Dylan Thomas’s drinking was legendary. Stories of the debauched and disheveled Welsh poet’s epic drinking binges have had a tendency to drown out serious discussion of his poetry.

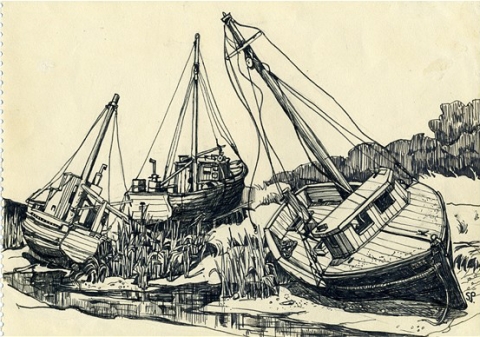

It’s a legend that Thomas helped promote, as this pencil sketch he made of himself attests. The undated self-caricature was published in Donald Friedman’s 2007 book, The Writer’s Brush: Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture by Writers. It depicts a teetering, goggle-eyed figure with tumbler in hand, happily surrounded by bottles.

Thomas would sometimes tell his friends he had cirrhosis of the liver, but his autopsy eventually disproved this. As legend has it, the poet literally drank himself to death on his American tour in the fall of 1953, when he was 39 years old. In fact, it appears Thomas may have been a victim of medical malpractice. He went to his doctor complaining of difficulty breathing. The doctor was aware of the poet’s reputation as a drinker, and had been informed by Thomas’s companion of his now-famous statement from the night before: “I’ve had 18 straight whiskies. I think that’s the record.”

So the doctor treated Thomas for alcoholism and didn’t discover he was suffering from pneumonia. He gave Thomas three injections of morphine, which can slow respiration. Thomas’s face turned blue and he went into a coma. He died four days later. When Thomas’s friends investigated, they determined he had likely consumed, at most, eight whiskies. That’s still a large amount, but the poet’s exaggeration appears to have led his doctor astray. In a sense, then, Dylan Thomas was killed not by his drinking, but by the legend of his drinking.

Related Content:

Dylan Thomas Recites ‘Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night’ and Other Poems

The Art of Sylvia Plath: Revisit Her Sketches, Self-Portraits, Drawings & Illustrated Letters

A Soft Self-Portrait of Salvador Dali, Narrated by the Great Orson Welles