In the mid-1930s, some beautiful, high-quality books were published by a company called Limited Editions Club, which, according to Antiques Roadshow appraiser Ken Sanders, was “famous for re-issuing classics of literature and commissioning contemporary living artists to illustrate 1500-copy signed limited editions.” One of those books—the 1934 Pablo Picasso-illustrated edition of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata—is, next to Henri Matisse’s 1935 edition of Joyce’s Ulysses, one of “the most sought after and desirable limited editions on the market today.”

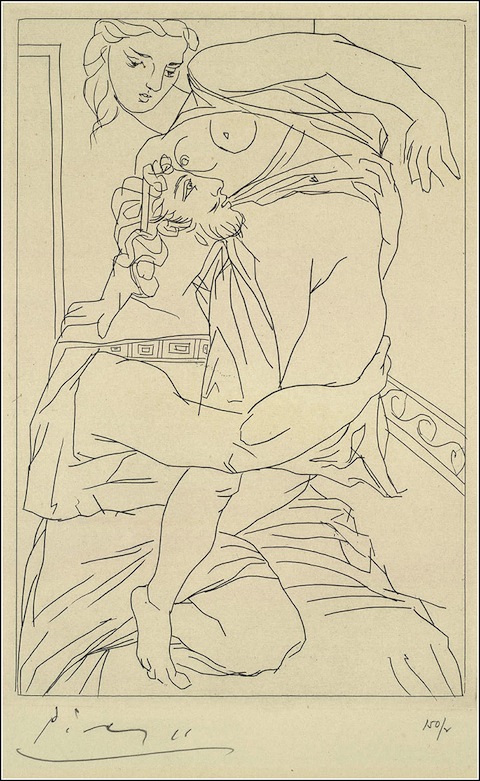

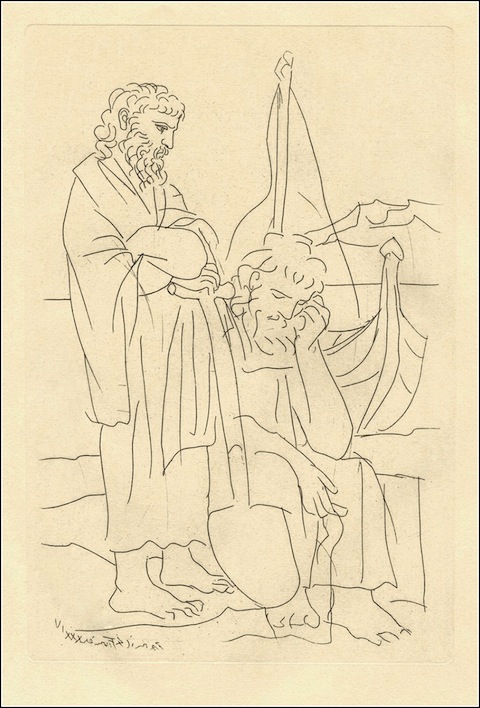

The book’s rarity, of course, renders it more valuable on the market than a mass-produced object, but whether it was worth $5,000 or $50, I think I’d hold onto my copy if I had one (here’s one for $12,000 if you’re buying). While Aubrey Beardsley’s 1896 illustrations do full and stylish justice to the satirical Greek comedy’s bawdy nature, Picasso’s drawings render several scenes as tender, softly sensual tableaux. The almost childlike simplicity of these illustrations of a play about female power and the limits of patriarchy do not seem like the work of a rumored misogynist, but then again, neither do any of Picasso’s other domestic scenes in this spare, rounded style of his.

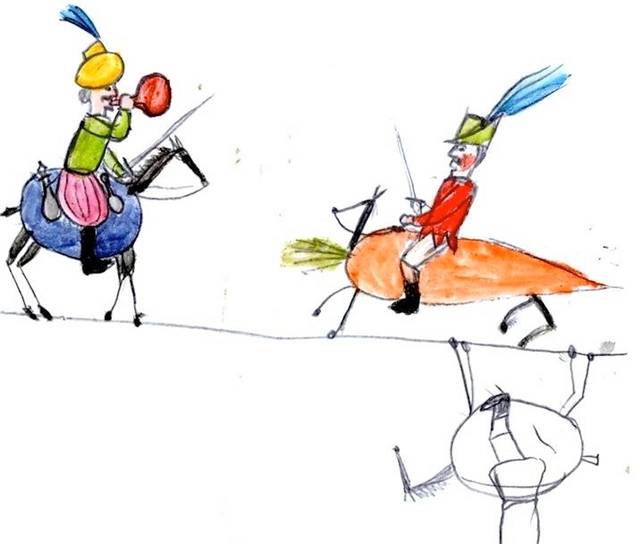

In Aristophanes’ play, the women of Greece refuse their husbands sex until the men agree to end the Peloponnesian War. The play makes much of the men’s mounting sexual frustration, with several humorous gestures toward its physical manifestations. Beardsley’s drawings offend Victorian eyes by making these scenes into exaggerated nudist farce. Picasso’s modernist sketches all but ignore the overt sexuality of the play, picturing two lovers (2nd from top) almost in the posture of mother and child, the pent up men (image above) as dejected and downcast gentle souls, and the reunion of the sexes (below) as a highly stylized, none too erotic, feast. These images are three of six signed proofs featured on the blog Book Graphics. See their site to view all six illustrations.

Related Content:

Henri Matisse Illustrates 1935 Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness