The seemingly never-ending era of female artists laboring in the shadows cast by their male colleagues is coming to a close.

Ditto the tyranny of the male gaze.

Women Who Draw, a database of over 5,000 professional artists, offers a thrillingly diverse panoply of female imagery, all created, as the site’s name suggests, by artists who identify as women.

Launched by illustrators Julia Rothman and Wendy MacNaughton in response to a dismaying lack of gender parity among cover artists of a prominent magazine—in 2015, men were responsible for 92%—the site aims to channel work to female artists by boosting visibility.

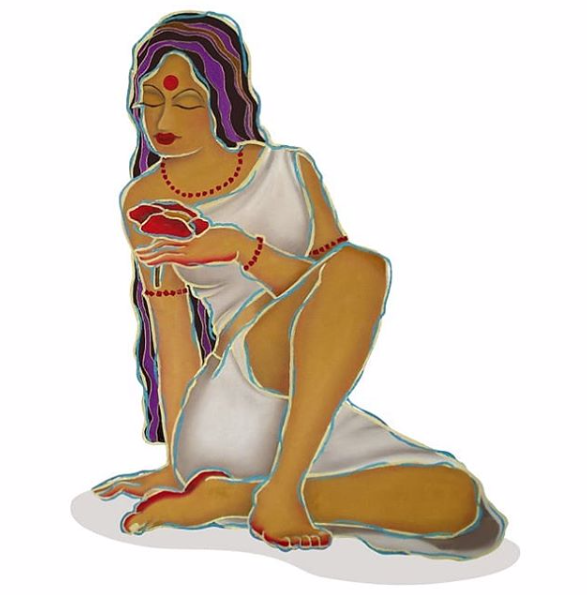

To that end, each illustrator tossing her hat in the ring is required to upload an illustration of a woman, ideally a full body view, on a white background.

The result is an astonishing range of styles, from an international cast of creators.

Not surprisingly, the majority of contributors are based on the East Coast of the United States, but given the site’s mission to promote female illustrators of color, as well as LBTQ+ and other less visible groups, expect to see growing numbers from Africa, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and Central and South America.

In addition to indicating their location, artists can checklist their religion, orientation, and ethnicity/race. (Those who would check“white” or “straight” should be prepared to accept that those categories are tabled as “WWD encourages people to seek out underrepresented groups of women.”)

Bean counting aside, the personalities of individual contributors shine through.

Some, like Paris-based American Laura Park, choose explicit self-portraiture.

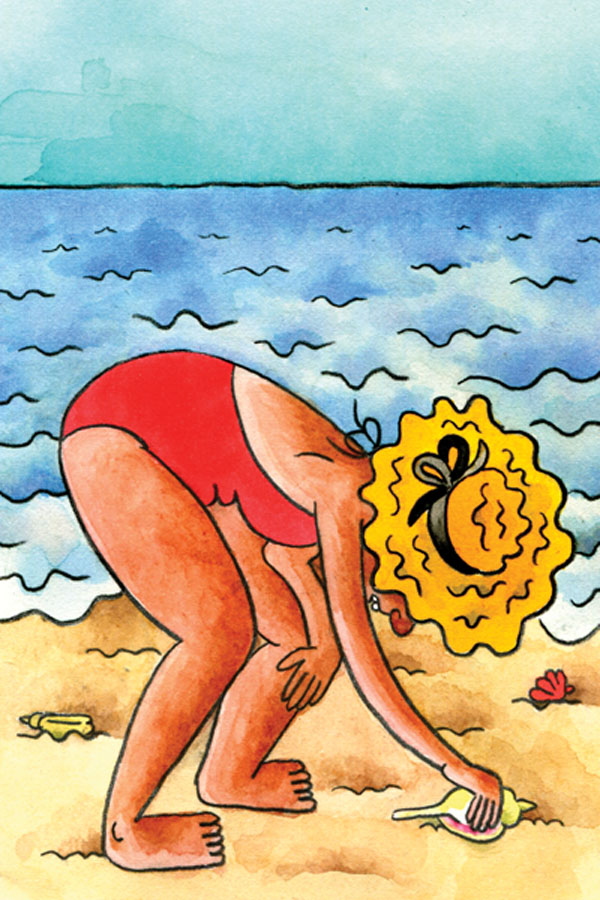

Vanessa Davis gives the lie to bikini season

SouthAsian illustrator Baani makes an impression, documenting women of her community even as she reinterprets tropes of Western art.

Pé-de-Ovo Studio corners the market on plushies.

Women Who Draw’s latest crowd-sourced project is concerned with personal stories of immigration.

Final words of encouragement from Lindsey Andrews, Assistant Art Director for the Penguin Young Readers Design Group:

Just keep putting your work out there in any form you can think of. Update your various social platforms regularly. Mail postcards of your work. Send emails. Network when you can. But, mainly, do what you love. Even if you have a portfolio full of commissioned pieces, I still like to see what you create when you get to create whatever you want. Also, let me know your process!

Related Content:

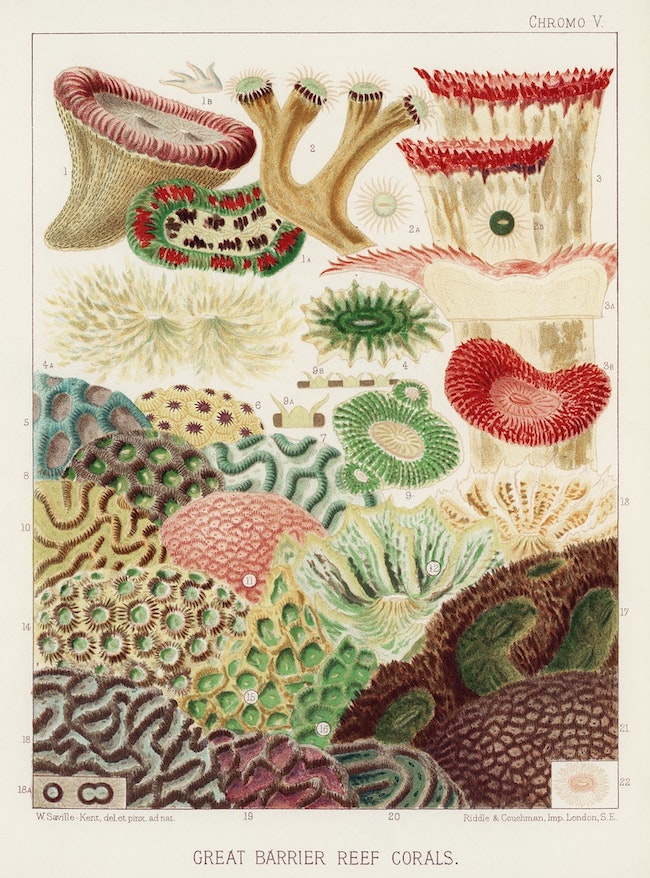

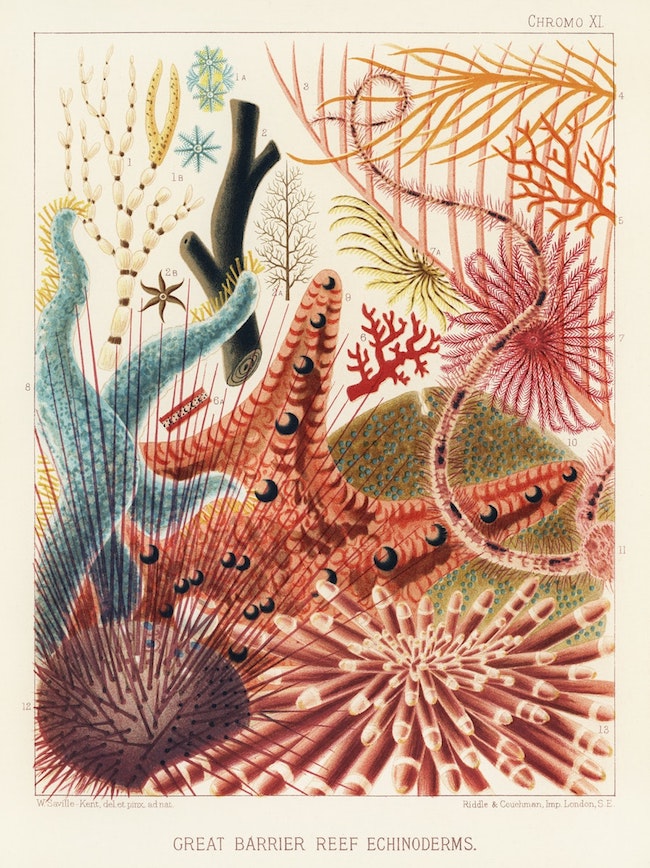

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC tonight, Monday, June 17 for another monthly installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.