Full disclosure: I love George Saunders. Can I say that? Can I say that George Saunders rekindled my faith in contemporary fiction? Is that too fawning? Obsequious, but true! Oh, how bored I had become with fourth-hand derivative Carver, cheapened Cheever, sometimes the sad approximations of Chuck Palahniuk. So boring. It had gotten so all I could read was Philip K. Dick, over and over and over. And Alice Walker. And Wuthering Heights. And Thomas Hardy. Do you see the pass I’d come to? Then Saunders. In a writing class I took, with one of Gordon Lish’s acolytes (no names), I read Saunders. I read Wells Towers, Padgett Powell, Aimee Bender—a host of modern writers who were doing something new, in short, sometimes very short, forms, but explosive!

What is it about George Saunders that grips? He has mastered frivolity, turned it into an art of diamond-like compression. And for this, he gets a MacArthur Fellowship? Well, yes. Because what he does is brilliant, in its shockingly unaffected observations of humanity. George Saunders is an accomplished writer who puts little store in his accomplishments. Instead, he values kindness most of all, and generosity. These are the qualities he extols, in his typically droll manner, in a graduation speech he delivered to the 2013 graduating class at Syracuse University. Kindness: a little virtue, you might say. The New York Times has published his speech, and I urge you to read it in full. I’m going to give you half, below, and challenge you to find George Saunders wanting.

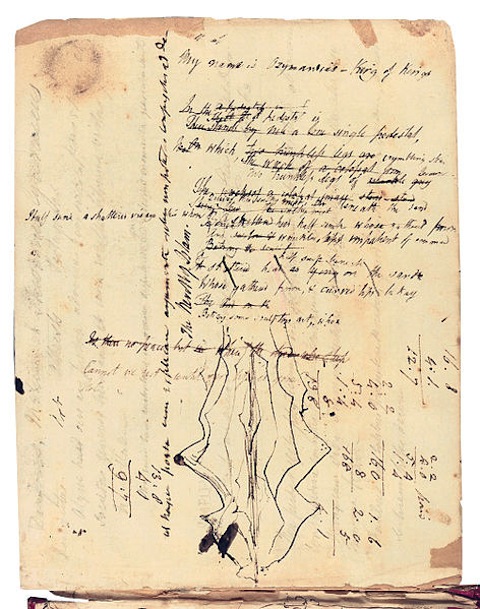

Down through the ages, a traditional form has evolved for this type of speech, which is: Some old fart, his best years behind him, who, over the course of his life, has made a series of dreadful mistakes (that would be me), gives heartfelt advice to a group of shining, energetic young people, with all of their best years ahead of them (that would be you).

And I intend to respect that tradition.

Now, one useful thing you can do with an old person, in addition to borrowing money from them, or asking them to do one of their old-time “dances,” so you can watch, while laughing, is ask: “Looking back, what do you regret?” And they’ll tell you. Sometimes, as you know, they’ll tell you even if you haven’t asked. Sometimes, even when you’ve specifically requested they not tell you, they’ll tell you.

So: What do I regret? Being poor from time to time? Not really. Working terrible jobs, like “knuckle-puller in a slaughterhouse?” (And don’t even ASK what that entails.) No. I don’t regret that. Skinny-dipping in a river in Sumatra, a little buzzed, and looking up and seeing like 300 monkeys sitting on a pipeline, pooping down into the river, the river in which I was swimming, with my mouth open, naked? And getting deathly ill afterwards, and staying sick for the next seven months? Not so much. Do I regret the occasional humiliation? Like once, playing hockey in front of a big crowd, including this girl I really liked, I somehow managed, while falling and emitting this weird whooping noise, to score on my own goalie, while also sending my stick flying into the crowd, nearly hitting that girl? No. I don’t even regret that.

But here’s something I do regret:

In seventh grade, this new kid joined our class. In the interest of confidentiality, her Convocation Speech name will be “ELLEN.” ELLEN was small, shy. She wore these blue cat’s‑eye glasses that, at the time, only old ladies wore. When nervous, which was pretty much always, she had a habit of taking a strand of hair into her mouth and chewing on it.

So she came to our school and our neighborhood, and was mostly ignored, occasionally teased (“Your hair taste good?” – that sort of thing). I could see this hurt her. I still remember the way she’d look after such an insult: eyes cast down, a little gut-kicked, as if, having just been reminded of her place in things, she was trying, as much as possible, to disappear. After awhile she’d drift away, hair-strand still in her mouth. At home, I imagined, after school, her mother would say, you know: “How was your day, sweetie?” and she’d say, “Oh, fine.” And her mother would say, “Making any friends?” and she’d go, “Sure, lots.”

Sometimes I’d see her hanging around alone in her front yard, as if afraid to leave it.

And then – they moved. That was it. No tragedy, no big final hazing.

One day she was there, next day she wasn’t.

End of story.

Now, why do I regret that? Why, forty-two years later, am I still thinking about it? Relative to most of the other kids, I was actually pretty nice to her. I never said an unkind word to her. In fact, I sometimes even (mildly) defended her.

But still. It bothers me. So here’s something I know to be true, although it’s a little corny, and I don’t quite know what to do with it:

What I regret most in my life are failures of kindness.

Those moments when another human being was there, in front of me, suffering, and I responded…sensibly. Reservedly. Mildly.

Or, to look at it from the other end of the telescope: Who, in your life, do you remember most fondly, with the most undeniable feelings of warmth?

Those who were kindest to you, I bet.

It’s a little facile, maybe, and certainly hard to implement, but I’d say, as a goal in life, you could do worse than: Try to be kinder.

Read the rest of Saunders’ speech here, and be moved. Try not to be.

Related Content:

Oprah Winfrey’s Harvard Commencement Speech: Failure is Just Part of Moving Through Life

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness