I think we’ve all had moments when, bellying up to our favorite sushi bar, we’ve watched the chef in action behind the counter and thought, “I wonder if I could do that?” Then we see a documentary like Jiro Dreams of Sushi and think, “Well, no, I probably couldn’t do that.” Still, you don’t have to live, breathe, and dream sushi yourself to get something out of practicing the craft, and if you want to get a handle on its basics right now, you could do much worse than watching the video series Diaries of a Master Sushi Chef.

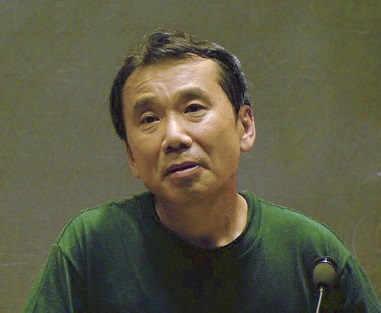

Hiroyuki Terada, the master sushi chef in question, first learned the basics himself at home from his father, then continued his studies in Kōchi, on the Japanese island of Shikoku, then made a name for himself in America, at NoVe Kitchen and Bar in Miami.

More recently, his fame has come from his Youtube channel, which, in line with his reputation for coming up with unconventional dishes, features videos like this conversion of a Big Mac into a sushi roll — kids, don’t try this at home. But do watch some of his instructional videos, which cover such traditional topics as how to prepare sushi rice, knife skills, and how to fillet a whole salmon.

If you really want to start from square one, Terada has also put together a four-part miniseries on making sushi at home from grocery store ingredients. When you get those teachings down, you have only to practice — and practice, and practice, and practice some more. From there, you can also move on to Terada’s roll-specific videos, which teach how to make some of his more elaborate creations: the crazy salmon roll, the uni tempura monster roll, even something called the meat lover’s roll. Would Jiro approve? Maybe not, but the Miami nightlife crowd certainly seems to.

Related Content:

The Right and Wrong Way to Eat Sushi: A Primer

How to Make Instant Ramen Compliments of Japanese Animation Director Hayao Miyazaki

Cookpad, the Largest Recipe Site in Japan, Launches New Site in English

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.