Photo courtesy of MIT Museum

When I first read news of the now-infamous Google memo writer who claimed with a straight face that women are biologically unsuited to work in science and tech, I nearly choked on my cereal. A dozen examples instantly crowded to mind of women who have pioneered the very basis of our current technology while operating at an extreme disadvantage in a culture that explicitly believed they shouldn’t be there, this shouldn’t be happening, women shouldn’t be able to do a “man’s job!”

The memo, as Megan Molteni and Adam Rogers write at Wired, “is a species of discourse peculiar to politically polarized times: cherry-picking scientific evidence to support a pre-existing point of view.” Its specious evolutionary psychology pretends to objectivity even as it ignores reality. As Mulder would say, the truth is out there, if you care to look, and you don’t need to dig through classified FBI files. Just, well, Google it. No, not the pseudoscience, but the careers of women in STEM without whom we might not have such a thing as Google.

Women like Margaret Hamilton, who, beginning in 1961, helped NASA “develop the Apollo program’s guidance system” that took U.S. astronauts to the moon, as Maia Weinstock reports at MIT News. “For her work during this period, Hamilton has been credited with popularizing the concept of software engineering.” Robert McMillan put it best in a 2015 profile of Hamilton:

It might surprise today’s software makers that one of the founding fathers of their boys’ club was, in fact, a mother—and that should give them pause as they consider why the gender inequality of the Mad Men era persists to this day.

Hamilton was indeed a mother in her twenties with a degree in mathematics, working as a programmer at MIT and supporting her husband through Harvard Law, after which she planned to go to graduate school. “But the Apollo space program came along” and contracted with NASA to fulfill John F. Kennedy’s famous promise made that same year to land on the moon before the decade’s end—and before the Soviets did. NASA accomplished that goal thanks to Hamilton and her team.

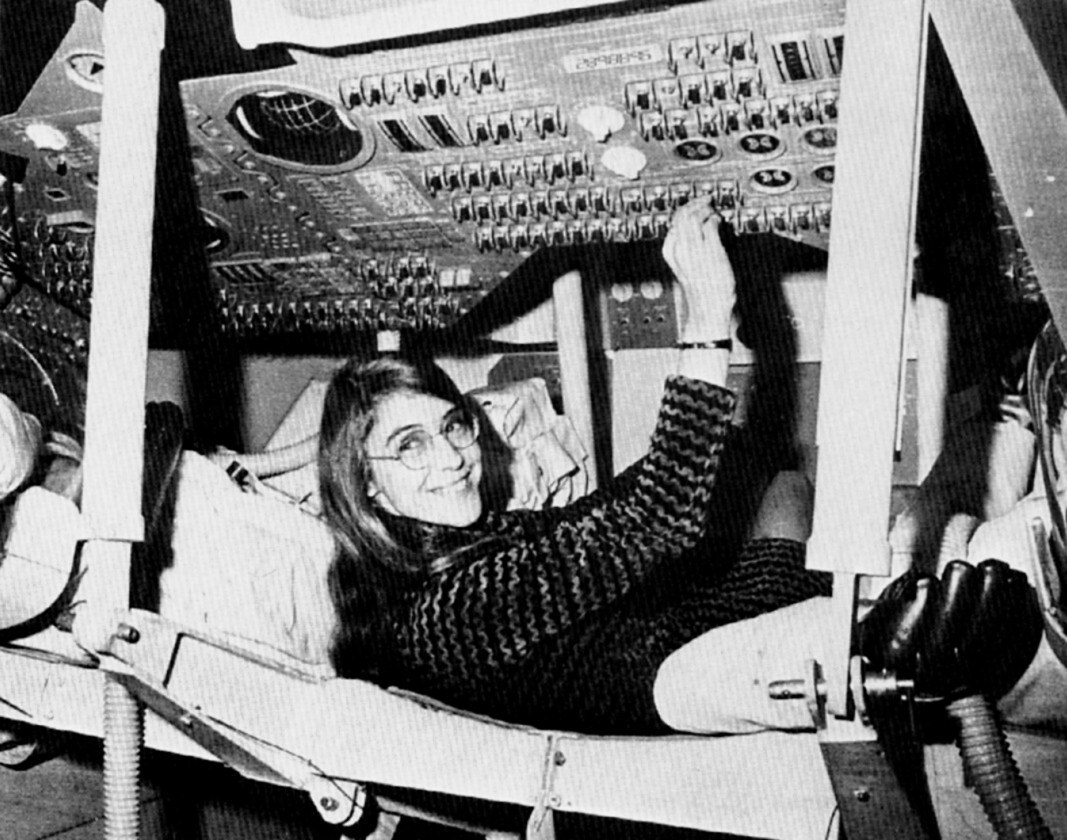

Photo courtesy of MIT Museum

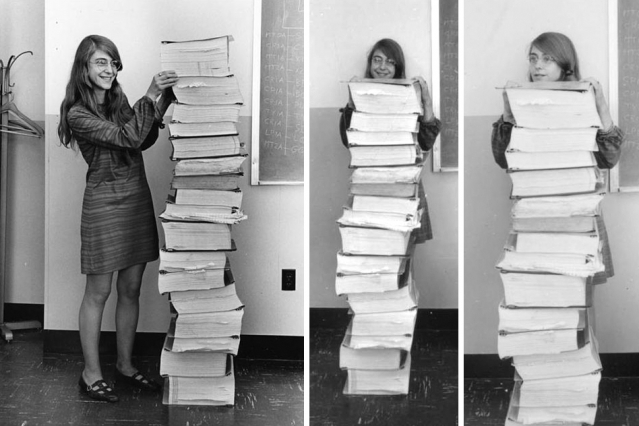

Like many women crucial to the U.S. space program (many doubly marginalized by race and gender), Hamilton might have been lost to public consciousness were it not for a popular rediscovery. “In recent years,” notes Weinstock, “a striking photo of Hamilton and her team’s Apollo code has made the rounds on social media.” You can see that photo at the top of the post, taken in 1969 by a photographer for the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory. Used to promote the lab’s work on Apollo, the original caption read, in part, “Here, Margaret is shown standing beside listings of the software developed by her and the team she was in charge of, the LM [lunar module] and CM [command module] on-board flight software team.”

As Hank Green tells it in his condensed history above, Hamilton “rose through the ranks to become head of the Apollo Software development team.” Her focus on errors—how to prevent them and course correct when they arise—“saved Apollo 11 from having to abort the mission” of landing Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon’s surface. McMillan explains that “as Hamilton and her colleagues were programming the Apollo spacecraft, they were also hatching what would become a $400 billion industry.” At Futurism, you can read a fascinating interview with Hamilton, in which she describes how she first learned to code, what her work for NASA was like, and what exactly was in those books stacked as high as she was tall. As a woman, she may have been an outlier in her field, but that fact is much better explained by the Occam’s razor of prejudice than by anything having to do with evolutionary determinism.

Note: You can now find Hamilton’s code on Github.

Related Content:

NASA Puts Its Software Online & Makes It Free to Download

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness