Tolkien’s trilogy. “No previous writer,” the poet remarked in a New York Times review, “has, to my knowledge, created an imaginary world and a feigned history in such detail.”

Auden did find fault with Tolkien’s poetry, a fact upon which critic Edmund Wilson seized in his scathing 1956 Lord of the Rings review. “Mr. Auden is apparently quite insensitive — through lack of interest in the other department,” wrote Wilson, “to the fact that Tolkien’s prose is just as bad. Prose and verse are on the same level of professorial amateurishness.” Five years later, the Nobel prize jury would make the same judgement when they excluded Tolkien’s books from consideration. Tolkien’s prose, wrote jury member Anders Österling, “has not in any way measured up to storytelling of the highest quality.”

The note was discovered recently by Swedish journalist Andreas Ekström, who delved into the Nobel archive for 1961 and found that “the jury passed over names including Lawrence Durrell, Robert Frost, Graham Green, E.M. Forster, and Tolkien to come up with their eventual winner, Yugoslavian writer Ivo Andrić,” as Alison Flood reports at The Guardian. (The Nobel archives are sealed until 50 years after the year the award is given.) Ekström has been reading through the archives “for the past five years or so,” he says, “and this was the first time I have seen Tolkien’s name among the suggested candidates.” His name appeared on the list chiefly through the machinations of his closest friend and chief supporter, C.S. Lewis.

Lewis, “also of Oxford,” Wilson sneered, “is able to top them all” in praise of Tolkien’s books. From the first appearance of his Middle Earth fantasy in The Hobbit, Lewis promised to “do all in my power to secure for Tolkien’s great book the recognition it deserves,” as he wrote in a 1953 letter to British publisher Stanley Unwin. In what might be considered an unethical promotion of his friend’s work today, Lewis responded tirelessly to critics of the trilogy, going so far, after the publication of The Two Towers, to pen an essay on the subject titled “The Dethronement of Power.” Here, Lewis explains the prolix quality of Tolkien’s prose — that which critics called “tedious” — as a narrative necessity: “I do not think he could have done it any other way.”

Tolkien’s biggest fan also urged readers to spend more time with the books and promised that the rewards would be great. In defense of the second work of the trilogy, he concluded, “the book is too original and too opulent for any final judgment on a first reading. But we know at once that it has done things to us. We are not quite the same men. And though we must ration ourselves in our rereadings, I have little doubt that the book will soon take its place among the indispensables.” And so has all of Tolkien’s work, becoming the literary standard by which high fantasy is measured, with or without a Nobel prize.

Related Content:

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...A Long-Lost Soviet Adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Resurfaces on YouTube–and Tolkien Fans Rejoice (1991)

When Peter Jackson’s The Fellowship of the Ring came out in 2001, it heralded a cinematic adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy that would, at long last, possess scale, production value, and sheer ambition enough to do justice to the original novels. This set it somewhat apart from the version of The Fellowship of the Ring that had aired just ten years before on Leningrad Television — and hasn’t been seen since, at least until its recent upload (in two parts) to Youtube. An unofficial adaptation, Khraniteli tells a story every single Tolkien reader around the world will recognize, even if they don’t understand unsubtitled Russian. The production’s appeal lies in any case not in its dialogue, but what we’ll call its look and feel.

“Featuring a score by Andrei Romanov of the rock band Akvarium and some incredibly cheap production design, no one is going to confuse this Lord of the Rings with Jackson’s films,” writes /Film’s Chris Evangelista. “The sets look like, well, sets, and the special effects — if you can call them that — are delightfully hokey. This appears to have had almost no budget, and that only lends to the charm.”

Despite its cheapness, Khraniteli displays exuberance on multiple levels, including its often-theatrical performances as well as visual effects, executed with the still-new video technology of the time, that oscillate between the hokily traditional and the nearly avant-garde. Some scenes, in fact, look not entirely dissimilar to those of Prospero’s Books, Peter Greenaway’s high-tech vision of Shakespeare that also premiered in 1991.

That year was the Soviet Union’s last, and the prolonged political shakeup that ensued could partially explain why Khraniteli went unseen for so long. Until now, obscurity-hunters have had to make do with The Fairytale Journey of Mr. Bilbo Baggins, The Hobbit (previously featured here on Open Culture), Leningrad Television’s earlier adaptation of Tolkien’s pre-Lord of the Rings children’s novel. It was the now long-gone Leningrad Television’s successor entity 5TV that just put the Soviet Fellowship of the Ring online — and in seemingly pristine condition at that — to the delight of global Tolkien enthusiasts who’d known only rumors of its existence. And as many of them have already found, for all the shortcomings, Khraniteli still has Tom Bombadil, for whose omission from his sprawling blockbusters Jackson will surely never hear the end.

Related Content:

The 1985 Soviet TV Adaptation of The Hobbit: Cheap and Yet Strangely Charming

Illustrations of The Lord of the Rings in Russian Iconography Style (1993)

Soviet-Era Illustrations Of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1976)

The Lord of the Rings Mythology Explained in 10 Minutes, in Two Illustrated Videos

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss

His were usually humorous stories, full of magic, and very often, they contained a connection to the children’s lives, because it was primarily for them that he invented them.

–Sarah Zama

The fact that “much of the inspiration of the Lord of the Rings came from [J.R.R. Tolkien’s] family,” Danielle Burgos writes at Bustle, has become an oft-repeated piece of trivia, especially thanks to such popular treatments of the author’s life as Humphrey Carter’s authorized biography, the Nicholas Hoult-starring biopic, Tolkien, and the Catherine McIlwaine-edited collection Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth. As much as Tolkien drew on his extensive knowledge of Norse, Germanic, and other mythologies and linguistic histories, and from his harrowing experiences in WWI, his career as a legendary fantasy author may never have come about without his children.

“In just one example,” notes Burgos, a collection of Tolkien’s letters shows that the character of Tom Bombadil “was based on son Michael’s wooden toy doll.” Tolkien’s oldest son John remarked before the release of the first Peter Jackson adaptation, “It’s quite incredible. When I think when we were growing up these were just stories that we were told.”

Tolkien strenuously resisted the label of children’s author; he “firmly believed,” Maria Popova points out, “that there is no such thing as writing for children.” But the degree to which his storytelling and characterization developed from his desire to entertain and educate his kids can’t be overstated in the development of his early fiction.

We see this in a small way in the little-known children’s book Mr. Bliss, written and illustrated by Tolkien sometime in the 1930s, kept in a drawer until 1957, and only published posthumously in 1982. The story itself “was inspired by his first car, which he purchased in 1932.” As evidence of its importance to the larger Tolkien canon, Popova writes, the author “went on to use two of the character names from the book, Gaffer Gamgee and Boffin, in The Lord of the Rings.” In other respects, however, Mr. Bliss is very unlike the medieval fantasies that surrounded its composition.

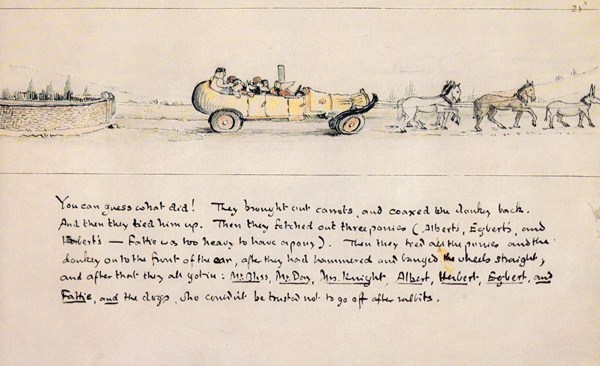

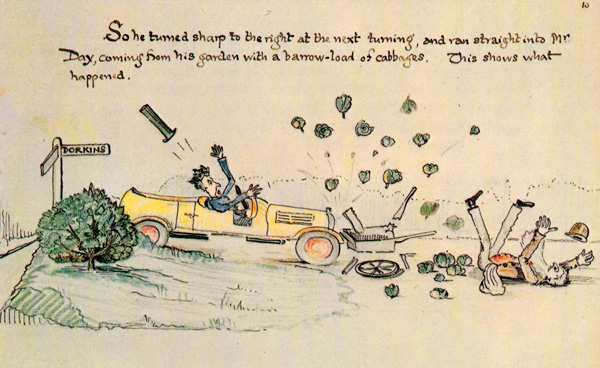

The book, affectionately handwritten and illustrated by Tolkien himself — who, also unbeknownst to many, was a dedicated artist — tells the story of Mr. Bliss, a lovable eccentric known for his exceptionally tall hats and his “girabbits,” the giraffe-headed, rabbit-bodied creatures that live in his backyard. One day, Mr. Bliss decides to buy his very first motor car[.] But his first drive en route to a friend’s house soon turns into a Rube Goldberg machine of disaster as he collides with nearly everything imaginable, then gets kidnapped by three bears.

Tolkien submitted the book for publication after the runaway success of The Hobbit created a market demand he had no particular desire to meet, telling his publisher that the story was complete. But Mr. Bliss was rejected, ostensibly because its illustrations were too expensive to reproduce. In truth, however, the public wanted more hobbits, elves, dwarves, wizards, and poetry and song in beautiful invented languages.

Tolkien would, of course, eventually deliver a “New Hobbit,” in the form of the The Lord of the Rings trilogy—books that weren’t specifically “written for his children,” Sarah Zama writes, but in which “the story he had indeed created for his children weighed heavily.” See several more Tolkien-illustrated pages from one of the trilogy’s whimsical early ancestors, Mr. Bliss, at Brain Pickings and purchase a copy of the book here.

Related Content:

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

How J.R.R. Tolkien Influenced Classic Rock & Metal: A Video Introduction

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Hear Christopher Tolkien (RIP) Read the Work of His Father J.R.R. Tolkien, Which He Tirelessly Worked to Preserve

J.R.R. Tolkien is responsible for the existence of Middle-earth, the richly realized fictional setting of the Lord of the Rings novels. But he also did his bit for the existence of the much less fictional Christopher Tolkien, his third son as well as, in J.R.R.‘s own words, his “chief critic and collaborator.” Christopher spent much of his life returning the favor, dedicating himself to the organization, preservation, and publication of his father’s notes on Middle-earth’s elaborate geography, history, and mythology until his own death this past Wednesday at the age of 95.

Most fans of Tolkien père came to know the work of Tolkien fils through The Silmarillion, the collection of the former’s previously unpublished mythopoeic writings on Middle-Earth and the universe that contains it. That book came out in 1977, four years after J.R.R. Tolkien’s death, and for a time thereafter, write The New York Times’ Katharine Q. Seelye and Alan Yuhas, “Tolkien fans and scholars wondered how much of The Silmarillion was the work of the father and how much was the work of the son.”

In response, “Christopher produced the 12-volume The History of Middle-Earth (1996), a compilation of drafts, fragments, rewrites, marginal notes and other writings culled from 70 boxes of unpublished material.”

Christopher Tolkien didn’t just take over J.R.R. Tolkien’s duties as the steward of Middle-earth; he more or less grew up in the place, and even provided comments, at his father’s request, on the work that would become The Lord of the Rings. The power of J.R.R. Tolkien’s storytelling, one often hears, owes in part to the writer’s thorough grounding in literary and linguistic subjects like English and Germanic philology, heroic verse, Old Norse, Old Icelandic, and medieval Welsh. Christopher Tolkien, in turn, made himself into what Seelye and Yhuas call “an authority, above all, on the reams of writing that his father produced.” You can hear Christopher Tolkien read authoritatively from the work of J.R.R. Tolkien in the videos presented here.

The first three clips from the top come two vinyl LPs released in 1977 and 1988 by Caedmon Records (the proto-audiobook label that also put out Edgar Allan Poe read by Vincent Price and Basil Rathbone as well as Hemingway and Faulkner read by Hemingway and Faulkner). All of their selections come from The Silmarillion, the Tolkien text that would never have seen the light of day if not for Christopher’s efforts (and those of Guy Gavriel Kay, who would later become a fantasy novelist himself). But as a tribute to the man’s life so rigorously devoted to a body of work that has fascinated so many, what could be more suitable than the video above, his reading of the very end of the final book in the Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Return of the King. Christopher Tolkien kept his father’s flame alive, and thanks to his work that flame will survive him — and generations of Tolkien readers to come.

Related Content:

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Hear J.R.R. Tolkien Read from The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit in Vintage Recordings from the Early 1950s

J.R.R. Tolkien was not a big fan of his fandom. He had serious doubts about whether any of the millions of readers who adored The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy understood anything about what he was trying to do. But none of them can be blamed, since he didn’t at first set out to write fiction at all—at least not when it came to The Lord of the Rings. The books, he said, were “an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real.”

The most famous fantasy series of all time began its life as a linguistic experiment, in other words. “The invention of languages is the foundation,” said Tolkien. “The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.” Of course, Tolkien fans know quite a bit about how personal his stories became, even as they incorporated more and more mythical elements. How could we possibly understand these stories the way Tolkien did?

Authors do not get to choose their readers, nor can they direct the interpretations of their work. Still Tolkien may have been more misunderstood than others, and maybe more entitled to complain. The scholarly work of philologists like himself—academics who studied the roots of languages and mythologies—had been mangled and misused by the Nazis. The fact caused Tolkien to confess to his son “a burning private grudge against that ruddy little ignoramus Adolf Hitler” for “ruining, perverting, misapplying, and making for ever accursed” the history Tolkien had made his life’s work. (He also penned a scathing reply to a German publisher who asked him for proof of his “Aryan” descent.)

He would also have been appalled that not long after his death, Middle Earth became a “merchandising juggernaut,” as one student of his effect on popular culture puts it. Tolkien had strenuously resisted efforts by Disney to buy the rights to his fiction, objecting to what he saw as vulgar, mercenary commercialism. The hundreds of millions of dollars poured into the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings films, and the empire of games, action figures, t‑shirts, etc., might have seemed to him the very image of power-mad wizard Saruman’s designs for world domination.

This isn’t to say we should hear Tolkien scolding us as we pick up our box set of special edition books, Blu-Rays, and LOTR tchotchkes. He was no stranger to marketing. And he produced the inspiration for some of the most beloved adaptations with his own cover art designs and over a hundred drawings and paintings of Middle Earth and its English referents. But perhaps it would repay fans of the many LOTR-themed consumables to attend to the creator of the now-self-existent world of Middle Earth every now and then—to get closer, if not to Tolkien’s intentions, then at least to his mind and voice, both recorded in his letters and his own readings from his work.

In the clips here, you can listen to Tolkien himself read from The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, including a recording at the top of him reading one of the fantasy languages he invented, then created an entire world around, the Elvish tongue Quenya in the poem “Namarie.” Some of these YouTube clips have received their own cinematic treatment, in a YouTube sort of way, like the video below with a montage of Tolkien-inspired media and a dramatic score. This may or may not be to your liking, but the origin story of the recording deserves a mention.

Shown a tape recorder by a friend, whom Tolkien had visited to pick up a manuscript of The Lord of the Rings, the author decided to sit down and record himself. Delighted with the results, he agreed to read from The Hobbit. He liked the technology enough that he continued to record himself reading from his own work. Tolkien may not have desired to see his books turned into spectacles, but as we listen to him read, it’s hard to see how anyone could resist the temptation to put his magnificent descriptions on the big screen. Hear the second part of that Hobbit reading here, and more Tolkien readings in the many links below.

Related Content:

J.R.R. Tolkien Reads From The Two Towers, the Second Book of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Hear J.R.R. Tolkien Read From The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit

J.R.R. Tolkien Snubs a German Publisher Asking for Proof of His “Aryan Descent” (1938)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch the Trailers for Tolkien and Catch-22, Two New Literary Films

For decades, fans of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings wondered if the books could ever become a film. The Beatles and John Boorman both tried to get adaptations off the ground in the 1960s and 70s, and animator Ralph Bakshi came up with his own cinematic interpretation, if only a partial one, in 1978. But now we live in a world rich with Lord of the Rings and Lord of the Rings-related material on film, thanks to the efforts of director Peter Jackson and his collaborators on not just the adaptations of The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King, but three whole feature films bringing the relatively brief tale The Hobbit to the screen.

What remains for the Tolkien-inspired filmmaker today? None, so far, have proven brave enough to take on the likes of The Silmarillion, the forbiddingly mythopoeic work published a few years after the writer’s death. But the Finnish director Dome Karukoski, whose last picture told the story of male-erotica illustrator Tom of Finland, has found material in the writer’s life.

Going by the trailer above, Tolkien deals not just with the writing of The Lord of the Rings, described by star Nicholas Hoult as “a story about journeys, the journeys we take to prove ourselves,” about “adventures” and “potent magic, magic beyond anything anyone has ever felt before.”

It’s also, says Hoult-as-Tolkien, a story about “what it means to love, and to be loved.” That fits with another apparent storyline of Tolkien itself, that of the man who dreamed up Middle-Earth’s relationship with Edith Bratt, the girl he met as a teenager who would become his wife — not long after which he received the letter summoning him to France to fight in the First World War, where he managed to survive the Battle of the Somme. An equally skilled writer of another temperament might have produced an enduring novel of the war, but Tolkien, as his generations of readers know, went in another direction entirely. A generation later, Joseph Heller proved to be that skilled writer of a different temperament, and sixteen years after coming back from the Second World War, he produced Catch-22.

Heller’s novel has also made it to the screen a few times: Mike Nichols directed a feature-film adaptation in 1970, the pilot for a television series aired three years later, and now we await a Catch-22 miniseries that will air on Hulu this May. Christopher Abbott stars as Captain John Yossarian, the hapless bombardier with no aim in the war but to stay out of harm’s way, and George Clooney (also one of the series’ directors) as Lieutenant Scheisskopf, one of the book’s cast of highly memorable minor characters. The series’ six episodes should accommodate more of that cast — and more of the forms Heller’s elaborate satire takes in the novel — than a movie can. If, as a result, you need to consult Heller’s large-format handwritten outline for the book, by all means do — and have a look at Tolkien’s annotated map of Middle-Earth while you’re at it.

Related Content:

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

Hear J.R.R. Tolkien Read From The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit

Joseph Heller’s Handwritten Outline for Catch-22, One of the Great Novels of the 20th Century

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...